The Teacher Pay Cliques and Their Proposals

If the teacher pay debate were a high school cafeteria, there would be only two tables.

At one, you’d find the accountability clique – high-achieving honors students with no real-life skills, who think the difference between going to Harvard and working at McDonald’s is a test score. At the other table, you’d find the labor clique – hip teens quick to organize flash mobs around the latest trends and movements, caught in a vicious cycle of spending their parents’ money on the latest fashion and wondering why all the money is gone.

Replace teens with adults, tables with viewpoints, and you’ve got the teacher pay debate. Each clique has its own “solution” to the teacher pay problem: the accountability clique has rallied behind pay for performance – paying teachers based in part on their students’ academic achievement – while the labor clique tends to prefer across-the-board raises – increasing the salaries of all teachers.

But what even is the “teacher pay problem”? What would an effective method of paying teachers look like? I’m a new math teacher, and while I surely can’t speak for all teachers, there are four things I know I want from my job:

-

Autonomy: the ability to make decisions about my own career, such as moving between districts or states, without fear of losing things like tenure or half my retirement benefits.

-

Financial security: having enough money to buy necessities and save for long-term goals.

-

Respect: the sense that my time and work are valued (and compensated accordingly).

-

Professional opportunity: rewarding chances to take on more responsibility in teaching, leadership, curriculum, or other areas – while also remaining a teacher.

I like to abbreviate this list as AFRO: Teachers need Autonomy, Financial security, Respect, and professional Opportunity. (Incidentally, does anyone agree with me that “Bring back the AFRO” would be a fantastic teacher pay slogan?)

When marketing their plans, the accountability and labor cliques certainly talk about these four issues. However, neither pay for performance nor across-the-board raises truly addresses them – and, I argue, they were not designed to. Instead, the clique leaders define the “teacher pay problem” (and its solution) as whatever fits their clique’s organizational goals and narrative best. Furthermore, each clique benefits from painting the other as a villain, preventing the teacher pay debate from ever reaching a satisfying conclusion.

This is part one of a two-part blog series. In this installment, we’ll explain how teachers are paid, and profile both cliques – who they are, what narrative they live by, how they plan to “solve” teacher pay, and why I feel their “solutions” miss the mark. Next time, I’ll talk about why the AFRO went out of style – and my proposal to bring it back.

How teachers are usually paid

Before we dive into the cliques, let’s get a quick overview of how teachers are usually paid.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020), K-12 teachers made a median of $56,790 per year in 2018. However, your actual salary – as well as how much you can buy with it – will vary widely. You could be wealthy in Michigan and poor in Hawaii doing the same work.

Public school teachers don’t generally meet one-on-one with the principal to ask for a raise. Instead, they’re usually paid based on tables like this:

Years of experience

| Bachelor

| Master

| Doctorate

|

|---|---|---|---|

0

| $35,000

| $38,500

| $41,030

|

1

| $36,000

| $39,600

| $42,130

|

2

| $37,000

| $40,700

| $43,230

|

3

| $38,000

| $41,800

| $44,330

|

4

| $39,000

| $42,900

| $45,430

|

5

| $40,000

| $44,000

| $46,530

|

...

| ...

| ...

| ...

|

24

| $50,000

| $55,000

| $57,530

|

≥25

| $52,000

| $57,200

| $59,730

|

Simplified North Carolina salary schedule

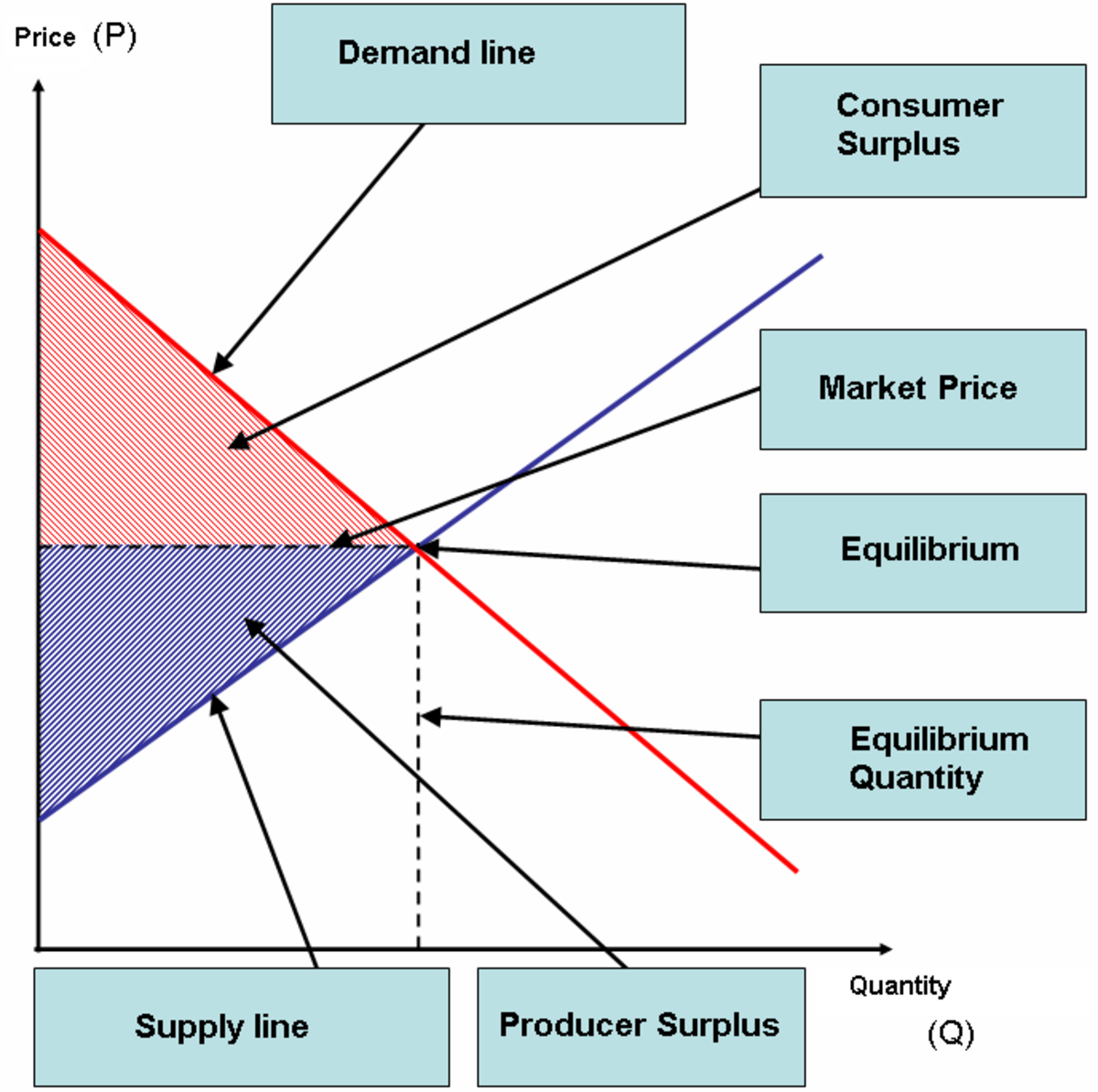

In other words, teacher salaries normally depend on only two things: level of education and years of experience. The actual numbers in this table are negotiated by the teachers’ union and the employer (usually a local school district).

Depending on your perspective, this pay scheme might seem like the peak of justice or the depths of evil. On one hand, a black female teacher might take comfort in the certainty that she’ll be paid the same as a white male with equivalent education and experience. On the other hand, she might be disheartened that she’ll be paid the same regardless of how she performs.

The accountability clique

Membership

You’ve seen them in spirit, every time you or your kids have taken a standardized test. You’ve seen them in the opinion pieces, proclaiming that the education system is broken and the U.S. is falling behind other countries. You’ve seen them leading our country, like President George W. Bush (second from left in the MeanGirls image) who signed the No Child Left Behind Act. Folks, welcome to the accountability clique.

While you probably know President Bush, perhaps you’re less familiar with Michelle Rhee (third from left), the former Chancellor of DC Public Schools who fired 270 teachers, 100 district bureaucrats, and 36 principals in her first year-and-a-half – including the head of her daughters’ elementary school. Or Joel Klein (first from the left), who spent eight years heading the New York Department of Education. These were the big names in the early days of the accountability movement, and the aftershocks of their work still reverberate today.

You can also find these guys in certain think-tanks such as the American Enterprise Institute and non-profit foundations such as 50Can.

Their narrative

The accountability clique believes that America’s schools are underperforming, and the solution is to hold teachers and other educators more accountable (hence the name) for student achievement. Many of their policies are designed to reward and punish teachers, administrators, and/or schools based on how students perform.

The first stirrings of the accountability clique began with a Department of Education report titled “A Nation at Risk” (Gardner, Larson, Baker, & Campbell, 1983); see cover above. Jal Mehta (2013) has written an excellent piece on this influential report and its continuing impact on American education.

Their plan

The accountability clique’s solution to the teacher pay problem is pay for performance. It’s exactly what it sounds like: pay teachers based on how well they teach, measured by some agreed-upon criteria. Here is Robin Chait explaining the federal government’s Teacher Incentive Fund, which is a grant program to encourage pay for performance (just watch the first 30 seconds):

My critique

First, credit where it’s due: from a policy standpoint, I don’t think pay for performance itself is a terrible idea. In practice, teachers stand to gain or lose maybe $3,000 – less than 0.9% of even their lowest salaries – and rewarding workers based on the value of their work is a useful economic practice. Nor does such a system have to be entirely test-based. The Teacher Advancement Program (TAP), a pay-for-performance scheme often implemented with TSL grant money, employs classroom observations and student test scores to determine bonuses.

However, it is disingenuous to frame pay for performance as a “solution” to the teacher pay problem. It’s a way to raise test scores – the Bushes, Rhees, and Kleins of the world should just own that. A $3,000 bonus is not going to provide teachers with autonomy, financial security, respect, or professional opportunity. In fact, when the first pay-for-performance schemes were implemented, many teachers were not aware of receiving bonuses (Glazerman & Seifullah, 2012). I understand why policymakers are worried about student achievement, but it strikes me as a separate concern.

The labor clique

Membership

This clique was recently on full display in St. Paul, striking at the capitol right before the coronavirus shut the schools down.

The most prominent members of the labor clique belong to the two largest teachers’ unions in the U.S.: the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). The NEA, led by Lily Eskelsen Garcia (second from the right in the MeanGirls image) is considered the more moderate of the two, having traditionally identified itself as a professional organization. The AFT, led by Randi Weingarten (third from the right) comfortably identifies as a union. Both have several regional chapters that go by various names; there are also some unions that operate independently of the two big ones.

The labor clique also has members who aren’t in unions. Some work in think tanks such as the Economic Policy Institute (EPI); others are politicians such as California Superintendent Tony K. Thurmond (first from the right).

Their narrative

Like any unions, the teachers’ unions primarily seek better working conditions, pay, and benefits for their members. Historically, they have done so by painting a sympathetic portrait of teachers and the daily hardships they face. A recent report from the EPI – remember, a labor-affiliated think tank – shows that teachers earn 21.4% less than the average college graduate with similar education (Allegretto & Mishel, 2019). The labor clique often cites the low take-home pay of teachers as a major reason for turnover and teacher shortages.

The labor clique has also collectivized teacher interests. By organizing strikes and using language like “standing with teachers”, it puts forth the image of teachers as one gigantic force rather than many distinct individuals. This is a classic union tactic which is effective at getting leaders to meet the union’s demands; it’s a lot harder to say no to a thousand teachers than to one teacher.

Their plan

The labor clique’s solution to the teacher pay problem is the across-the-board raise. Like the accountability clique’s plan, it’s a simple policy: increase salaries for all teachers. Here is a video from the NEA’s YouTube account about raises:

My critique

I have two critiques of the labor clique. The first is about its proposal, and the second is about its tactics.

The labor clique has a bad habit of not considering the larger context in which it makes its demands, and the across-the-board pay raise demanded by the NEA and AFT is no exception. As a teacher, I would love a raise. I want my financial security. But who’s going to pay for it? Districts aren’t underpaying teachers because they’re hoarding money; they would have to stop paying for something else, or taxes would have to go up. Education budgets across the country are notoriously tight, particularly in California where I was born.

You may be surprised that I, a teacher and union member, am going against the labor clique in this regard. Well, unions do not represent the views of all teachers. At meetings of the St. Paul Federation of Educators (SFPE), I often witnessed passionate disagreement. One frequent complaint at these meetings was that the SFPE would rush votes so that members who might be opposed to its proposals didn’t have time to get informed. Several of my math colleagues have expressed disappointment that the unions have morphed from workers’ organizations to lobbyist organizations, with motives outside of their members’ interests. One even skipped the most recent strike (which actually resulted in a pay cut) to coach the math team. So, to my justice-minded friends out there: you can “stand with teachers” without agreeing with everything their unions say.

Furthermore, if a union wants something that the district literally cannot fund – such as an across-the-board pay raise – what does it do? Why, start a smear campaign! Suggest that the district secretly has the money and just doesn’t care about teachers. If that doesn’t work, strike! Grind the system to a halt at the expense of students and families.

An incomplete truth

Now, I understand that strikes and smear campaigns are sometimes necessary, such as when your employer is short-changing you out of greed. However, the real issue I have with the labor clique is that the unions’ disregard for the larger context is partly responsible for the teacher pay problem. Basically, their solution doesn’t address the real reason teacher pay is so low – and the accountability clique is equally guilty of this.

There is a major hole in the stories of both cliques: neither side can explain why teachers are paid so little. The accountability clique is not really interested in teacher pay, except when it comes to increasing performance, and some members even deny that teacher pay is low (Biggs & Richwine, 2019). The labor clique’s answer – that teacher employers don’t value teachers enough – is not reflected in districts’ actual capacity to pay. District budgets have been tight for decades.

No, the real issue lies in some promises state governments made to teachers roughly three decades ago. The economic boom happening in those times is now over, and those promises turned out to be very expensive – so expensive, in fact, that districts are still taking money out of current teacher salaries and school maintenance just to pay for them.

So, why is teacher pay so low? What were those promises? How do we fix them? That is the topic of next week’s piece.