- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

Sword-Flash 1066 - 2: Halley's Comet and the Brightly Lit Omen - "...the Long Hair'd Star..."

The omen taken amiss in England was read differently across the Channel

Not long after Easter, on April 24th 'the long hair'd star' was seen over the kingdom.

This was Halley's Comet, and the sight of it was taken as an ill omen for Harold's reign. There were those within the kingdom who saw him as a usurper even though the Witan had granted him the kingship (even those of the bloodline of Cerdic had to submit themselves to scrutiny by the council of earls, bishops, shire reeves and thegns). There was after all the aetheling Eadgar, grandson of Eadmund 'Ironside' and the childless old king Eadward's young kinsman.

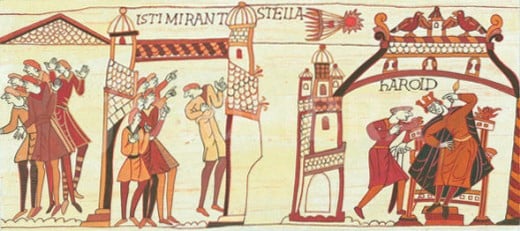

The comet came close to earth at this time and was noted throughout the known world. John of Worcester wrote of it shining 'with exceeding brightness'. The embroiderer of that particular panel of the Bayeux Tapestry showed it large and striking. Seen in England for a whole week, the comet struck fear and awe into the broad masses.

Such sights were linked with disasters - with hindsight you could say it foretold the end of Harold's reign. For the time being it heralded the return of Tostig from Flanders with ships and men provided by his brother-in-law Count Baldwin. He landed first on the Isle of Wight in May, taking silver and supplies from the inhabitants in the same way his father had done fourteen years earlier. He may even have swelled his ranks from those who lived on his estates and sympathisers who thought his cause worthwhile. He raided along the South Coast to Sandwich.

However, the welcome Earl Godwin met there did not materialise for Tostig. His lands in the area were smaller and more scattered than Harold's, and as he had been ruling in the north for the past decade, loyalties in Kent had become divided. What he achieved at Sandwich was the recruitment of a few extra hands. Harold was in London after the Feast of the Finding of the True Cross on May 3rd when news reached him of Tostig's acitivities. He mobilised a large ship and land levy and when Tostig heard they were on their way he sped away again. No support was forthcoming from the southern shires and he could not hope to face down his brother's force. He turned for the East Anglian coast, hoping to rally support from his brother Earl Gyrth there.

Realising that the winds may be favourable for a Norman invasion Harold amassed the fyrd on the south coast facing Normandy and alerted his fleet to be ready to throw back the duke's invasion. After Gyrth rebuffed Tostig's overtures, the area around the mouth of the river at Burnham in Norfolk - part of Gyrth's earldom of East Anglia - was raided but Tostig was driven off by the fyrd here with heavy losses. He next entered the Humber with sixty ships and ravaged Morkere's earldom on lands that had earlier been his, but the brothers - earls Eadwin of Mercia and Morkere of Northumbria - rebuffed his raiders energetically. Deserted by many, Tostig fled wirh only twelve ships to Scotland where he stayed during the summer, seething about the losses and desertions. He had threatened the kingdom and been repelled 'with his tail between his legs'. Without more outside help Tostig was powerless to do more. However King Maelcolm was unlikely to help him against his able brother.

Harold had made ready on the Isle of Wight for an invasion from Normandy, his earls and thegns having dealt with Tostig's 'side-shows'. William's was a much more serious threat than his brother's. The English fleet would have been led by Eadric 'the Steersman', said by Domesday to be 'rector navis' - commander - of the king's ship, and organised by Abbot Aelfwold of Saint Benet at Holme. Both these men went into exile after AD1066 because of their support for Harold. It may be at this time that the king commandeered the estate of Steyning in Suth Seaxe (Sussex) from Fecamp Abbey to use as a forward command post. In June, AD1066 William promised he would restore the property if he was successful in his bid for the crown. Other lands held by Fecamp Abbey - such as Rye - in the coastal area were not taken. Harold also sent spies across the Channel to learn more about William's preparations, and about when the crossing might be made. He was not going to be taken off-guard.

His spies would have told him that William was making plans, but also that the duke faced an uphill task in talking his vassals into the invasion. They knew a large fleet was called for, and that any crossing would be risky, let alone the potential hazards of being isolated in a foreign land surrounded by hostile forces. That William finally won them over says a lot for his own diplomatic skills and enthusiasm. He promised land and wealth beyond what they could hope for in staying put in Normandy. Earldoms were dangled for those closest to him, translated for their benefit as 'counties'.

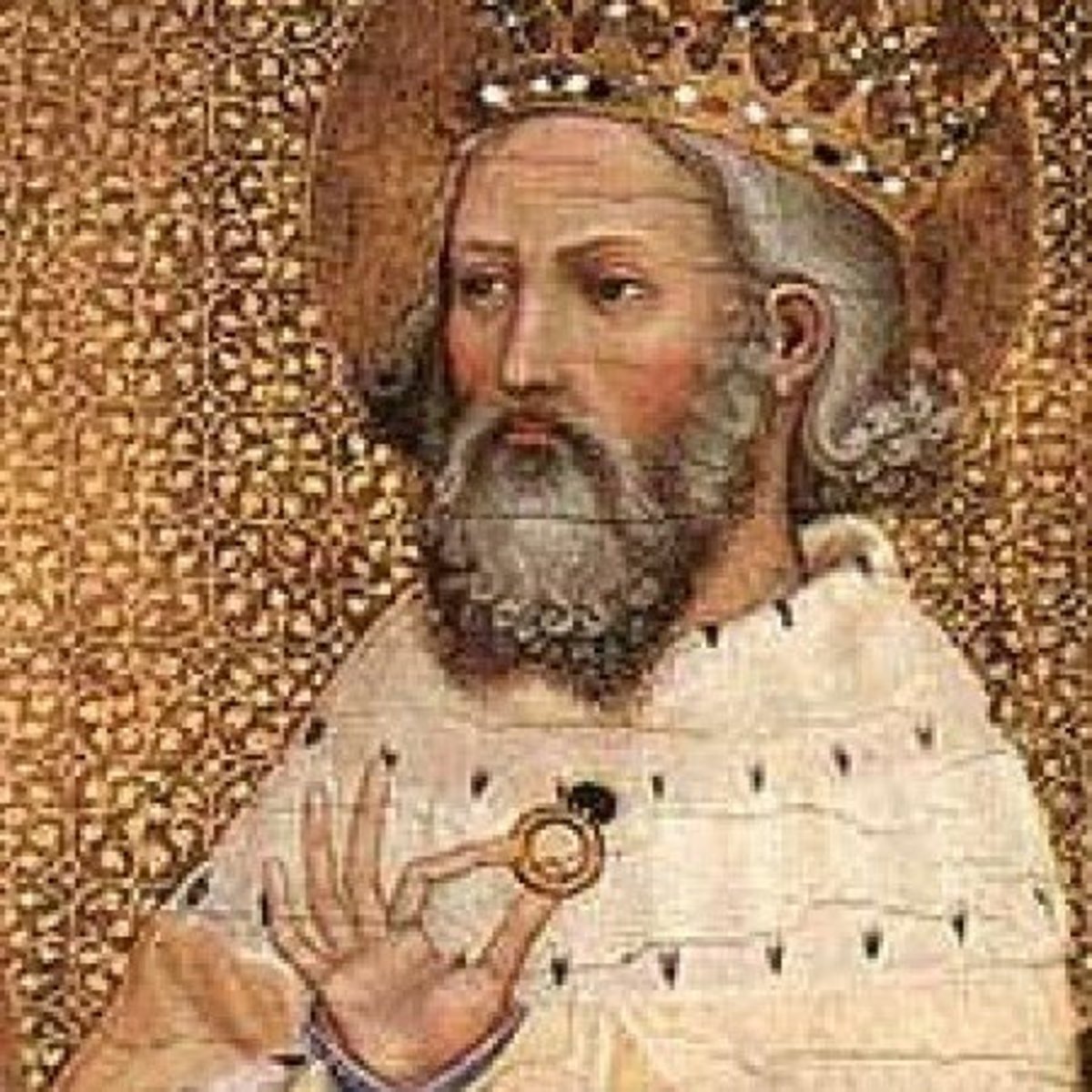

Philip I, the young king of the Franks who was under the tutelage of William's vassal Baldwin of Flanders was also won over, to provide men and materials for the venture. A bid to secure support from Rome was not altogether successful, but William put about that it was. The pontiff had nothing against the English or their Church, and had sought not to offend King Eadward in AD1062 when a papal legate was asked not to depose Stigand from his archbishopric, despite his not having his pallium.

Here in England Harold had to stand down the fyrd after a four month long watch. Contrary winds still held William back from setting sail, even were he ready at the end of summer. He considered that for a crossing of that distance the late winds would be rough in the Channel for the Normans, who had largely forsaken their Viking heritage. Once the fyrd had been stood down on September 8th he rode overland to London, the fleet rounding the eastern Kent coast on their way back to the mouth of the Thames. Many of the ship-fyrd returned to their tasks ashore on the way, such as fishing and trading - both on inland waterways and across the Channel.

Mention is made in Domesday of Aethelric, 'who went away to a naval battle against William', which may mean a pre-invasion clash at sea. But no such battle is recorded elsewhere. A fight may have taken place on September 8th, with William leading a sortie out from the River Dives after Harold's return to London. It may also shed some light on losses suffered on both sides and William's withdrawal to Saint Valery. It is still guesswork, nevertheless.

By early to mid-September Harold was back in London, readying himself for the Feast of the Exaltation of the True Cross on September 20th. With the fyrd being stood down, adverse weather conditions in the Channel and Tostig elsewhere, it must have looked as though any likelihood of invasion had ebbed - at least for another year. Had Harold's spies told him of William's failed attempt to cross the Channel with his great fleet? The chance clash in mid-Channel - especially with the losses hinted at, had it happened at all - would have given the king assurance that any Norman landings on the south coast were off.

What his spies could not tell him was who would cross the Channel from further north of Normandy, from Norway.

Next - 3: Hardradi, The Hammer Strikes

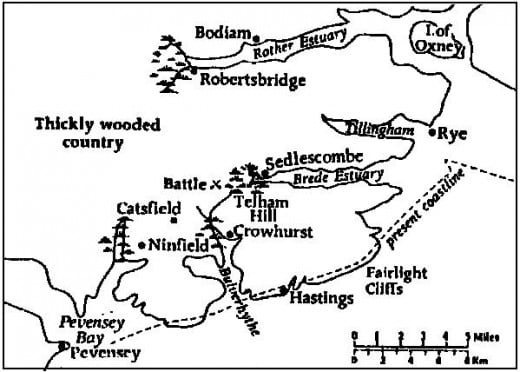

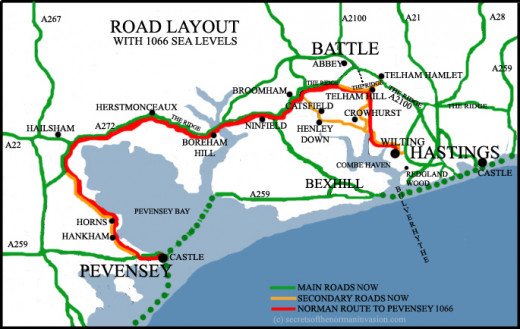

Peter Marren's book takes you from the rout of Earl Morkere's select fyrd at Gate Fulford (south of York near the A19/A64) east to Stamford Bridge. Here Tostig and Harald Sigurdsson had the shock of their lives when Tostig's older brother King Harold showed with an army drawn from the eastern shires (when all they expected was hostages and gold from York). On to the south where Harold hoped to do the same to William - the duke was forewarned, however...

Harold's fall on Caldbec Hill was not the end...

As many historians have baldly stated, with Harold went the flower of the Anglo-Saxon nobility. Less than a third of the nobility went to fight beside the king on 14th October, 1066. Most were out of reach of his messengers, or were only on their way to answer the call when they learned of his defeat.

William might have thought everything was done and dusted. He rode to London with a large contingent (500-600) of mounted knights, probably expecting a welcome with open arms. What awaited him was a welcome, but not a warm one. Armed men awaited him at London Bridge, led by Harold's stallari or marshal Ansgar, shire reeve (the orgin of sheriff) of Middlesex and the aetheling Eadgar. Ansgar had survived Harold's defeat, brought back wounded. Possibly also Harold's nephew Hakon survived (in Peter Marren's book "1066 The Battles of York, Stamford Bridge and Hastings" there is a question mark against his name in the list of participants, suggesting he could well have been rescued).

The account in the Chronicle is a bald statement:

"Archbishop Ealdred (of York) and the ealdormen of London were then desirous of having the aetheling Eadgar to king, as he was one of them; and Eadwin and Morkere promised them that they would fight with them. But the more prompt the business should ever be, so it was from day to day the later and worse; as in the end it all fared. This battle was fought on the day of the Pontiff Calixtus; and William returned to Hastings, and waited there to know whether the people would submit to him ..." .

Not much detail there then. In RAVENFEAST I have made a whole chapter from the battle, including a parley with William, as may well have taken place first. The duke was unaware of the depth of feeling against his kingship, and a shieldwall in Southwark would have been the last thing he expected to see. Several charges cost him many knights and he withdrew back into Kent licking his wounds.

He razed around the southern shires, destroying crops, crossing the Thames upriver of Reading as all the bridges that far were well defended. The Witan met him at Berkhamstead - Archbishop Stigand had already met him at Wallingford, frightened of losing lands and status - and thus Eadgar was abandoned, passed over again within a year.

However, even after William's coronation on Christas Day there was resistance. He withdrew to Barking Abbey and made ready to return to Normandy early in 1067 with his trophies - the crown jewels he mistakenly took to be his personal property as well as the young earls Eadwin, Morkere and Waltheof and Eadgar. Before leaving he had raised Copsig to the earldom of Northumbria. Copsig was Tostig's unpopular tax collector. Copsig was beheaded at Newburn-on-Tyne by Osulf after trying to flee from the feast laid on in his honour. In the west a rising by Eadric 'Cild' - allied to Welsh princes Bleddyn and Rhiwallon - saw Earl William fitzOsbern's wooden castle at Hereford burnt down. Exeter closed its gates to William later the same year and he laid siege to the city, hoping to lay his hands on Harold's family - his sons, daughters, his mother Gytha and Eadgytha 'Swan-neck' - and hanging many of the defenders when they yielded. Harold's family slipped the net. More risings followed. William's next earl in Northumbria, the Fleming Robert de Commines and his men were killed at Durham in the summer of 1068 despite warnings by the bishop of their riding roughshod over the people. York's two wooden castles - either side of the Ouse were burnt down soon after a short battle and William raced north to deal with the insurgents. They had gone, and took the castellan Richard fitzRichard with them as hostage. He appointed another Fleming Gilbert de Ghent as castellan at York, under shire reeve William Malet. With the Danes led by Jarl Osbeorn in the summer of 1069 a large force of Northumbrians took York's rebuilt castles, hoping to install Eadgar as king - at least in the North. That came to nothing and William had much of the region burnt and the population run off the land, with their livestock slaughtered. The harrying of the North saw much of Cheshire, northern Lincolnshire, Shropshire and large tracts of Yorkshire rendered unfit for tax purposes.

This was still not the end. Another rising saw Peterborough Abbey sacked. The Danes - this time led by King Svein himself with a large fleet and army, Osbeorn being disgraced for accepting a bribe by William in return for leaving him in peace - were again bought off by William and they sailed with their booty, leaving Hereward and a large contingent of Englishmen and Anglo-Danes to their own devices. Hereward turned the Isle of Ely into a fortress of sorts and a Norman siege was held off through the winter of 1070-71 until one of the monks showed William in by a little-known track onto the island.

Hereward and his closest friends slipped William's net, Morkere and several nobles were imprisoned. There was still 'guerilla' action around the kingdom, Hereward and friends only leaving England after hiding in midland forests. This is where we hear of the 'green men' (you've noticed the pub signs up and down in rural England, 'The Green Man') came into their own. You had the disinherited, the outlaws and the disenchanted banding together in the many large areas of woodland, such as the 'Shire Wood' in northern Nottinghamshire and southern Yorkshire. The Normans, their Angevin and Plantagent successors had the headache of these outlaws until at least the years of the black Death in the reign of Edward III.

As for Hereward and those who followed him into exile, many went on to fight the Normans in the eastern Mediterranean within the ranks of the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine emperors John, and Alexios Komnenos. More on them elsewhere...

There were changes afoot, and changes to come

© 2012 Alan R Lancaster