- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

The Textbook Constitution: Distinguishing Fact From Opinion

What Do You Know About the Creation of the U.S. Constitution?

view quiz statisticsDuring my career I’ve had opportunity to review several textbooks in the area of American government and United States History on the creation of the U.S. Constitution. Below, I have provided a summary of what is generally found in those texts. This essay should be of especial help to those that are trying to discern the facts from the conclusions when they read textbook information on the creation of the Constitution.

Textbooks will often mix the facts with opinions generally assumed to be true. In the section below I have organized the material, separating the facts from the opinions.

The Facts

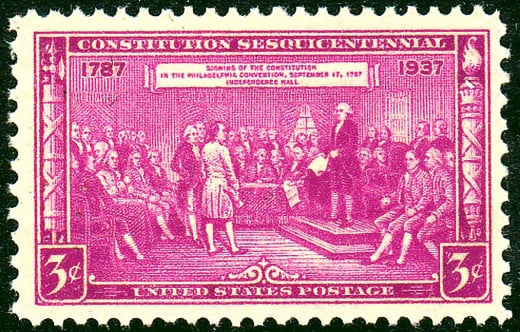

The United States Constitution was drafted at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, PA between the dates of May 25, and September 17, 1787. This was the very same building in which the Declaration of Independence had been signed eleven years earlier. Historians call this event the “Philadelphia Convention” or the “Constitutional Convention.”

Many delegates arrived late to the Philadelphia Convention for the planned date of May 14, for some because of inclement weather, so a quorum was not formed until May 25. One of the first tasks of the Convention was to elect a President of the Convention; George Washington of Virginia was unanimously elected. The delegates had been sent by their states with the charge of merely revising the Articles of Confederation. James Madison, however, believed that a stronger national government was in order, along with others like Alexander Hamilton, James Wilson, and Gouverneur Morris. Madison drafted a plan that would propose a new stronger, central government. The Plan which came to be known as the Virginia Plan or “Large State Plan” was introduced at the Convention on May 29 by the 34 year-old governor of Virginia, Edmund Randolph.

From the Convention records, much of the debate centered on the conflict between the large states and the smaller states. Larger states wanted representation based on population while smaller states wanted representation based on equal representation, much like what they had under the Confederation government. Eventually a compromise was reached, often referred to as the Grand Compromise or the Connecticut Compromise which provided for a bicameral Congress with a proportionately-based lower chamber to the satisfaction of the larger states and an upper chamber based on equal representation to the relief of the smaller states.

But large state vs. small state was not the only conflict at the Convention. Slavery was also an issue. States with large numbers of slaves wanted slaves to count in the census while other states did not. Again, a compromise was reached so that three slaves out of every five would be counted for both representation and taxation, commonly referred to as the Three-Fifths Compromise.

At times, the air was tense at the Convention. It was unusually hot that summer in Philadelphia and in order to maintain secrecy on the deliberations, they kept the windows and doors closed. This was done so that members could change their minds on proposals without appearing to be double-minded on matters. There were times when it appeared that some issues would never be resolved. For example, on the matter of who should elect the chief executive and whether he should be reelected or not was a main staple of the Convention that continued to pop up without resolution. It was not until the final days of the Convention that the delegates settled on a president to be elected by an electoral college for an indefinite number of four-year terms.

During the final days of the Convention, measures were agreed upon more quickly. On that last day of the Convention, 39 of the 55 men that attended the Convention from 12 states (Rhode Island did not send delegates) signed the document. A copy of the document was then sent to the thirteen states that were instructed to hold constitution-ratifying conventions; nine states were needed for the Constitution to take effect. This ratification process took about 2 1/2 years for all thirteen states to hold conventions and ratify the document. The first state, Delaware, ratified the Constitution on December 7, 1787; the ninth state, New Hampshire on June 21, 1788; and the last state Rhode Island ratified on May 29, 1790.

The Assumptions

Below are some of the assumptions placed in textbooks about the creation of the Constitution. This is not to say that these assumptions are not true; rather, they are not historical facts, but conclusions that need support beyond the normal support of “time, manner, and place.” Some of the assumptions are:

- that the Constitution is the result of conflict and compromise—This is not to say that there were not conflicts and compromises—there were—rather, this draws into question whether or not this should be the predominant characterization, as opposed to, say, “consensus and agreement.”

- that the Constitution reflects the interests of its framers—It was popular in early twentieth century to say that the Constitution was the product of the economic interests of its framers. This progressive interpretation of the Constitution was one of the great controversies surrounding the Constitution in the twentieth century.

- that the Constitution is a “living document” that must evolve and change with society. This assumption has become very controversial of late.

- that the Constitution was berthed out of a national crisis—John Fiske’s infamous “Critical Period of American History.” Textbooks often portray the Constitution as having arrived in the nick of time to spare the United States from civil war and economic collapse.

- that the Constitution created a strong national government

- that the Constitution was created by ideologues—some historians have portrayed the framers as men that were trying to uphold certain ideals like “equality.” This is in contrast to others who have said that the framers were highly pragmatic men who were simply trying to improve conditions without appealing to grandiose abstractions such as “equality” or “social contract.”

- that the Constitution is a “secular document,” a product of the Enlightenment--This is often assumed because many of the constitutional framers used the lingo of the Enlightenment. But it's one thing to use the fashionable terminology of the time; it's quite another to embrace its underlying principles.

Hopefully, distinguishing between the facts and the assumptions will help you the next time you read about the history of the United States Constitution.

© 2010 William R Bowen Jr

![On Principle and Pragmatism Ia - U.S. Constitutional Convention [9]](https://usercontent2.hubstatic.com/13151065_f120.jpg)