- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Sky City: The Acoma Pueblo

The Sandstone Stairway That Has Carried My Heart and Soul The Closest To Heaven

One of the most beautiful and spiritually powerful places I have ever been is Sky City, the Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico. To this very day thoughts of Sky City inspire me and make my soul long to be there. There have been many times in my life where I just want to leave everything to live amongst the people of the Acoma Pueblo. There is something there that attracts my heart and draws me to an unnatural feeling that calls out to me... like a silent voice that is crying out... something that stirs my soul....telling me that... "I belong there."

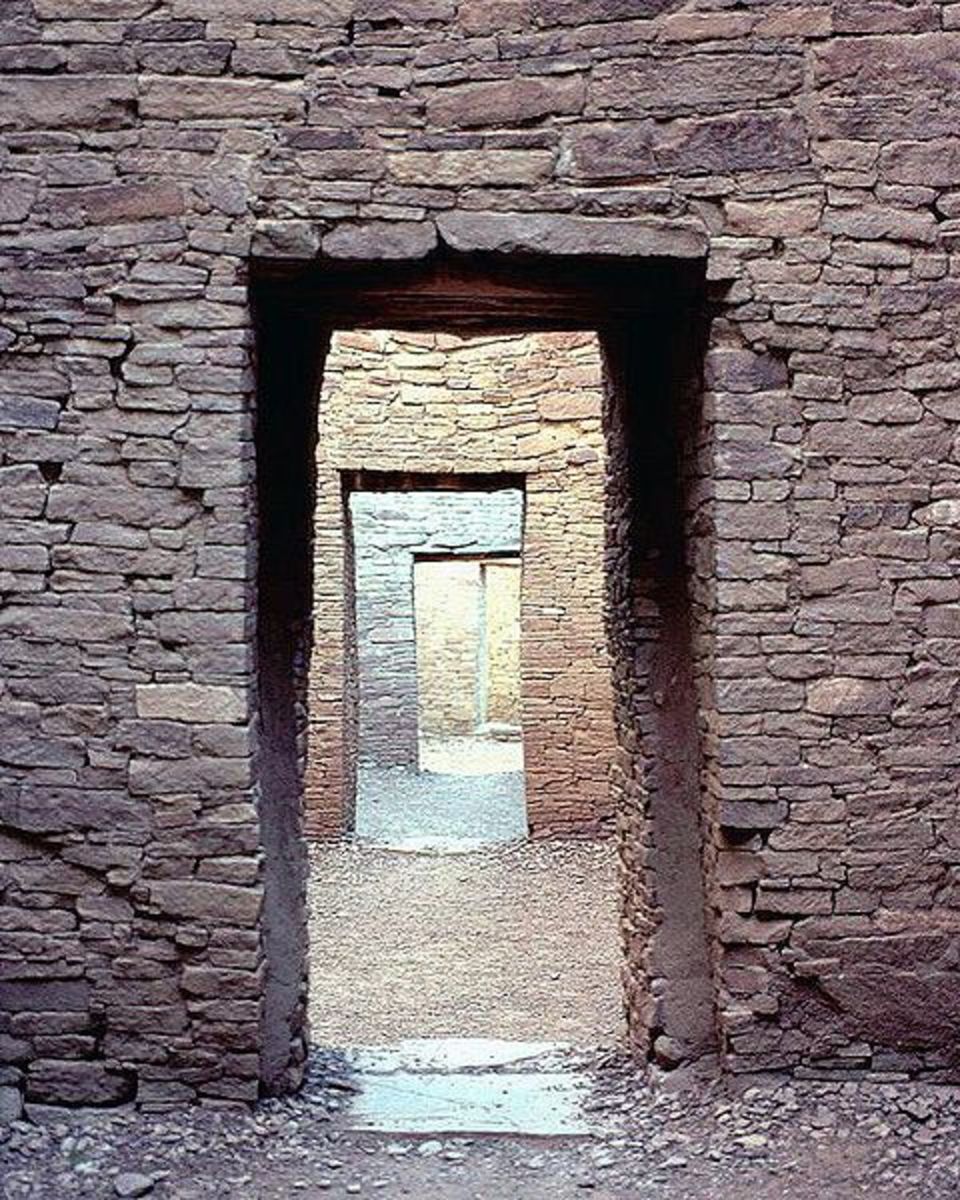

Many believe that the Acoma Pueblo has been around since the 12th century or quite possibly earlier. Sky City is believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States. High atop a mesa, the Acoma Pueblo was chosen partly because of its strategic position against raiders. Gaining access to Sky City is difficult, the face of the mesa is sheer, and in ancient times, the only way to the top or out of the pueblo was by hand-cut staircase carved into the sandstone (which walking down can be adventurous.)

There are fewer than 50 tribal members of the Acoma that live year-round in the earthen homes of Sky City. The people who live there care-take the massive San Estévan del Rey Mission, which was completed in 1640. Both the mission and pueblo are Registered National Historical Landmarks. Many of the tribal members choose to live in the nearby villages.

The Sky City Cultural Center and Haak’u Museum offer insight to the Acoma's living history as well as their culture, and tours of Sky City are conducted by native Acoma guides. There are some restrictions to photography and I don't believe that video recording is allowed.

Acoma Pueblo: Climbing Down The Steps

The Acoma: The People Of Sky City

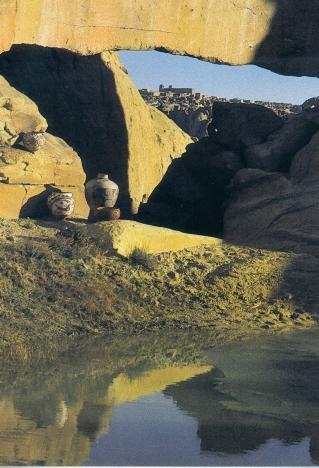

For centuries the Acoma people had dry-farmed the valley below the Acoma Pueblo using irrigation canals in the villages closer to the Rio San Jose River. The Acoma were known to trade, not only with neighboring pueblos, but also over long distances with the Aztec and Mayan peoples.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, in 1540, was the first European to ever lay eyes on the Acoma Pueblo. Coronado described the Pueblo as: "One of the strongest ever seen, because the city was built on a high rock. The ascent was so difficult that we repented climbing to the top."

Close to sixty years after Coronado, Sky City was almost destroyed by Govorner Juan de Oñate and 70 of his troops. When the troops attacked the pueblo in retaliation for the killing of 13 Spanish soldiers by the Acoma when they tried to take grain from the Spaniard's storehouses.

A Peace Offering

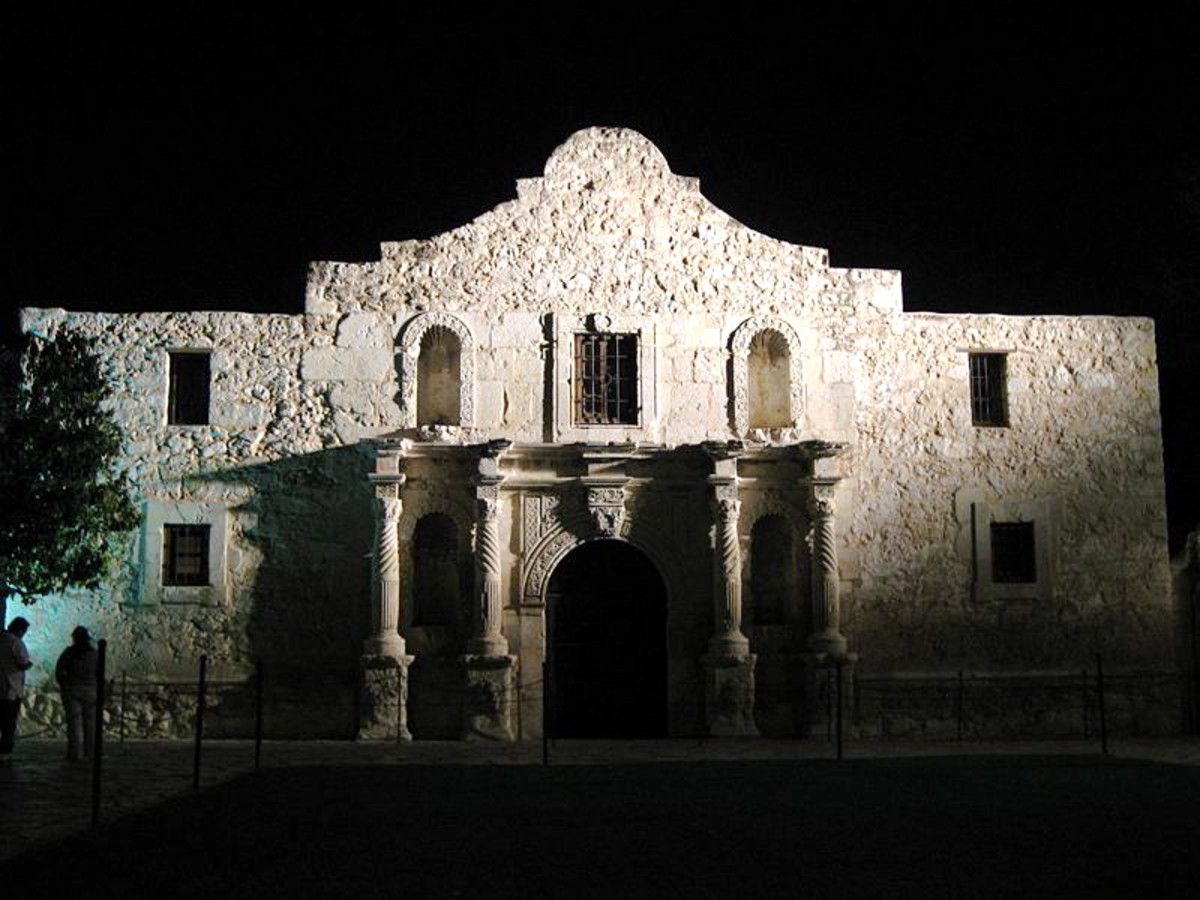

The Spanish began to build the San Estéban del Rey Mission in 1629, as a gesture of peace (and probably an attempt at religious conversion) with building materials that were hand carried and hauled up the steep slopes of the mesa. The mission’s 30-foot beams were carried from Mount Taylor, some 30 miles away from the Pueblo. The dirt for the cemetery was carried up the mesa from the valley below. Under the watchful eye of Friar Juan Ramirez the mission was finally completed in 1640.

According to legend, Friar Juan was allowed entrance to Acoma when he saved an infant from falling off the edge of the mesa as he approached. His delivery of the child back to the mother's arms was considered a miracle. The building of the mission represents a tremendous amount of toil. All the religious articles on view inside the mission date from the mid-1600's to the later 1800's.

Following Their Ancestors

The Acoma people still continue the traditions of their lineage, which can be traced to the former dwellers by the older ruins to the north and the west of the today's pueblo. Families still practice their ancient religion while still 95% of families had converted to catholocism. Throughout the years celebrations and feasts are held for relegious and historic occastions (visitors are allowed to attend, but they most be respectful and aware of local protocol.)

Acoma Sky City

Carrying On The Traditions Of The Acoma

The social order at Acoma is made-up of a number of clans, and each is recognized through the mother's lineage. The oral native tradition tells of the origin of human beings from the underworld called the Shipapo. "In the beginning, there were two sisters, Nautsiti and Latiku, who gave birth to all living things. Henceforth, they all multiplied. The sisters parted and Nautsiti journeyed to the East while Latiku fostered the Pueblo ways. As Latiku's children were born, each was given a clan name."

Every clan assumes an important function in ceremonial and social activities as well as in the political system of the Pueblo. The elders of each clan ensure that discipline and traditions are continued through succeeding generations. Everyone is responsible for tribal life. When the oldest female in a clan dies, ownership of the home is passed down to her youngest daughter.

The original homes were three stories high. The first floor was used for storage, the second for sleeping and the third for cooking. A block-wide section of these homes still exists. Most of the others, however, are one or two stories high. They still have dirt floors. A combination of dirt and straw is used to plaster the outside walls. Originally, slices of mica were used for windows to allow light inside, but in the late 1920's the mica was replaced with glass.

Sky City has never had the luxury of running water. Water is still carried up in buckets from the base of the mesa. The only difference is now, the buckets are carried up by family car. A series of wooden and fiberglass outhouses can be seen at one end of the pueblo. Although electricity has never been introduced to the mesa, some families do have generators, primarily because of their school-age children. A county bus transports them to nearby schools.

Many of the Acoma people are artists who produce the famous and highly prized Acoma pottery. Using native white clay, they mold, etch and paint unique red, white and black designs on various types of thin-walled pots.

Artist - Norma Jean Ortiz - Acoma Pottery

The Spanish And The Acoma

Late in the summer of 1540, the Acomas saw a vanguard of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s expedition appear from the west, out of the desert. They descended the mesa to confront the Spanish force, which, under the command of Don Hernando de Alvarado, comprised twenty soldiers and several Pecos Pueblo Indian guides. Unintimidated by bearded men who wore armor, rode strange animals and carried muskets, swords and crossbows, the Acomas first challenged the Spaniards to fight, then stood down and allowed them into the pueblo.

"The village was very strong," said Pedro de Castaneda, a chronicler of the Coronado expedition, "because it was up on a rock out of reach, having steep sides in every direction, and so high that it was a very good musket that could throw a ball as high… There was a broad stairway for about 200 steps, then a stretch of about 100 narrower steps, and at the top they had to go up about three times as high as a man by means of holes in the rock… There was a wall of large and small stones at the top, which they could roll down without showing themselves, so that no army could possibly be strong enough to capture the village. On the top they had room to sow and store a large amount of corn, and cisterns to collect snow and water… They made a present [for the Spaniards] of a large number of [turkey] cocks with very big wattles, much bread, tanned deerskins, pine [pinon] nuts, flour [corn meal], and corn."

In the snows of the following winter, the remainder of Coronado’s expedition passed the mesa. "…the natives, who were peaceful, entertained our men well, giving them provisions and birds…" said Castaneda. "Many of the gentlemen went up to the top to see it, and they had great difficulty in going up the steps in the rock, because they were not used to them, for the natives go up and down so easily that they carry loads and the women carry water, and they do not seem even to touch their hands, although our men had to pass their weapons up from one to another."

Nearly six decades later, in the fall of 1598, the Acomas again found bearded Spaniards who wore armor, rode horses and carried muskets and swords at the base of their mesa, "the best situated Indian stronghold in all of Christendom." The Acomas had learned that these soldiers represented Juan de Onate’s enterprise to seize and colonize the pueblo lands of the Southwest. With barely concealed hostility, they invited Onate and his men to ascend the mesa, to the village. A warrior invited Onate to enter a ceremonial chamber, which hid a party of assassins. Onate wisely declined. The Keresan-speaking tribal elders listened, mystified, as the Spanish-speaking Onate administered to them the customary ceremony of Indian submission to the Crown and the Church, "And those," said Onate, "who render obedience can never again withdraw their allegiance under penalty of death." Those words would become prophetic.

The Acomas watched Onate and his force leave, headed west. They waited patiently. A few weeks later, they laid an ambush for Onate’s nephew, Juan de Zaldivar, who led a force of 31 soldiers to Acoma, en route to join his uncle. In a brutal battle in the village, the Acomas killed Zaldivar and ten of his men. He fell, "delivered unto that eternal sleep to which we are all doomed someday," said Gaspar Perez de Villagra, Onate’s chronicler.

The Acomas could not have known what Onate planned for retribution, that "penalty of death." They could not have known that Onate, with the support of his colonists, declared guerra de sangre y fuego, war by blood and fire—war without quarter, without mercy. In the ice and snow of January, 1599, the Acomas saw the Spaniards return, a force of 72 heavily armed soldiers commanded by Vicente de Zaldivar, Juan de Zaldivar’s brother. From the precipice of their mesa, the Indian hurled insults, ice, stones, arrows and spears at the Spaniards.

On the afternoon of January 22, Acoma braced for attack. The warriors heard the call of trumpets, signaling the beginning of a Spanish frontal assault. They rushed to the top of the ascending trail, prepared to launch a fusillade of stones down on their attackers. They soon discovered that the trumpets had been a diversion, a cover for a dozen Spaniards, led by Zaldivar, who had gained entry into an undefended side of the pueblo. The Spaniards had, said Villagra, "climbed the high walls of this immense mass of stone…for there were none to oppose us."

With the beachhead established, the Acomas could not prevent the entire Spanish force from overrunning their village. They fought with prehistoric club, arrow and spear against Spanish cannon, musket, sword and dagger. They fought house-to-house, hand-to-hand, for three days, falling to superior arms, leaping suicidally over the precipice, burning in the conflagration of battle. The Acomas died by the hundreds. They saw their community, where their lives had begun anew after the great storm centuries earlier, lying in ruins. They had killed not a single Spaniard. (Only one had died, accidentally shot by one of his own men. Others suffered wounds.) The surviving Acomas, about 500, mostly women and children, surrendered. "…those who render obedience can never again withdraw their allegiance under penalty of death."

At the height of the battle, the Indians had seen (said Zaldivar’s soldiers) the spiritual figure of a Spaniard astride a white horse, hovering protectively above the Spaniards, wielding a flaming and deadly sword. A woman of transcendent beauty rode by his side. The Indians had seen (said Zaldivar’s soldiers) Santiago, the patron saint of Spain, and they had seen (said Zaldivar’s soldiers) the Virgin Mary herself. They had seen a miracle.

The Keresan-speaking Acomas stood trial before the Spanish-speaking judge and jury, with conviction a foregone conclusion. Onate handed down the sentences:

- Males over 25: loss of the right foot, 20 years of slavery.

- Males 12 to 25: 20 years of slavery.

- Two Moquis Indian visitors: loss of right hand, a warning to their own pueblos.

- Women over 12: 20 years of slavery.

- Children under 12: a Christian upbringing under a Franciscan priest.

Sixty small girls found themselves bundled off to religious training in convents in Mexico City. They would never see their families nor Acoma again.

Father Ramirez

A few years after the disastrous defeat, Acoma men and women began to slip the bonds of slavery and return in a trickle to their village on the mesa, that place to go back to. They began to reconstruct their homes and kivas, reestablish their fields and rebuild their lives. Aging men with a missing right foot fueled continuing fires of hostility and bitterness toward the Spanish.

Three decades passed before they found a renewed sense of purpose. It came from an unexpected source, a solitary and unarmed priest, Father Juan Ramirez, who appeared from nowhere one day like a tribal deity on the ascending trail to the mesa top. The Acomas attacked him with arrows, which were deflected by his habit. In the melee of the attack, a little girl tumbled over the precipice. They watched Father Ramirez pray over her. She revived from her fall, unharmed. A woman agonized over a dying infant. They watched the father pray over the baby, who recovered from its illness, cooing.

Seeing their arrows deflected and their children saved, the Acomas believed that Father Ramirez had supernatural power, and they accepted him as a spiritual leader. Under his guidance, they undertook the construction of a great mission church on the top of their barren mesa. Over 12 years, they hauled 20,000 tons of earth and stone on their backs, up the trail from the plain, to raise walls 10 feet thick. They carried dozens of timbers, or vigas, 40 feet in length, 14 inches in diameter, from the flanks of Mount Taylor, 40 miles to the north, to construct the roof. They hauled up soil for the churchyard, which lies at a walled edge of the Mesa, before the structure’s massive twin bell towers. The mission church rose as a mighty fortress, like the mesa itself, a monument to sacrifice and suffering, with Saint Stevens as its patron saint.

Seventy four Acomas – men and women – died in its construction. Moreover, as James Paytiamo, an Acoma, said in his 1932 book Flaming Arrow’s People, "I am told by [my people] that at the time this church was being built there was great famine at Acoma and that the people, when their regular food was gone, first ate cactus, then chewed their buckskins, and finally ate each other."

A Measure of Revenge

The tragic events of the pueblo’s past still have a powerful hold on the tribal memory . "If you go to the southwest side of the Acoma mesa," said Paytiamo, "you can still see under the overhanging bluff the smoke-stains from the Spanish cannon, made when the conquistadores came and took my people’s land away from them and tried to break down the rock mesa with their cannon, and there is still the remains of the little fort which my people built on the southwest top, with little windows from which they shot their arrows."

More recently, in early January of 1998, four centuries after Onate began the Spanish colonization of northern New Mexico, the Acomas finally got a measure of revenge. They had watched with growing resentment as the visitors’ center near Onate’s first settlement raised a bronze sculpture of the conquistador mounted heroically on his horse, a celebration of the 400th anniversary of his expedition. The Acomas attacked "Onate" in the dark of night, not with arrows and spears, but with an electric saw, with which they separated the bronze Spaniard from his right foot.