Sergei Rachmaninoff

Somberness and melancholia afflicted this brilliant musician all of his life, and for a few of his closest friends and family members, Sergei Rachmaninoff was ever seen smiling or heard laughing. Whereas, his domestic life seemed to have been remarkably satisfactory, his letters and recorded conversations are gloomy, and he found his best working condition a dispirited state. He wore an unrelenting mask of depression and solitude throughout his entire life, a guise unwilling to openly reveal his warmth and sensitivity, but only through his greatest works was he able to achieve this, launching him into a life of failures and successes. Sergei Rachmaninoff became a brilliant composer, conductor, and a touring virtuoso of the pianoforte that received world-wide acclaim.

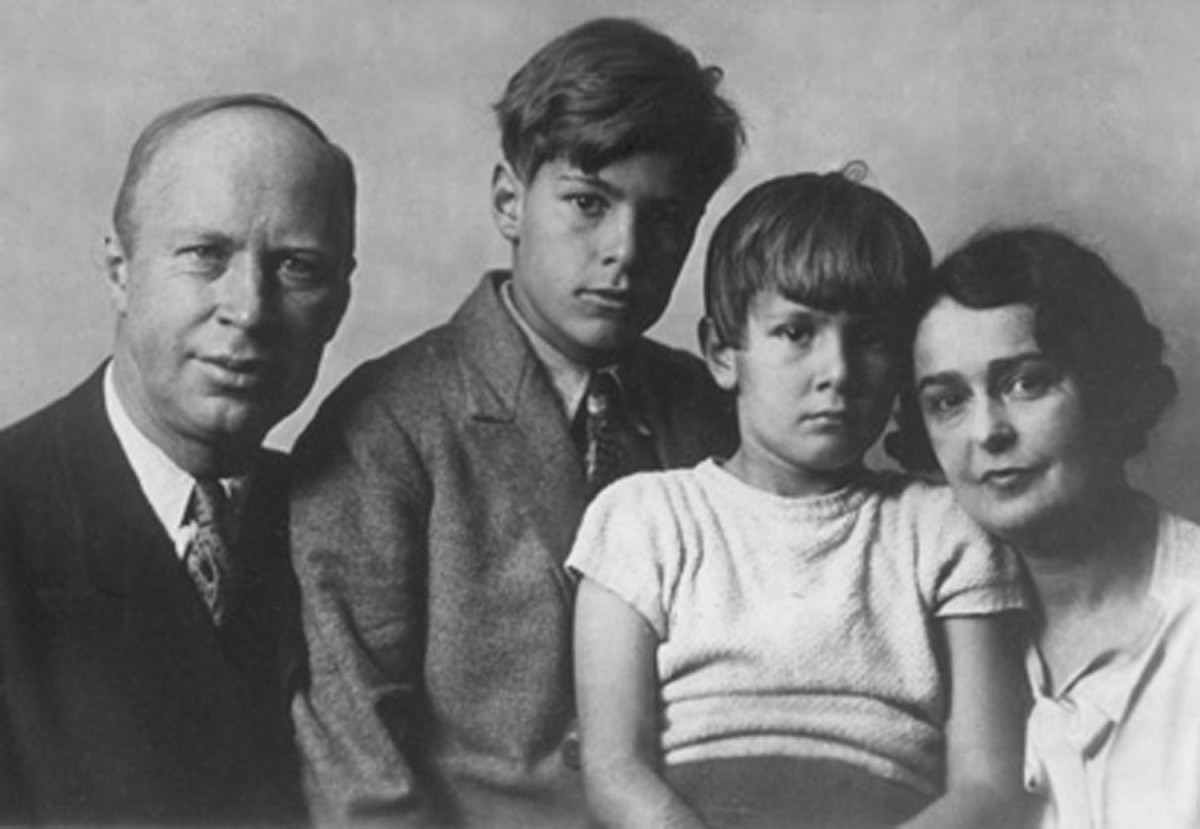

Sergei Rachmaninoff was born in Oneg, Russia on April 2, 1873, and one of six children between Vaily Rachmaninoff and Lubov Boutakova. Little is known of Sergei’s parents because he seldom said much of them, especially his mother, nor is there any reference to them in his letters or in any articles relating to him; however, the lack of information and Sergei’s unwillingness to discuss them was not without cause. His father, Vaily Rachmaninoff, had the reputation of being a featherbrained fellow always pursuing women who consequently abandoned his family before his children were grown. His mother, Lubov Boutakova, was considered very stern and strict, who often punished her children and tried to organize their lives. Nonetheless, quite the opposite of Sergei’s mother, his father was always seen as a kind and caring father toward his children often spoiling them, and with reason, Vaily was the preferred parent in the Rachmaninoff’s home (Seroff p.5).

Sergei Rachmaninoff’s life was not easy during his childhood years. His father’s extravagance and ultimate desertion took a toll on his mother, who never recovered from it. Because of these events, it created an unhappy atmosphere in the home and subjected Sergei to sometimes cruel punishments; Sergei was once seen placed under the piano for a long period of time as the result of his mother’s punishment. Vaily Rachmaninoff’s abandonment left the family financially ruined forcing them to move from Oneg to St. Petersburg after their estate was sold at a public auction. However, this marked the beginning of a new life for the Rachmaninoffs, not only because of the change from country to city but also because of the incompatibility of Sergei’s parents; however, the lack of supervision left Sergei Rachmaninoff to naturally wander into the streets were he was often seen at the skating rink (Seroff p. 7-8).

Sergei’s Rachmaninoff’s childhood years showed little inclination to music. As the favorite grandson of Grandmother Boutakova, who saw to most of the expenses, Rachmaninoff spent his childhood years living irresponsibly happy. It was not until he was 12 years old that two events left him a deep impression belonging to this period of his life. His sister Elena, who was five years his senior, made the most profound and beautiful musical impressions. She was gifted with a beautiful and glorious voice and it was through her that Rachmaninoff was introduced to Tchaikovsky’s music. The second impression came to Rachmaninoff from his grandmother, who was a very devout woman, taking him to every service at various churches and cathedrals all over the city. The toiling of the bells and the beauty of the singing by the best choirs in St. Petersburg proved to be an inspiration from which Sergei Rachmaninoff was to draw for the rest of his life.

However, Rachmaninoff was perceived as a lazy and mischievous boy and his talent was not above average. At the insistence of his mother and her appeals to her nephew, Alexander Siloti, a rising star among pianists, a young and tearful Rachmaninoff left Moscow to be trained by Zverev, Alexander’s former teacher. Hence, Rachmaninoff’s independent life had begun, one which offered him little happiness and much pain (Seroff p. 9-11).

Tutelage under Zverev was harsh and agonizing during the years that Rachmaninoff lived with him, which was until the age of sixteen. Nevertheless, Zverev’s strict, severe, and many times abusive teachings contradicted another side of his nature; he took no money from the poor and talented pupils, was very kind and thoughtful toward his protégés, and protected them by forbidding them to go boating, skating, or horseback riding because he feared for their hands.

Zverev’s demand of absolute obedience taught Rachmaninoff many skills; one was the correct positioning of the hands over the piano so that the further development of technical ability would not be hampered by stiffness of wrist or arm. It was said that Zverev was successful in the fundamentals. The upper grades professors, who had their own methods, were always happy to work with Zverev’s students when Zverev eventually turned over his pupils for further instruction. The pupils came to them with the fundamentals and corrected placement of the hands preventing the need to start from the beginning. Moreover, Zverev possessed a kind of intuitive talent, the power to awaken in his pupils such a love of music and an interest to solve the problems they encountered, and his teachings could not be considered anything but successful (Seroff p. 12-14).

Zverev induced Rachmaninoff to enter the Moscow Conservatory, where he became a brilliant student. However, at the age of sixteen, the friendship that developed over the four years of his stay ended in a bitter quarrel. The quarrel was said to be due to Rachmaninoff’s growing independence and Zverev’s unrelenting control at a request the young composer made, but it was later rumored that Rachmaninoff left Zverev’s home because he disapproved of Zverev’s homosexuality; nonetheless, he kept it a secret for the sake of the teacher’s reputation.

Rachmaninoff had walked into Zverev’s life a spoiled and mischievous child and walked-out looking an “old” sixteen year-old. Even in his youthful face, Sergei Rachmaninoff was old-looking, with deep creases that lent an expression of disappointment and disapproval, and although he had a warm and kind nature, his demeanor kept people at a distance. Those who knew Rachmaninoff during his adolescence noted a resemblance to Zverev himself, not only in his features, but in his manner as well (Seroff p. 35).

Rachmaninoff did not return to St. Petersburg after he left Zverev’s house, but remained in Moscow with relatives where he continued in the Moscow Conservatory. In 1891 when Rachmaninoff was only eighteen, he won the highest honors for piano playing, and in 1892 he was awarded the gold Medal of Honor for composition. His first important work was the Piano Concerto no. 1 in F-sharp minor, op. 1; the following year Rachmaninoff graduated from the conservatory a year ahead of his class. Part of his task for the final exam was the composition of a short opera, his one-act opera, Aleko in which he wrote in a few weeks. Aleko, based on Pushkin’s poem The Gypsies, was produced in Moscow the following year with considerable success. Thus by the age of twenty, Sergei Rachmaninoff became one of the most promising figures in Russian music circles. It was at this moment that he had the remarkable fortune to compose the most famous piano piece of modern times, the C-sharp minor Prelude. This Prelude evoked the sound of tolling church bells, one device he frequently used thereafter. The popularity of his work began with a performance by Siloti in London, and spread to every corner of the music world. (Ewen p.315; Sabaneyeff p. 103; Teachout par. 10).

Sergei Rachmaninoff began to work on his First symphony in D minor, and in 1897 came its premier under brilliant auspices when Glazunov conducted it in St. Petersburg. If Rachmaninoff was to have his first humiliating and humbling experience, it was during this performance. To the young composer’s amazement, the orchestra played appallingly, and Glazunov conducted so badly it was believed he was drunk, and to further humiliate him, St. Petersburg critics took delight in mangling a hopeful Moscow, driving Rachmaninoff almost to the point of insanity.

This fiasco and several other disappointments, including a broken love affair, seem to have struck him all at the same moment; Sergei Rachmaninoff was never the same man again. He suffered from melancholia and from doubts about his own talents to the end of his life. To the young composer’s fortune, and at his family’s persuasion, he consulted Dr. Nikolai Dahl, who was experimenting with autosuggestion and hypnotism (Ewen p. 315-16).

Dr. Dahl was a psychiatrist who specialized in curing alcoholism through hypnosis. From January till April 1900, Rachmaninoff visited Dr. Dahl daily, and sat in am armchair while Dahl repeated the suggestive formula: “you will begin to write your concerto… you will work with great facility… The concerto will be of an excellent quality…” Dr. Dahl’s treatments seem to have been miraculously beneficial to the composer’s creative ability, and also guided him into a new and happier path in his life. Dr. Dahl was the man who pulled him out of his crisis, but he never really cured him. The depression, and the trauma which he tried to escape in dissipation, gnawed at him his whole life; however, Rachmaninoff resurfaced and completed the slow movement and finale of his Second Piano Concerto, in C minor (Ewen p. 315-16; Seroff p. 74-75).

Following the immense success of his C minor, which he played at a concert with Siloti in Moscow, Rachmaninoff went on to compose the first movement the following spring. Dr. Dahl’s persuasion during Rachmaninoff’s treatment was a success; he set free the young composer’s lyric gifts. The C minor Concerto became and still is one of Rachmaninoff’s best works and one of the most successful pieces of its kind in Russian Piano literature (Ewen p. 316).

Sergei Rachmaninoff also owed his greatest debt to Tchaikovsky. The C minor Piano Concerto is a child of the celebrated B-flat minor with similar flower-laden and scented melodies and a technical display almost as theatrical. The melodies are among Rachmaninoff’s most effective and are set forth with a fine variety in the Tchaikovsky manner. The melodies, whether proclaimed boldly in octaves, sweetly sung by solo woodwinds or embedded in the soft velvet of the strings, were always given preferred treatment. (Ewen p. 316-17).

One extraordinary feature Rachmaninoff possessed was his unusually large hands. He was often seen gloved and using a heating pad on his hands. His hands were so large that it was said that he could play a chord spanning an octave and a half with his left hand. The extraordinary size of his hands may have been caused by Marfan’s syndrome, a hereditary disorder of the connective tissues that accounted for some of the painful ailments that beset him throughout his adult life, causing him occasional stiffness of the hands, arthritis, and chronic back pain. Due to the size of Rachmaninoff’s hands, many of his piano writings were full of thick-voiced chords that cannot be executed comfortably by players with small hands (Teachout par. 12, par. 52).

Isle of the Dead- Part 1

In the later part of 1906, Rachmaninoff moved to Dresden, Germany, where he remained for three years and where he found the isolation and intellectual stimulus he needed. The years between 1907 and 1909, yielded a number of large-scale works. Among his creative work were the Second Symphony in E minor; the tone poem, The Isle of the Dead; the First Piano Sonata; and, the Third Piano Concerto (Ewen p. 317).

The Second Symphony in E minor was originally an hour of performance, but the composer later sanctioned various cuts. The piece shows Rachmaninoff’s rapid rise to mastery of techniques. Ingeniously, themes are manipulated and integrated; contrapuntal skills are everywhere, and the use of instruments is exceptional. Here the composer realizes his most precious asset, the long-flowing, richly mellow themes, that he could stretch into an endless melody. However, it is due to its length, it lacks variety (Ewen p. 317; Rachmaninoff).

Isle of the Dead- Part 2

The tone poem, the Isle of the Dead, bears subtitle, To a Picture by A. Böcklin. Böcklin, a Swiss painter, achieved academic fame and popular success with this picture. The painting depicts the romantic vision of the painter, of a volcanic island north of the Gulf of Naples where whitened cliffs, cypress trees, a lifeless sea, and a boat approaching with a cargo of death is portrayed. Sergei Rachmaninoff conveyed in this piece a solemn dignity with his unusual feeling for the darker side orchestral colors, and although he successfully evoked the chill landscape and funeral mood, the piece suffers from excessive length on a single gloomy theme (Ewen p. 317; Rachmaninoff).

It wasn’t long before Rachmaninoff’s consciousness began to be influenced by the powerful influences of the West; a style that stemmed directly from the romantic masters, especially Chopin and Liszt framework of singing melodies and rich sonorities, decorated with elaborate technical embellishments. His best piano art was epitomized in his Preludes. He wrote twenty-four essays in this form, one in each of the major and minor keys. The C-sharp minor began the set in 1892, followed by the ten Preludes of op. 23, in 1903 and finally the thirteen Preludes of op. 32, composed in 1910 (Ewen p. 318).

During the years of 1910 through 1917, fifteen Etudes-Tableaux were composed in two sets, six in op. 33 and nine in op. 39. The title was intended to indicate that each piece grew from pictures of the Swiss painter Böcklin, and although powerful and closely related to the final set of Preludes, musically they do not attain the interest of the finer Preludes (Ewen p. 318-19).

As a composer of songs, Sergei Rachmaninoff remained in the romantic tradition; after all he was a son of Tchaikovsky. His songs breathe only the romantic airs, and most of them are hymns of passionate longings or lovely landscapes, and his approach to the song was similar in many ways to Schumann’s. Primarily a pianist, the accompaniment in his songs are mere means of underlining the vocal line, and by going along on a contrapuntal track of its own, the piano collaborates with the voice in expressing the poetic thought (Ewen p. 319; Sabaneyeff p.105).

In 1917 the revolution finally descended on Russia and fearing for his family, he seized the opportunity to leave Russia when he was offered a concert tour of Scandinavia (Ewen, p. 320). Sergei Rachmaninoff was a man of strong domestic inclinations and defecting Russia was heartbreaking for him. Although he yearned to return to Russia, he knew that his native homeland would ever be the same for him, so to entertain any notion of doing so would be futile; this painful yearning followed him to the end of his days.

As soon as Rachmaninoff settled in the U.S., he unfortunately realized that he would no longer earn a living as a composer; Russia made it impossible for him to profit from his works because they never consented to international copyright conventions. For almost a decade after his exile, Rachmaninoff remained silent; however, in the summer of 1926 in France, he finished what he had set out to accomplish prior to his exile, his Fourth Piano Concerto in G minor. This proved to be a disappointment for Rachmaninoff; this Concerto seemed like a pale ghost of its clanging and colorful predecessors. Nonetheless, a magnificent revival of the composer’s creative vigor came in the summer of 1934 were he wrote his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, for piano and orchestra. In a blazing virtuoso’s crown, the pianist exhibits in his work brilliance and at the same time, difficulty; from deceptively simple beginnings it grows steadily more complex and ingenious (Ewen p. 320; Teachout par. 19; McDonald par. 8).

Almost thirty years separated his Second Symphony from his third, in A minor. The later was composed in Switzerland between 1915 and 1936, and was first performed by Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra on November 6, 1939. Rachmaninoff commented to a friend that this piece was played wonderfully, but added ruefully that the public and critic’s reception was sour; unfortunately, the Symphonic Dances for orchestra that followed between 1940 and 1941, were even less interesting.

During this time, Rachmaninoff recorded extensively and made it possible for later generations to hear his music. He signed his first recording contract with Edison in 1918, and then with Victor the following year; however, the impression left on modern-day listeners were much different from those of the past and this brought him grief; Russia had robbed him of inspiration, first by Russia’s isolation from the Western movement of music, then by leaving his beloved native land, thus making him painfully aware that the world of classical music had changed beyond recognition. This was to be the last time Rachmaninoff composed (Ewen p. 321; Teachout par. 20-23; MacDonald par. 26).

In February of 1943, he canceled his remaining appearance and returned home to Los Angeles where his physicians learned that he had malignant melanoma, a virulent form of cancer. He died a month later and was buried in New York (Teachout par. 25).

Very much like Tchaikovsky’s music, Rachmaninoff attracted the admiration of the general public and hostility of many critics. At one time, the Russian advanced critics fell upon Rachmaninoff and harried him to shreds. But his greatest crime was that he was born at the time when fashion and the musical masses had drawn people to seek eminent novelty in a time where old values were overthrown. His music had more emotional and intellectual substance and is often seen as extravagantly emotional and sentimental, almost too poetical and sweet for modern times; nevertheless, in order to appreciate his talent, one has to understand that it was written in an idiom of the past. One would have to understand that this music was written by a troubled and sensitive man who longed to live in an age and in a century that had vanished into the past (Ewen p. 321; Sabaneyeff p.113-14).

Rachmaninoff’s achievement as a composer, conductor, and touring virtuoso is greatly displayed in his works. His achievement in the field of piano music was significant, for his Preludes, Etudes-Tableaux, concertos, and the Paganini Variations are among his finest music and his work is all deserving of honor, respect and admiration.

Works Cited

Ewen, David. The New Book of Modern Composers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1961.

MacDonald, Graham. “Rachmaninoff in Winnipeg: The Band of the Princess Patricia’s Regiment Meets a Russian Master.” Manitoba History (2000-01): 17. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 6 April, 2004 <http://www.epnet.com>

Rachmaninoff, Sergei. Symphony no. 1 The Isle of the Dead. London, 1993.

Rachmaninoff, Sergei. Symphony no. 2 in E Minor, op. 27. MCA Classics, 1988.

Sabaneyeff, Leonid. Modern Russian Composers. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975.

Seroff, Victor I. Rachmaninoff. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., 1950.

Teachout, Terry. “What Was The Matter With Rachmaninoff?” Commentary May 2002: 47. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 6 April, 2004 <http://www.epnet.com>

©Faithful Daughter

![5 Reasons Why Music is Important in any Society [Updated 2020] 5 Reasons Why Music is Important in any Society [Updated 2020]](https://images.saymedia-content.com/.image/t_share/MjA0NjIzNTE4NDE4MTUxMzUz/why-is-music-important.png)