- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

Conquest - 8: 'The Danes Are on Their Way!' (Be Careful What You Wish... Help Can Cost)

It was all very well asking the Danes for help against William, but they would not do so out of the goodness of their hearts. There had to be profit in risk

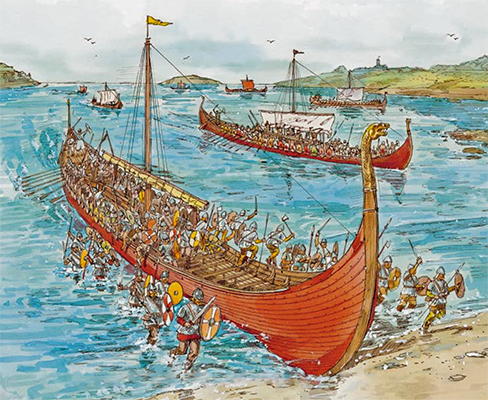

Not only the Danes under Svein Estrithsson and his brother Jarl Osbeorn were asked to intervene to help fight William, if possible oust him. The Dublin Danes under King Diarmuid of Leinster were also asked, on behalf of Godwin Haroldson and his brothers Eadmund and Magnus. So whilst Godwin led raids on the Gloucestershire and Somerset coasts in 1068, the Northumbrians had approached Svein for help to take York and the territory between Tees and Humber.

There had to be something on offer, to tempt them. In Godwin's case it would be the abbey and church at Tavistock in South Devon. Not only were they unsuccessful in Gloucestershire and Somerset - at least one local thegn died in his duty to uphold the king's laws - but they had been betrayed in South Devon. Read on to see how events unfolded...

Peter Rex illustrates the struggle against the Normans that began almost as soon as William was crowned. Portents of what was to come showed in the handling of the local population by the duke-king's guards outside the abbey church of the West Minster. When the shouts came from within at the crowning rite, 'Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!' the Norman guards set fire to the nearby homes.and assaulted the inhabitants.

Worse was to come.

AD 1069, Harold's sons failed to ignite rebellion in the west, and the Danes land in the Humber

The northern nobles were unlikely to have had any direct contact with Godwin Haroldson and his brothers, Eadmund and Magnus. The raiding on north and south Devon, and the Somerset and Gloucestershire shores of the Severn by Harold's sons in the summer of 1069 was seen as an abortive attempt at a rallying cry against the king. The attempts hardly caused ripples beyond the West Country.

It is likelier to have been co-incidental with other sporadic risings. King Diarmuid of Leinster had helped Godwin Haroldson's father in 1051 with men to help Earl Godwin's regain his earldom from King Eadward 'the Confessor'. Godwin Haroldsson sailed from Dublin with nine ships of his own men and those Dublin Danes who felt there might be some gain for them in England.They landed on the south coast near the River Tavy. The nine manors in the Stanborough Hundred, reported in Exon Domesday (1086) to have been devastated by the Irish were in all likelihood to have been ravaged at this time. Their raiding met with little support and they were driven off by the Breton Count Brian and William 'Gualdi' with the Devon fyrd. Legend has it that Magnus was wounded badly in one of the battles and taken to his former holdings in Sussex where he died of his wounds. Another legend tells that he did not die but took holy orders. No-one knows for sure what happened to him or his brothers after this. They may well have joined their mother and grandmother whence they had fled in Flanders after leaving Flatholme in the Bristol Channel.

Harold's sons were long gone from England when the Danes showed on the east coast. Their role in the English revolt against King William is stressed in all accounts, but their aims are hard to assess. The fullest account of Svein Estrithsson's possible motives is given by the Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who shows him as being moved by the death and disaster which overtook his men in King Harold's fight on Caldbec Hill near Hastings. Amongst Harold's men were Danes and Anglo-Danes, born in England of Danish stock or of mixed Anglo-Danish parentage. Orderic may have implied that the Anglo-Danish nobles of York were in some sense answerable to Svein or under his protection. Another explanation for Svein's intervention has more bearing on fact. It could be he saw Harold's death as Svein's cue to claim the English throne as a successor to Harthaknut. Svein had told the German missionary Adam of Bremen of a promise made to him by Eadward when he took the throne in 1042 after the heirless Harthaknut's death, that Svein should be his legal heir. It is highly unlikely that Eadward ever made such a promise, and it is hard to say how seriously Svein took the claim. Nevertheless his son Knut must have believed in it, and subsequent kings of Denmark revived the claim until 1193, when Knut VI made over his 'right' to the English throne to Philip Augustus.

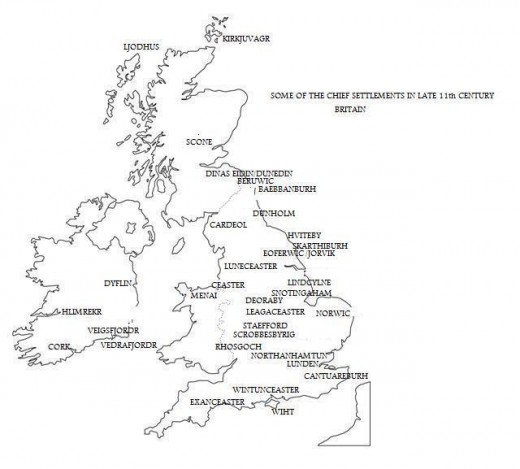

Despite this it is far from clear that the fleet sent to the Humber in 1069 came over to fulfil Svein's claim, nor how such a claim would have sat with the election by the northern rebels nobles of Eadgar 'the aetheling' as king. Svein's motives may be confusing, but his actions speak for themselves. He took no chances in coming and sent instead his brother Jarl Osbeorn as well as two sons, Harold and Knut. With them came Bishop Christian of Aarhus. The fleet of around two hundred ships followed the old Norse raiding route, striking first at Dover and Sandwich. moving north across the mouth of the Thames to land at Ipswich. A foray was made inland from here to Norwich along wide waterways. From there they struck course across the Wash then along the coast of Lincolnshire for the gaping mouth of the Humber. Their aim was to breach the defences of the main ports and hem in the shipfyrd. They succeeded in this, William having no spare ships with which to outflank the rebels at York. He had to move overland.

The Danes arrived in the Humber between the two feasts of Saint Mary: Assumption (15th August) and the Nativity (8th September). They were met by Eadgar, Earl Gospatric, Earl Waltheof, Maerleswein the sheriff of Lincoln, Siward 'Bearn', Arnkell and the sons of Karli, Hold of East Yorkshire 'with all the Northumbrians and all the people, riding and marching with an immense host, rejoicing exceedingly'. Archbishop Ealdred's was the only dissenting voice, and in any case he was dead by September 11th, soon after the Danes' landing.

The king was hunting in the Forest of Dean when the news reached him of the Danes' landfall in the Humber. He sent word to York to warn his castellans, who answered over-confidently that they could 'hold out for a year' if need be. On 19th September the houses around the two castles were set on fire lest the enemy use the wood to fill the ditches for an assault on the castles. The flames spread, engulfing the whole city including the old Saint Peter's cathedral. Two days later the combined strength of English and Danes fell on the city. They stormed both wooden castles, slaughtering the Norman-Flemish garrisons, keeping only Gilbert de Ghent and William Malet with his family for hostages. Waltheof's part in the slaying was celebrated by an Icelandic skald , Thorkell Skallason and was recalled much later by the Anglo-Norman scribe William of Malmesbury: 'he singly killed many Normans in the battle of York, cutting off their heads one-by-one as they fled through the gate'.

The coming of the Danes also heralded a series of revolts in the south and west. Exeter was attacked by men from Devon and Cornwall, and the men of Somerset and Dorset laid siege to Robert of Mortain's new castle at Montacute. There is no reason to suppose a nationwide rising followed, as it is clear much of the south-west stayed loyal to the king. The siege of Montacute was raised by Geoffrey de Mowbray, bishop of Coutances, who was probably port-reeve of Bristol at this time. He had with him a force of men from Winchester, London and Salisbury. Exeter was defended by its burghers as well as by the castle garrisons who drove the attackers into the arms of the Norman force sent to relieve Exeter, led by William fitzOsbern and Count Brian of Brittany. An attack on Shrewsbury was more serious, launched by Eadric 'the Wild' and the men of Chester in alliance with Prince Bleddyn of Gwynedd. Between them they burnt down the town but could not take the castle and moved on to Stafford..

Next: 7 Hereward's Rebellion

Ann Williams' treatment of the subject of rebellion against William is slightly different, some sources and references are common, others not. As with Peter Rex, the treatment of the rebels is sympathetic. It's a difficult choice... I bought them both.

Delve into early mediaeval England...

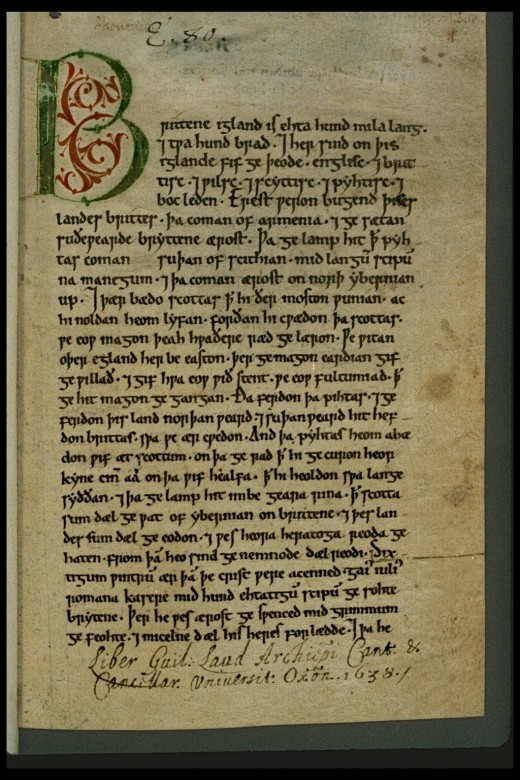

Read the continuous accounts of kings, kingdoms and wars within the land we now call England and her neighbours, Ireland, Scotland, Wales and how their history impacted on ours through the eyes of the scribes at the various religious centres of Abingdon, Canterbury, Peterborough, Worcester and York.

Accounts were begun variously at places of learning after Christianity was adopted first by King Aethelberht of Kent and progressively through the different kingdoms. Interruptions came about with the Danish and other Norse raids, occupations and reverses of belief (as when Penda became king of Mercia, the Danes and Norse takeover of York, and when Sigeberht of the East Saxons reverted to the old beliefs after his father Saeberht died. Saeberht built the original church where Westminster abbey now stands). Bishop Asser and King Aelfred ensured the Chronicles were resumed in Wessex after their wars with the Danes. Worcester, within Christian (western) Mercia continued its chronicle. Eastern Mercia found itself in the Danelaw after Aelfred's treaty with Guthrum (Wedmore, AD878).

After Aethelstan's overthrow of the ex-Dublin Danish king Sigtrygg 'Caech' ('Squinty') in the 10th Century, chroniclers re-commenced writing in the former Danelaw centres around Peterborough. The Perborough Chronicle (E) continued being written after the Conquest, well into the 12th Century until the time of King Stephen's death in 1154, marking the change through the use of the vernacular from the Old English to Middle English, the only centre to use English in the written version.

However, Norman lawmakers and their scribes had to refer back to the Old English laws and writs from before William's reign in order to maintain continuity.

Introductory page to the Chronicles

© 2011 Alan R Lancaster