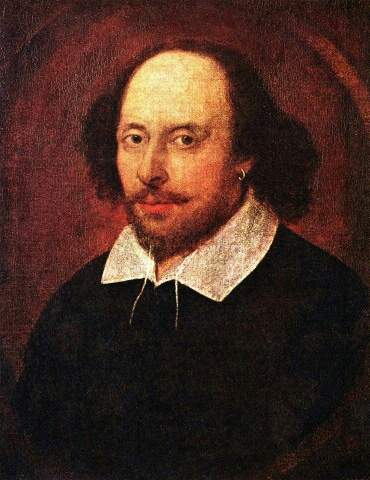

Shakespeare's Favorite Book- Exemplified in The Taming of the Shrew

Shakespeare’s Inclusion of Ovid’s The Metamorphoses to Foreshadow and Highlight the Transformation of the Character of Katherine in The Taming of the Shrew

William Shakespeare’s romantic comedy, The Taming of the Shrew (1594), is a play which consists of deception on a number of levels. These deceptions on the characters’ parts, for the purpose of achieving their individual or otherwise their masters’ goals, involve character transformation. These character transformations have various constitutions. Some of the characters change their apparel and name, taking on a superficial transformation, such as Lucentio and Hortensio, who dress up and act as tutors to gain access to Bianca. Katherine undergoes a psychological transformation after becoming the wife of Petruchio, but the nature and extent of that psychological transformation is open to debate. Shakespeare invokes the motif of change with references from the ancient author Ovid’s The Metamorphoses (8 A.D.) early in the play; Russ Mcdonald states that Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew parallels with Ovid’s mythological recounts, in that Shakespeare ”depicts a world that seems constant in nothing but change” (161). Shakespeare specifically comments on two particular stories excerpted from The Metamorphoses (Apollo & Daphne, and Io & Jove); the two male mythological characters (Apollo and Jove) are represented by the male suitor of Petruchio, while the two female mythological characters (Daphne and Io) undergo symbolically variant physical transformations which each offer a different insight into the psychological transformation of Katherine. “This attraction to metamorphosis is another manifestation of Shakespeare’s commitment to the value of play, his pleasure in the beneficial effects of costumes, roles, [and] impersonation” (Mcdonald 161). Shakespeare’s use of two Ovidian references provides a foreshadow of the psychological transformation of Katherine, which is displayed by her language and manner of behavior throughout the play, and the two mythological stories offer a dual perspective of the transformed Katherine, which allows the audience to decide which female mythological character her transformed self aligns with most.

In Scene Two of the Induction to The Taming of the Shrew, the Lord and his servants set up an elaborate ruse, in which they take the drunkard Christopher Sly and make him into a rich lord. In the waking of the drunkard, they offer him music, the activity of hunting, as well as paintings. These paintings consist of reenactments of two stories from The Metamorphoses:

Lord. We’ll show thee Io as she was a maid

And how she was beguiled and surprised,

As lively painted as the deed was done.

Third Servingman. Or Daphne roaming through a thorny wood,

Scratching her legs that one shall swear she bleeds,

And at that night shall sad Apollo weep,

So workmanly the tears and blood are drawn. (Ind. 2.54-60)

The two Ovidian stories involve a male mythological pursuer, each of whom attempts to capture the female mythological counterpart for the purpose of passion and erotic love. Apollo, the god of the sun, pursues Daphne, the daughter of the river god Peneus, honestly revealing his desire for her beauty: “The lamb runs from the wolf, the deer from lion/ The trembling-feathered dove flies from the eagle/ Whose great wings cross the sky- such is your flight/ While mine is love’s pursuit” (Ovid 45).

The second story is parallel, in which Jove, the highest of the gods, pursues Io, daughter of the river god Inachus, with the interest of love: “Now it so happened that all-seeing Jove/ Saw Io walking by her father’s stream/ And said, ‘O lovely child, and you a virgin!/ Such beauty merits the rewards of Jove” (Ovid 47). In each of the mythological recounts, the male pursuer makes openly known the intent of passion and interest of relationship. Petruchio aligns with both of the mythological pursuers in that he makes openly known his intent for marriage and physical relations with Katherine: “Now, Kate, I am a husband for your turn,/ For, by this light, whereby I see thy beauty-/ Thy beauty that doth make me like thee well-/ Thou must be married to no man but me” (2.1.265-8). Petruchio also remains the exception in the play regarding honesty, in that he uses no deception or ruse while attempting to achieve the ends of marriage in Katherine. He addresses Katherine’s father Baptista directly with his wishes for courtship: “I am a gentleman of Verona, sir,/ That, hearing of [Kate’s] beauty and her wit,/ Her affability and bashful modesty,/ Her wondrous qualities and mild behavior,/ Am bold to show myself a forward guest” (2.1.47-51). It is important to consider the aspect of the likeness of Petruchio to these male mythological pursuers, before delving into the dual concepts of the female mythological transformations which shed light on the character of Katherine.

While Petruchio is likened to the two male mythological pursuers, Katherine can be paralleled with both female mythological characters, that of Daphne and Io, as the one who is pursued. In Petruchio’s initial encounter with Katherine, she negatively responds to his interests for marriage. When Petruchio tells Katherine that he is moved to woo her for his wife, she boldly replies: “Moved! In good time, let him that moved you hither/ Remove you hence” (2.1.195-6). Katherine’s rejection of Petruchio, which ranges from this verbal offensiveness to physical abuse (2.1.217), is seen in both of the female mythological characters of Daphne and Io, in their rejections of Apollo and Jove, respectively.

The essential controversy which is raised in the character of Katherine concerns the nature of her psychological transformation after becoming married to Petruchio. The audience must decide whether Katherine alters her behavior with cunning to survive the expectations of her social situation, while still inwardly retaining her shrewdness, or if Katherine truly metamorphoses, rendering her a subdued and manipulated character, formed by Petruchio in a patriarchal social atmosphere. While considering this controversy, the two female mythological characters of Daphne and Io undergo transformations by supernatural means which each symbolically represent a different outcome concerning the final psychological status of Katherine.

The female mythological character of Daphne, while attempting to evade Apollo in his pursuit, calls upon her father, the river god Peneus, asking him to cover her with nature in order to hide from Apollo. Her desire is granted and, just before being apprehended, she becomes part of her surroundings:

A soaring drowsiness possessed her; growing

In earth she stood, white thighs embraced by climbing

Bark, her white arms branches, her fair head swaying

In a cloud of leaves; all that was Daphne bowed

In the stirring of the wind, the glittering green

Leaf twined within her hair and she was laurel. (Ovid 46)

Daphne’s transformation into the evergreen laurel is significant, as laurel was made into wreaths and crowns in Ovid’s time and placed on the heads of war heroes and athletic winners as a symbolic object of victory. Katherine’s transformation in The Taming of the Shrew can be seen in light of Daphne, in the sense that Katherine becomes Petruchio’s object of victory as his wife, yet still is not truly imprisoned by him, just as Daphne remained out of the grasp of Apollo. This positive depiction of Katherine, and her ability to adapt with personal integrity, holds true to Shakespeare’s use of the Ovidian metamorphosis, creating an environment for the main character “in which obstacles can be overcome and wishes fulfilled, in which change is beneficent and happiness attainable” (McDonald 161).

The uncertainty of the nature of Katherine’s transformation is raised in her final monologue; it is difficult to gauge the sincerity of her comments which inform the audience that she seems to advocate the idea of marriage, even glorifying the state of being a wife:

Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper,

Thy head, thy sovereign- one that cares for thee,

And for thy maintenance commits his body

To painful labor both by sea and land,

To watch the night in storms, the day in cold,

Whilst thou li’st warm at home, secure and safe;

And craves no other tribute at thy hands

But love, fair looks, and true obedience:

Too little payment for so great a debt. (5.2.146-154)

When considered with Katherine’s previous shrewdness and physical abuse of Petruchio, Katherine’s comments can be considered a cunning cover-up of her true rebellious nature, which she retains, but must conceal, in adhering to the social expectations of marriage which she is unable to escape, but must survive. Ultimately, in light of the transformation of Daphne, Katherine becomes Petruchio’s laurel crown while still retaining her own identity and individuality as a woman who can never be truly manipulated.

Unlike Daphne, who is transformed by her own request to escape the selfish intentions of Apollo, the female mythological character of Io is transformed against her will, and in a much more inhumane fashion. Jove, who is highest of the gods, sees Io and insists on attaining her for her beauty. When approached by Jove, Io chooses to run, but to no avail: “But Io ran,/ Steering her way across the fields of Lerna,/ Until she entered the shady groves of Lyrcea,/ And there, cloaked by a sudden thundercloud,/ Jove overcame her scruples and her flight” (Ovid 48). Juno, who is the wife of Jove, senses his betrayal of her and descends to earth. To hide his act of deceit, Jove transforms Io against her will: “But thoughtful Jove felt the arrival/ Of Juno’s spirit in the air, and changed the girl/ Into a milk-white cow” (Ovid 48). Io then, as a cow, is given to Juno as a gift, whom thereafter delivers her over to a hundred-eyed monster named Argos who treats Io very cruelly. Ultimately, Io’s fate is to remain indeterminately transformed. Io is depicted as a girl who is tortured by her metamorphosed state, in encountering her family:

Nor did her sisters know

That it was she who walked beside them, nor

Did her father guess that she, the creature

Whom they caressed, was Io, his hand kissed

By her thick tongue. If only she could speak,

Tell him her name, her story- he could save her! (Ovid 49)

Katherine’s transformation in The Taming of the Shrew can be observed in light of Io, as a female character who is subdued and manipulated against her will, resulting in the alteration of her personality and character which is beyond repair. Aside from the opinion that Katherine retains her identity and conceals her rebellious nature in order to survive the inescapable fate of marriage, there is the opposite perspective that Katherine is truly tamed by Petruchio and psychologically metamorphosed, that she loses her will to remain an individual, and becomes the tame, submissive wife which is commonplace in this patriarchal environment. Ann Christensen comments on the transformation: “Katherine's complicity in her own idleness seems to document the success of her taming, but into what is she tamed? While the husband performs tasks associated with mercantile adventure and good husbandry such as caring, maintaining, and watching, Katherine states her own part of the bargain only abstractly; we might well ask, ‘What do “love, fair looks and true obedience” look like?’ Her argument occludes women's work as it differentiates an emergent bourgeois feminine sphere apart from ‘the world’, the public sphere proper to men” (305-6). Katherine’s language in her final monologue, if the audience is to assume that she is being forthright and revealing her true thoughts, seems to portray her as this manipulated and subdued character, as Io was:

But now I see our lances are but straws,

Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare,

That seeming to be most, which we indeed least are.

Then vail your stomachs, for it is no boot,

And place your hands below your husband’s foot,

In token of which duty, if he please,

My hand is ready, may it do him ease. (5.2.173-9)

This language, which implies subservience of wife to husband, is where the controversy arises, whether Katherine’s condition is psychologically altered, or her public behavior is modified for the sake of survival. Subsequently, the audience must decide which of the two female mythological characters most aptly represents the final status of Katherine.

A valid argument remains that neither of the two extremes apply to Katherine’s transformation; there is a possibility that Katherine finds a happy medium, in which she is tamed to an extent in satisfying her familial expectation of marriage to Petruchio, yet still retains the sharp, shrewish nature she is previously infamous for, simply by learning to conceal it with her language in the public eye: “Less than what she says, the fact that she is speaking at all is significant, as it shows that she has not been tamed, but rather has achieved a smoothness around her bristled edges. Not submissive, but tempered” (Abate 306). Katherine’s union with Petruchio appears to be a solution, not necessarily for Katherine but more for the benefit of her family. After all, her marriage appeases her father’s will to marry her first, satisfies Petruchio’s desire to “wife it wealthily” (1.2.74), and opens her younger sister Bianca to the prospect of marriage, also to the benefit of Bianca’s multiple wooers. If Katherine is able to conform, at least publicly, for the prosperity of her family ties, then her decision to adapt her language to appear tame and submissive is honorable. Michelle Lee comments on Shakespeare’s use of metamorphosis regarding the character of Katherine, and that the author “tends to advance certain Ovidian themes, principally the notion of continuity through change and the efficacy of love as a medium of mutability” (Lee 291).

Russ Mcdonald states that “it may even be true to say that [Ovid’s] The Metamorphoses was Shakespeare’s favorite book” (160). Shakespeare’s use of metamorphosis in The Taming of the Shrew, whether it is physical or psychological, is a direct reflection of the author’s respect for, and inspiration by Ovid. It is apparent that the author’s inclusion of these two mythological stories is intentional, and would otherwise be obscure if they did not relate to the transformation of the play’s main character. Furthermore, Shakespeare’s textual references to The Metamorphoses not only add depth to the transformation of the character Katherine with her relation to Io and Daphne, but also assist in placing Shakespeare’s play within the greater scope of traditional and historic literature. Shakespeare’s foreshadowing of Katherine’s transformation by inserting the Ovidian references to the female metamorphoses of Daphne and Io display the author’s ready recollection of the knowledge of the mythological realm in The Metamorphoses. The mythological stories of Io and Daphne each carry a symbolic significance which can be applied to the character of Katherine, in which the concept of transformation is early introduced by Shakespeare, and remains at the forefront of The Taming of the Shrew throughout its duration.

Works Cited

Abate, Corinne S. "Neither a Tamer Nor a Shrew Be: A Defense of Petruchio and Katherine.” 2003. "The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare." Shakespearean Criticism. Ed. Michelle Lee. Vol. 97. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006. 287-368. Literature Criticism Online. Gale. CIC University of Wisconsin Parkside. 5 May 2009 <http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/LitCrit/parkside/FJ2675450005>

Christensen, Ann C. "Of Household Stuff and Homes: The Stage and Social Practices in The

Taming of the Shrew." 1996. "The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare." Shakespearean Criticism. Ed. Michelle Lee. Vol. 107. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2007. 302-352. Literature Criticism Online. Gale. CIC University of Wisconsin Parkside. 5 May 2009 <http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/LitCrit/parkside/FJ2633550005>

Lee, Michelle. Introduction to "Metamorphosis in Shakespeare’s Works." Shakespearean

Criticism. Ed. Michelle Lee. Vol. 96. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006. 291-380. Literature Criticism Online. Gale. CIC University of Wisconsin Parkside. 5 May 2009 <http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/LitCrit/parkside/FJ2675350005>

McDonald, Russ. The Bedford Companion to Shakespeare. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001.

Ovid. The Metamorphoses. Trans. Horace Gregory. New York: Penguin Group, 2001.

Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. Ed. Robert B. Heilman. New York: Penguin

Group, 1999.