The Advantages and Disadvantages of Year-Round Schooling

Introduction

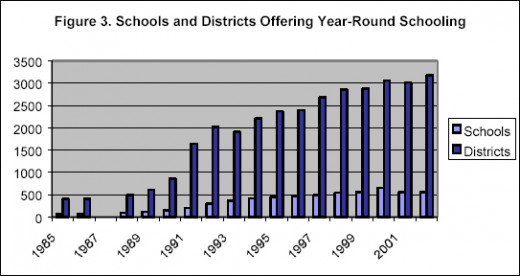

Year-Round Schools (YRS) have recently increased within the American school system. No longer are traditional schools, schools which have around a three month summer break, the only method of American schooling. There are two main types of YRS: multi-track and single-track. Multi-tracked schools are generally used to solve the problem of overcrowding by having “the student body break into three or four groups who attend school on a staggered schedule” (Von Hippel, 2007). Having groups of students go to school at different allotted times allows for the maximization of space and other resources, which is why multi-tracked schools are rather popular compared to other YRS. On the other hand, the single-track schools do not separate the student body and simply place all the students “into four, nine-week instructional blocks, with each block followed by a three-week ‘intercession’ or vacation” (Hood & Freeman, 2000). Single-tracked schools may not allow for the maximization of resources; however, they do give the benefit of a much less complex scheduling system compared to multi-tracked schools. Overall, the advantages of both types of YRS far outweigh the disadvantages, at least in comparison to the traditional U.S. school system.

Advantages in Academic Achievement

YRS bolster the academic achievement of students or, at the very least, causes no disadvantages in student achievement. The reason schools resort to YRS when overcrowding is not the issue is in order to prevent the problem of forgetting (Cooper et al., 1996). The long summer break of traditional schools has been thought to cause a disruption in the process of learning and result in a decrease in knowledge through forgetfulness. This reduction in knowledge from a lengthy summer break is referred to as the “summer setback” (Downey & Gibbs, 2010).

Studies have found that the summer setback phenomenon does actually exist (Cooper et al., 1996; Shields & Oberg, 1999). More specifically, the summer setback results in about the loss of “one month” of learning in school and, at best, some students “demonstrate no academic growth over summer” (Cooper et al., 1996). Consequently, having a large summer break could very well destroy all the learning gained from the month of May in school. However, it must be noted that this meta-analysis might not be correct. It used the standardized test scores from thirteen studies and compared them from spring to the fall of the next school year. The meta-analysis had no way of knowing exactly when the standardized tests were issued and thus does not contain consistent data across the studies it compiled.

An alternative method to studying the summer setback analyzed the learning rates of students in both traditional schools and YRS. One such study found that “children learn about as much in year-round schools as in schools using a nine-month calendar” (Von Hippel, 2007). Evidence of the summer setback still existed for traditional schools; nonetheless, this setback is the same setback acquired from the short breaks in YRS. In other words, the summer setback is a phenomenon caused from a lack of school, not from the poor distribution of school days and breaks. Thus, at worst, no significant disadvantage is acquired from YRS related to academic achievement; yet, at best, there is still the likely possibility that YRS do help academic achievement.

Advantages for Low SES and Minority Students

Although both low and high SES (socioeconomic status) students learn at about the same amount during the school year, high SES students are likely to learn more from their parents during the summer break (Downey & Gibbs, 2010). Therefore, YRS, which stop the large summer break from occurring, may end up helping the low SES students compete with the high SES students. Still, the high SES students may learn from their parents during the short breaks over YRS. This might not be the case though because it is likely more difficult for parents to find time for teaching their kids over the small breaks. Compared to when they are in first grade, by the time students are in ninth grade the learning gap between high and low SES students is tripled, “and most of the expansion in the gap has occurred during summer vacations, not during the school years” (Von Hippel, 2007). This learning gap primarily applies to reading and language skills; whereas math skills stay rather similar for both groups over breaks because parents are less likely to teach the subject (Cooper et al., 1996). Consequently, YRS can help deter the increase in the learning gap between high and low SES students, at least to some degree in reading and language skills.

The intercessions in YRS can help disadvantaged students learn material over the breaks in order to catch up to the rest of their class. Intercessions offer remedial or advanced courses in order to help students learn over the small breaks in YRS. Male and minority students are generally outperformed by female and white and Asian students in academics (Hood & Freeman, 2000). These gender and race gaps in school can be thinned by the use of intercessions because the below-average students are most likely to take advantage of such courses. Likewise, Native Americans, Hispanics, and African Americans are more likely to take intercession courses. These disadvantaged students are greatly helped by intercessions because “students who chose to take two or more intercession courses did show moderate, but steady increases in their year-to-year GPAs” (Hood & Freeman, 2000). Thus, YRS help to diminish learning gaps between different groups by offering intercessions.

Other Advantages

A multiplicity of other advantages come from YRS including less need for disciplinary actions, an increase in attendance, a probable reduction in students’ BMI, and a maximization of school resources. YRS help reduce the use of disciplinary actions because the many short breaks help tensions that develop in classrooms dissolve and not build up over time (Shields & Oberg, 1999). In traditional schools, the school days are not nearly as dispersed throughout the year, and thus problems between students from one week are likely to transfer over to the next more easily. Additionally, student and teacher attendance are better at YRS (Hood & Freeman, 2000). This could also be on account of the spread of the breaks, making everyone less inclined to burnout because there is always a break coming up soon ahead. Another advantage could be that students gain less weight in YRS. It has been found that students gain three times as much weight over the summer break in traditional schools than they do over the school year (Downey & Gibbs, 2010). Perhaps the weight gain is not as significant in YRS or at least the students are gaining weight more healthily through distributed breaks instead of gaining all the excess weight at once over the summer. A major advantage is that YRS, at least multi-tracked ones, relieve overcrowding and allow for the maximization of resources (Shields & Oberg, 1999). The school is used throughout the entire year for different groups of students at different times. Not as many textbooks need to be bought, space is more available, class sizes are smaller, and students have better access to the gymnasium, computers, and library.

Advantages in Preference

YRS may sound very beneficial in theory; however, does it appeal to the teachers, administrators, parents, and students? About 95% of the teachers prefer YRS over traditional schools and, in general, administrator do too (Shields & Oberg, 1999). Teachers reported that the YRS have benefits including “the reduction of teacher burnout, lower dropout rates, and fewer discipline problems” (Rule, 2009). The frequent breaks really help to encourage a less hostile and more involved climate in school that is beneficial in many ways. Both teachers and administrators agree that YRS help with time management and organization. The short nine week or so periods encourage teachers to stay on track more in order to finish all the material on time (Shields & Oberg, 1999). On the other hand, in traditional schools, teachers may reach the end of the school year and realize they are far behind in teaching and must resort to ignoring certain topics or cramming it all into a few weeks. Also, teachers note how they ended up working together more frequently in YRS because of the needed collaboration for organization (Shields & Oberg, 1999). Working together helps foster relationships between educators and encourages the sharing of techniques or materials that really make an impact on students.

Parents and students also give some advantages of YRS. In general, “parents of students who attended year-round schools had more favorable impressions of their school calendar” than did other parents (Rule, 2009). YRS students report more self-acceptance than do traditional school students; also, they reported less boredom, less social friction, and being more motivated (Shields & Oberg, 1999). A great amount of boredom comes to some students through the overtly long summer vacation. Students do not know how to spend all the extra time given to them all at once. Reduced social friction and increased motivation both come from the frequent short breaks distributed throughout the year in YRS because, as mentioned before, tensions drop over breaks and motivation increases because students approach each 9-week unit fresh and do not burnout as easily.

Disadvantages

Nonetheless, despite the positive reviews and advantages of YRS, it is not a perfect system. Some disadvantages of YRS are that scheduling is more difficult and that savings are not really realized. Scheduling is much more difficult in YRS, especially multi-tracked ones, because there are multiple groups that need to share the school at different times. Teachers have to change classrooms frequently, parents have to keep track of and plan ahead for their children’s breaks, and administrators have to figure out when and where to place certain groups into school without upsetting everyone. YRS entail a big scheduling mess for everybody involved. Another problem in YRS is that “cost savings are not truly realized because there are usually increased expenses for air-conditioning, maintenance, and teacher/staff salaries” (Hood & Freeman, 2000). Running a school year-round is not cheap; still, it is cheaper than creating another school to fix the problem of overcrowding.

Disadvantages in Preference

YRS are largely given support by teachers, parents, administrators, and students; nonetheless, they do note some problems with YRS. Teachers need to spend more time and energy in YRS in order to regularly change their classrooms and also communication is more complex for them (Shields & Oberg, 1999). Instead of staying in the same classroom all year, teachers need to change classrooms about every nine weeks, making the coordinating of classroom usage a big problem. Communication is more complex because not all the teachers teach at the same time; therefore, meetings are more difficult to schedule and problems take more time to be resolved. There is also the difficulty of YRS in “creating a sense of school community,” as teachers put it (Shields & Oberg, 1999). With many people on different schedules in multi-tracked schools, it is almost impossible for everyone to get to know one another. Another problem is that administrators have an increased workload due to the need for them to schedule and plan more.

Students and parents also have problems with YRS. Students in traditional schools were found to believe they had “greater autonomy,…greater overall enjoyment of school,” and teachers who individualized their instruction more than students in YRS (Shields & Oberg, 1999). But, none of these measures were found to be statistically significant, meaning that students in YRS and traditional schools do not differ too much, if at all, in these opinions. A major disadvantage for parents was the difficulty in coordinating family schedules because of YRS (Shields & Oberg, 1999). With many breaks dispersed throughout the year, it is hard to plan ahead and find daycare or babysitters for their children. Similarly, it is difficult to set aside family time; it is much easier to plan a vacation when one’s child has three months off instead of just three weeks. To sum, all opinions of YRS are not particularly favorable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the advantages gained from YRS outweigh the disadvantages caused by YRS or by sticking to the traditional school model. YRS help to prevent the decrease in knowledge from summer setback, or at the very least is not detrimental to academic achievement. YRS also help to diminish the learning gaps between low and high SES students by distributing breaks over the course of the year instead of having one big summer break. Likewise, YRS offer intercessions, which benefit the most disadvantaged students by allowing them a chance to catch up in school. With a reduction in necessary disciplinary tasks and a maximization of resources, YRS help give students more instructional time to learn and YRS reduce school costs. Another advantage is that students, parents, teachers, and administrators largely agree that YRS are better than traditional schools. Only a few problems exist with YRS: YRS are scheduling intensive, there are a lot of costs associated with running schools year-round, the coordination of resources is difficult, and there is less of a sense of community. All of these problems are inconsequential to the great advantages that come with YRS as compared to the faults of traditional schools.

Sources

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. (1996). The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: A narrative and meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 66(3), 227.

Downey, D. & Gibbs, B. (2010). How schools really matter. University of California Press, 9(2), 50-55.

Hood, S., & Freeman, D. J. (2000). Contrasting experiences of white students and students of color in a year-round high school. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(4), 349-360.

Rule, J. (2009). Year-round school calendars versus traditional school calendars: parents’ and teachers’ opinions. East Tennessee State University.

Shields, C. & Oberg, S. (1999). What can we learn from the data?: Toward a better understanding of the effects of multi-track year-round schooling. Urban Education, 34(2), 125-154.

Von Hippel, P. (2007). What happens to summer learning in year-round schools? Sociology of Education.