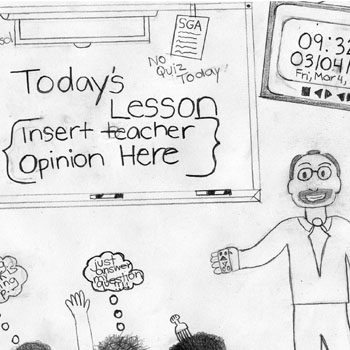

Should History Teachers Express Their Political Opinions in Class?

Can Opinions Be Avoided?

About a week ago, we were talking about the writing of the Constitution in one of my Early American History classes. At the time, the government had finally come to an agreement to reopen the federal government and to raise the debt ceiling. So in the course of discussion, a student raised his hand and asked me who was responsible for this recent “crisis.”

When current events come up in an American History class, what is my role as an instructor? By nature, any discussion of modern political events could require me to present a personal opinion. And even if it is possible for me to avoid expressing my opinion on some subject, it can be very tempting to share my views, particularly when it comes to important topics. Some would argue that the instructor should stick to the subject matter. So in my case, I should stick to the past, not get caught up in a political controversy of the present. I am supposed to be a history teacher, after all, not a political pundit. And if a teacher uses his position of authority in order to express personal opinions, he or she is has become more of an indoctrinator than a teacher. Just stick to the facts, Mister History Teacher.

Personally, I think it is essential for any history instructor to connect the events of the past to the present. If we do not attempt to learn from the past and to make connections to current events, then the whole exercise of studying history is rather pointless. This is why I continually make references to current events in order to make the circumstances of the past more relatable and relevant for my students, the majority of whom likely believe that a history course is a pointless ordeal that one must tolerate in order to fulfill general education requirements. And even if I were to somehow avoid talking about current events, controversial questions regarding the past are going to come up, many of which have modern implications. Unless a history course consists of nothing but memorizing trivia, historical questions will be raised that have no definitive answers.

So if I cannot avoid expressing opinions, should I try to be "fair and balanced," whatever the heck that means? Or should I try to call it like I see it, reminding students that they should always feel free to take my opinion or leave it? This doesn't mean, of course, that my opinion has to be blatantly partisan. There is also something to be said for playing devil’s advocate, expressing views commonly held by others. But all points of view, whether discussing the present or the past, are not created equal, and there are far too many points of view on any subject to cover them all. So in order to avoid a dry class in which the teacher is some sort of a perfectly “objective” robot creating the impression that there is no such thing as truth, there are times when I will let my humanity show and say what I think. And since I am working with supposed adults, they need to develop the capacity to recognize when I am expressing an opinion and to evaluate the argument that I am making. It’s rare when students will speak out strongly against what I am saying, but I relish those moments when they come. Studying history, after all, is as much about raising good questions as struggling to find answers, and the last thing any decent teacher wants is a bunch of students mindlessly copying down notes in order to memorize the “truth” for the next test. Unfortunately, this is what we community college teachers tend to get, in spite of whatever efforts I might make to get them to express their opinions on various subjects.

So in the situation I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I gave sort of a multifaceted answer to this particular student’s question. My initial response was pretty simple: “it depends on who you ask.” The House of Representatives passed a spending bill that funded everything except for Obamacare, knowing that the Senate would reject it. When neither side would budge, we had a shutdown. So Republicans blamed the Senate for rejecting a spending bill, causing the shutdown. Democrats blamed the Republicans for choosing to shut down the government rather than funding legislation that had been passed by Congress and signed by the President. Party affiliation and/or feelings about the Affordable Care Act pretty much determine which side you blame.

I did mention, however, the polling data which indicates that Republicans have been blamed more than Democrats. This is largely because some prominent Republicans had been saying for some time that they were willing to shut down the government over Obamacare. This then created the impression that Republicans initiated the shutdown. But once again, whether someone agrees with the majority of Americans probably comes down to party affiliation. Still, politics is about perception, and the public response to the games that politicians play is often more important than the actual policies being implemented. In the end, the long term political impact of this shutdown will likely be far more important than the immediate effects of those sixteen days.

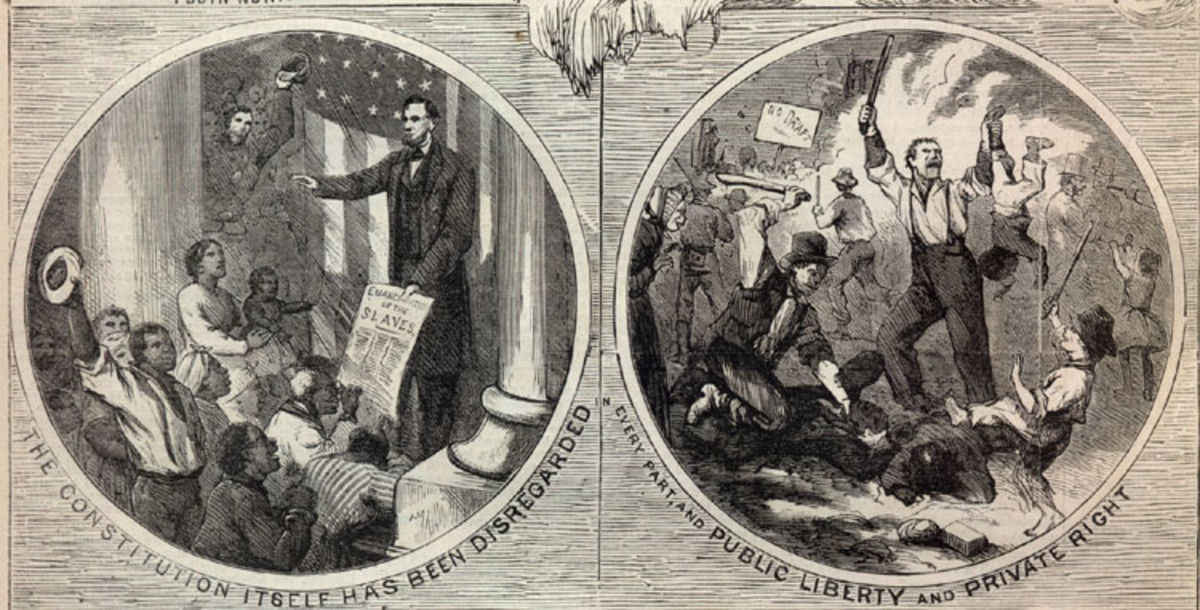

In addition to giving me a chance to cover the basics of this “crisis,” this student’s question created a good opportunity to describe one of the problems with the division of power/checks and balances system that I was covering in class at the time : it can be hard to get things done, especially when political parties come into play. The Constitution framers did not generally like the idea of political parties, a fact I point out more than once as we go through our class. Given current events, you can kind of see why. Still, this complicated process, in theory, should lead to better decisions and prevent any individuals from amassing too much power. But it sure can be a pain in the ass.

This student’s question also gave me a chance to have a quick discussion about Senate rules regarding filibuster/cloture/etc., which have made it so the Senate needs 60 votes to get much of anything done. Because of these rules, the party in control of the Senate cannot play the same game as those in charge of the House, passing whatever bills it wants and blaming the other chamber for “inaction.” In my view, this goes against the original design of the Constitution in which a simple majority is needed to pass a bill in the Senate, making it even harder to get things done than the framers intended. But I guess you could argue that this is just my opinion. I didn't spend too much time on the filibuster topic, however, because I was hoping to keep my students somewhat awake. It was a three-hour community college night class, after all. Plus, I needed to get back on topic, describing our stupid system for electing presidents. But that’s a whole other story, and I will spare you my opinion on that one.