The American Education System: Part Two: The Age of American Unreason (A Speculative Essay)

Quick Review of Part One

Welcome to part two.

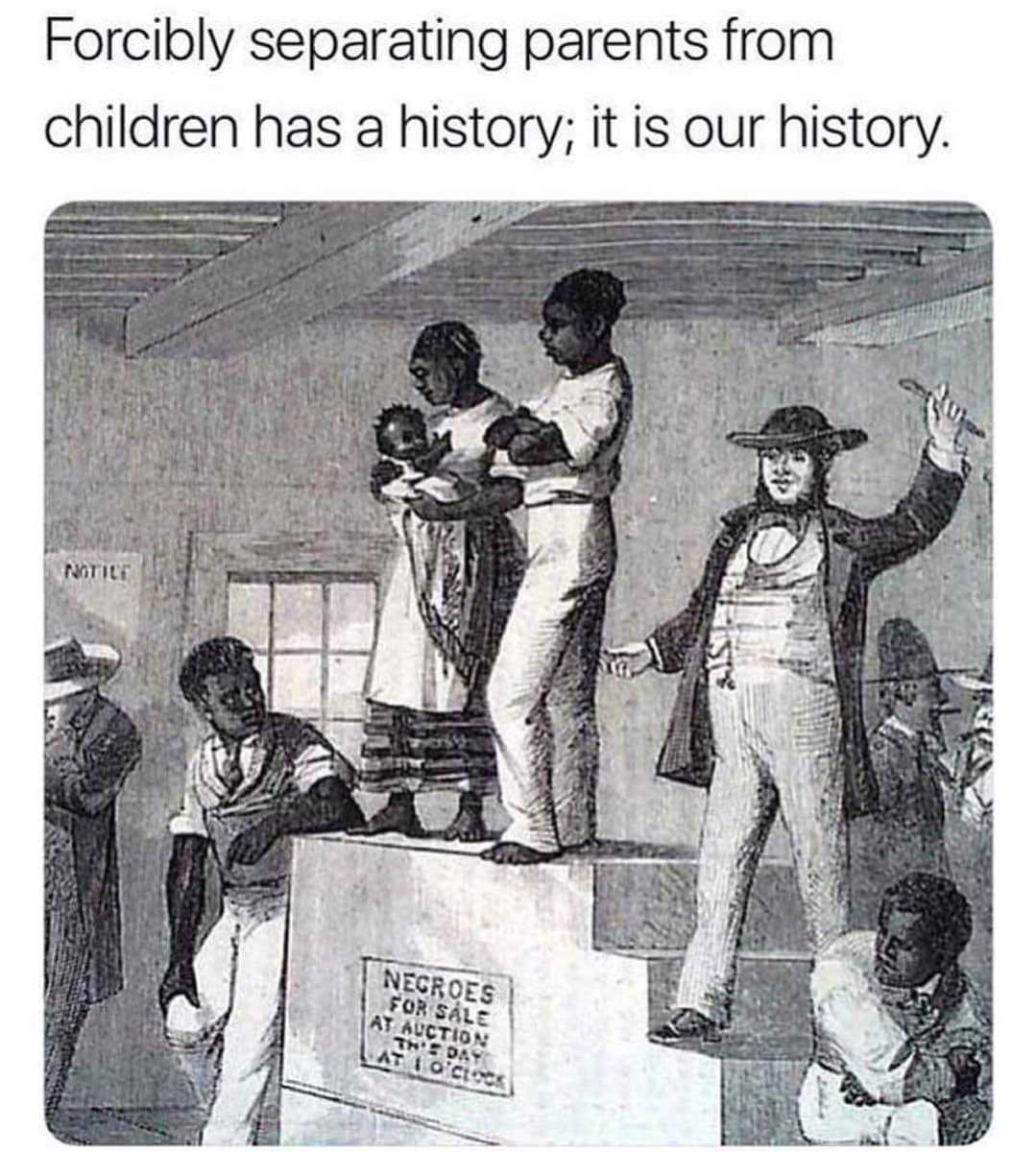

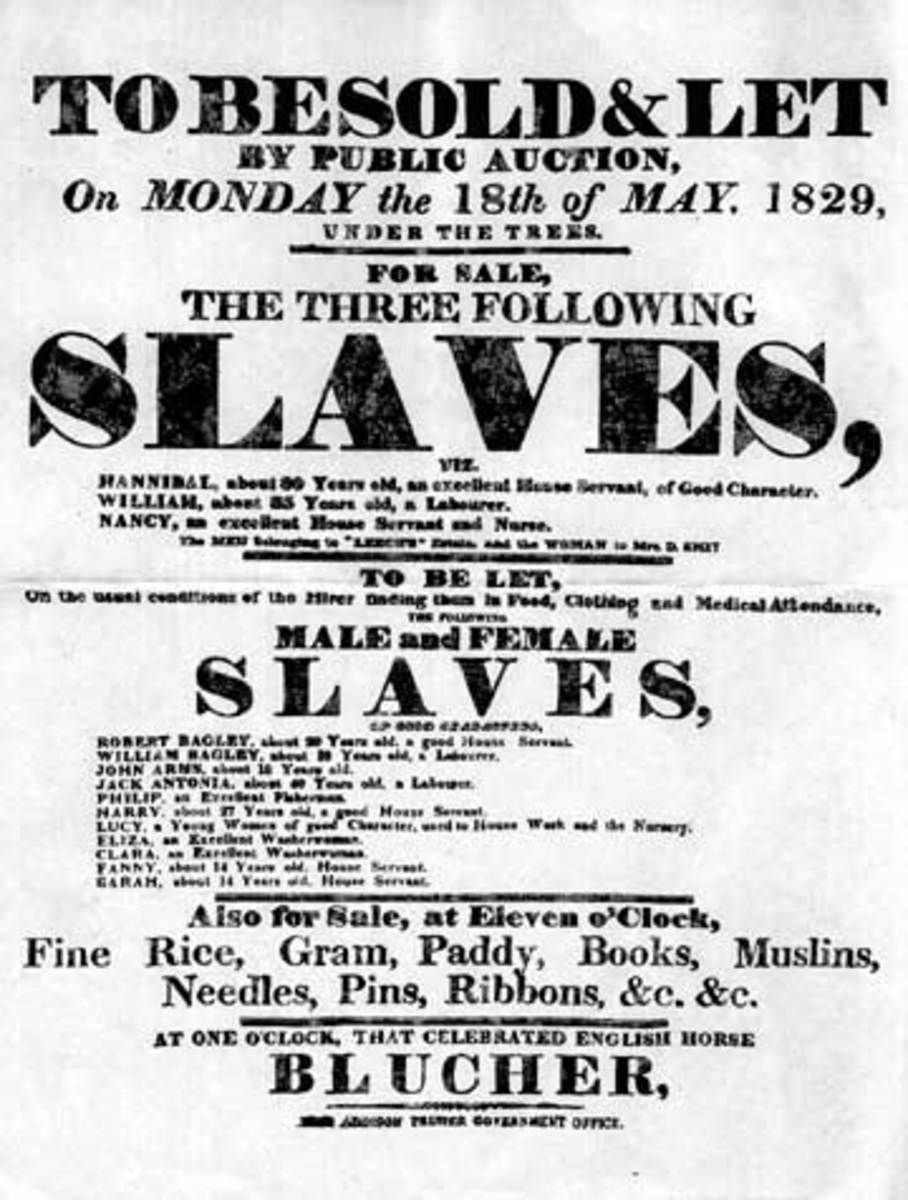

In part one I took the unusual step of beginning with the legacy of the American Civil War; or, more precisely, digging down deep into what the "War Between the States" was really all about. If you read part one, you will remember the basic conclusions I derived:

1. The American Civil War is not very well understood, even by people who think they understand it well.

2. The American Civil War of the 1860s, was about slavery. But that is somewhat misleading, because the "North" was not taking a position of "moral outrage," against the "South."

3. The North had two basic, very practical concerns: a) The South's continued reliance on slavery was blocking opportunities for free white labor; b) The South's continued reliance on slavery was blocking the industrial modernization of the United States of America as a whole.

4. White, non-slaveholding soldiers in the Confederate Army had the MOST to lose if slavery were overturned. Slavery had created a world in which even the most poverty-stricken, hardscrabble white man knew he was the social better of all blacks and Indians, and anybody else in the world, who could not be called a "white" Western European. If slavery were overturned, they would go back to being social nobodies again---or so they feared.

5. White, workaday, humble soldiers in the North had the MOST to gain from the overturn of slavery. This would mean increased economic opportunities for themselves, free white labor.

6. Big white planters in the South were not put into so precarious a position as their more humble racial brethren, because these plantation-owners were wealthy.

7. The Northern Republican industrialist or investor, who made their living from capital gains and dividends from stocks and bonds, did not have so much to gain, personally, as their more humble racial brethren.

8. Abolitionist sentiment, by and large, was NOT about liberation of blacks for the purpose of their full inclusion into American life. Abolitionist energy, by and large, was directed at either "Negro removal" or segregation.

9. Both North and South, Republicans and Democrats, pro-slavery people and abolitionists agreed on three things: a) Democracy was a finite resource; 2) There was not enough democracy to go around to include liberated blacks; 3) White Supremacy

The Age of American Unreason

I'd like to turn, now, to a book by Susan Jacoby: The Age of American Unreason, published by Pantheon Books in New York in the Year of Our Lord, 2008. Let's read inside the dust cover to see what the book is about.

"Combining historical analysis with contemporary observation, Susan Jacoby dissects a new American cultural phenomenon---one that is at odds with the heritage of Enlightenment reason and with modern, secular knowledge and science. With mordant wit, she surveys an anti-rationalist landscape extending from pop culture to a pseudo-intellectual universe of 'junk thought.' Disdain for logic and evidence defines a pervasive malaise fostered by the mass media, triumphalist religious fundamentalism, mediocre public education, a dearth of fair-minded public intellectuals on the right and left, and, above all, a lazy and credulous public.

"Jacoby offers an unsparing indictment of the American addiction to infotainment---from television to the Web---and cites this toxic dependency as the major element distinguishing our current age of unreason from earlier outbreaks of American anti-intellectualism and anti-rationalism. With reading on the decline and scientific and historical illiteracy on the rise, an increasingly ignorant public square is dominated by debased media-driven language and received opinion.

"At this critical political juncture, nothing could be more important than recognizing the 'overarching crisis of memory and knowledge' described in this impassioned, tough-minded book, which challenges Americans to face the painful truth about what the flight from reason has cost us as individuals and as a nation."

So, the book deals with the current "age of unreason," as distinguished from "earlier outbreaks of American anti-intellectualism and anti-rationalism." There's something worse about this current age of American unreason; and the American addiction to "infotainment" of various kinds, makes it worse, according to Jacoby.

Here's a juicy nugget to dig into from the introduction:

"To cite just one example, Americans are alone in the developed world in their view of evolution by means of natural selection as 'controversial' rather than as settled mainstream science. The continuing strength of religious fundamentalism in America (again, unique in the developed world) is generally cited as the sole reason for the bizarre persistence of anti-evolutionism. But that simple answer does not address the larger question of why so many nonfundamentalist Americans are willing to dismiss scientific consensus. The real and more complex explanation may lie not in America's brand of faith but in the public's ignorance about science in general as well as evolution in particular. More than two-thirds of Americans, according to surveys conducted for the National Science Foundation over the past two decades, are unable to identify DNA as the key to heredity. Nine out of ten Americans do not understand radiation and what it can do to the body. One in five adults is convinced that the sun revolves around the earth. Such responses point to a stunning failure of American public schooling at the elementary and secondary levels, and it is easy to understand why a public with such a shaky grasp of the most rudimentary scientific facts would be unable or unwilling to comprehend the theory of evolution. One should not have to be an intellectual, or, for that matter, a college graduate to understand that the sun does not revolve around the earth or that DNA contain the biological instructions that make each of us a unique member of the human species. This level of scientific illiteracy provides fertile soil for political appeals based on sheer ignorance" (1).

Here's another good one!

"The unwillingness to give a hearing to contradictory viewpoints, or to imagine that one might learn anything from an ideological or cultural opponent, represents a departure from the best side of American popular and elite intellectual traditions. Throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, millions of Americans---many of them devoutly religious---packed lecture halls around the country to hear Robert Green Ingersoll, known as 'the Great Agnostic,' excoriate conventional religion and any involvement between church and state. When Thomas Henry Huxley, the British naturalist and preeminent popularize of Darwin's theory of evolution, made his first trip to the United States in 1876, he spoke to standing-room-only crowds even though many members of his audiences were genuinely shocked by his views on the descent of man. Americans in the 1800s, regardless of their level of formal education, wanted to make up their own minds about what men like Ingersoll and Huxley had to say. That kind of curiosity, which demands firsthand evidence of whether the devil really has horns, is essential to the intellectual and political health of any society. In today's America, intellectuals and nonintellectuals alike, whether on the left or right, tend to tune out any voice that is not an echo. This obduracy is both a manifestation of mental laziness and the essence of anti-intellectualism" (2).

But wait, here's an even better one!

"If, as I will argue in this book, America is now ill with a powerful mutant strain of intertwined ignorance, anti-rationalism, and anti-intellectualism---as opposed to the recognizable cyclical strains of the past---the virulence of the current outbreak is inseparable from an unmindfulness that is, paradoxically, both aggressive and passive. This condition is aggressively promoted by everyone, from politicians to media executives, whose livelihood depends on a public that derives its opinions from sound bites and blogs, and it is passively accepted by a public in thrall to the serpent promising effortless enjoyment from the fruit of the tree of infotainment. Is there still time and will for cultural conservationists to ameliorate the degenerative effects of the poisoned apple? Insofar as the weight of one's will is thrown onto the scales of history, one lives in the stubborn hope that it might be so" (3).

I don't mean to sound like I'm teasing because I'm not. Like Bill Clinton, "I feel [her] pain." But in this series we're going to take a look at a little bit of the "best side of American popular and elite intellectual traditions." As we do that, we just might get some insight into exactly why lecturers from here, there, and everywhere could draw, in the late nineteenth century, "standing-room-only crowds" of Americans of various formal education levels; and as we do that, some light may be shed to explain what Susan Jacoby sees as the dramatic drop-off of serious public engagement with serious intellectual culture.

If you have read part one of this series, then you may suspect the direction I will be going in trying to answer the question/lament Susan Jacoby raises in her book. Does that make sense?

We're just allowing Susan Jacoby to speak for herself (I hope to provide a full, proper review of her book sometime down the road).

"One cultural development in harmony not only with Emerson's call for a new respect for learning on native grounds but also with the expanding democracy of the late 1820s and 1830s---the Jacksonian era---was the American lyceum movement,. The first community-based lyceum, established in 1826 in Millbury, Massachusetts, was intended as a vehicle for expanding the knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, of young men already employed in mills and other new industrial enterprises springing up throughout New England. Through a series of lectures to be held in the evenings, after the end of the work day, employed adults might improve on the cursory education of their youth: it was never too late to learn. The Millbury lyceum was modeled on a British lyceum established in 1824, but the American lyceum movement quickly took on a character of its own and began to reach out to all segments of the community, including women. By 1831, there were between eight hundred and a thousand town lyceums. Regardless of how few lectures were delivered in the smaller towns, that is an impressive figure for a country with a population of under 13 million at the start of the decade" (4).

We're going to have a word to say about the "best side of American popular and elite intellectual traditions" that Ralph Waldo Emerson, specifically, delivered.

Let's do one more passage.

"Middlebrow culture, which began in organized fashion with the early nineteenth-century lyceum movement---when no one thought of culture in terms of 'brows'---and extended through the fat years of the Book-of-the-Month Club in the 1950s and early 1960s, was at heart a culture of aspiration" (5).

Twenty years beyond the sixties, Jacoby says that's "all she wrote," with regard to American intellectual culture.

"In 1960, there were twice as many American symphony orchestras---1,100---as there had been in 1949. The number of community art museums had quadrupled since 1930. Recordings of classical music accounted for 25 percent of all record sales by the end of the fifties, compared with under 4 percent today" (6).

"'Art' movie houses also proliferated in the fifties; there were more than six hundred in 1962, compared with just a dozen in 1945. What sophisticate-manqué of my generation can forget the thrill of seeing a foreign movie for the first time in an art moviehouse in a small Midwestern college town? Finally, these were the years of the paperback book revolution, a development of fundamental importance to middlebrows because middlebrowism was, above all, a reading culture" (7).

Let's try this one...

"Yet even as middlebrow culture, bolstered y highbrow contributions, seemed at its most robust, it was entering a period of gradual enfeeblement fostered by social forces that first manifested themselves in the mid-fifties and became more dominant in the sixties. The most important of these was of course television, a luxury that, in the course of just one decade, came to be considered a necessity. The new medium could not corrupt highbrow culture, because there basically was no highbrow culture on the air, but it could and did help to corrupt middlebrow culture" (8).

But the damage was not immediately catastrophic. Television even tried to do some cultural good, as Susan Jacoby tells it.

Then there was a big-time quiz show scandal...

The game shows went from challenging the contestants with questions that would have, at minimum, required a wide background in reading to answer, to something less challenging in its wake.

But still, the damage was not immediately catastrophic...

"At first, the process was all but imperceptible. The precipitous decline of reading and writing skills, now attested to by every objective measure---from tests of both children and adults to the shrinking number of Americans who read for pleasure---was more than two decades away. Books still mattered enormously, not only at the beginning of the sixties but also throughout the social convulsions of the late sixties. Yet there were visible signs and portents for those able to read them. Afternoon newspapers were beginning to lose readers throughout the country, in metropolises and small towns, by the early sixties, and evening papers would be well on their way to becoming an extinct species by the end of the decade. Venerable old middlebrow magazines like the Saturday Review were also hemorrhaging subscribers, as new editors and owners tried desperately, with little success, to put a more trendy gloss on their hopelessly earnest middlebrow format and contents. Even the mass-circulation titans of the Luce empire had begun to lose ground by the mid-sixties" (9).

Okay, that's enough. We've found the question we are going to investigate. Why did this precipitous decline in reading, literacy, and intellectual curiosity about the wider world, exemplified by the collapse of reading for pleasure, take hold of middle America, starting around the mid-sixties?

Okay.

The reason I went through all of that with Susan Jacoby's book is so that we could dig up a couple of year numbers.

Let's do the numbers...

Because I like nice, round numbers, let's start with:

1820: It was sometime around that year, that Susan Jacoby tells us that the "lyceum" movement started in America.

1980: This is the year that Ronald Wilson Reagan won election as President of the United States and would formally take office the next January. But beyond that, recall that Susan Jacoby talked about how books and reading and serious intellectual culture were still enormously meaning to middle America at the start of the 1960s. Jacoby basically told us that it would take at least another two decades for all of that to go to hell in a hand basket. Remember that?

That is how I get the years 1820-1980. If I have read Susan Jacoby correctly, we should understand this time frame, more or less, as a period in which American intellectual culture was serious, meaningful, deep, and broadly participatory.

Of course we must make allowances for that fact that nothing in this world is perfect. Therefore, we should assume that between 1820 and 1980, there must have been a hiccup or two, slips and falls into darkness. But, I suppose those sojourns were relatively short-lived.

Anyway, generally speaking with caveats, I think Susan Jacoby was saying that between roughly 1820 and 1980 was a good time, culturally, to be an American.

Now then, there is something very interesting about those numbers---1820-1980---right off the bat.

Those numbers correspond almost exactly to a set of numbers used by an economist called Dr. Rick Wolf.

His numbers are: 1820-1970

Between his numbers and Susan Jacoby's, we're talking about a "give-or-take" a mere ten-year situation, yes?

And so, we're basically talking about the same period of time. Notice, one set of numbers come from the work of a cultural historian, Susan Jacoby; and almost the same set of numbers come from an economist, Rick Wolff.

The Magic Numbers 1820-1980, 1820-1970

In the wake of the financial and economic crisis that hit America sometime in 2007-8-9, Dr. Wolff started making the rounds with his analysis of where the crisis had come from and how it had developed. To do this he put the situation into a broader historical context.

What Dr. Wolff says is that America had it really, really great for the one-hundred-fifty years in question. He doesn't think any other country had ever enjoyed such a period of growth and prosperity; it is, in his view, thoroughly unprecedented, phenomenally so.

What happened?

Well, says Dr. Wolff, for every decade between 1820 and 1970, American workers enjoyed rising real wages---wages matched to the rate of inflation. There are various reasons for this. The general situation was such there was always a shortage of labor. There was always more work to do than there were hands to do it. As a result, employers basically had to pay those hands well to do it (10).

By the way, wages even rose during the Great Depression because even as wages fell, prices fell a little more, says Dr. Wolff. But in the 1970s, the situation swung around the other way such that there was now an abundance of labor. There were too many hands and too little paid labor to occupy them. Immigration restrictions were lifted; women were coming into the workforce; automation was replacing human labor altogether; and containerization made it possible to pack up the plant and relocate first to the suburbs, then to the Southern United States, then to Mexico, then to China, and so forth (11).

The United States had experienced a sweet spot 1945-1975, or thereabouts. After World War Two, the rest of the world was smashed. Western Europe and Japan could only rebuild by buying American stuff. What's more, they had to borrow American money to buy the American stuff. But in the 1970s, these countries have recovered and once again competing with the United States. The US no longer has the playing field all to itself (12).

Basically employers took advantage of this situation, in the 1970s to hold down wages, in real terms. Basically, Dr. Wolff's analysis is that working class America had been experiencing a thirty-some year financial and economic crisis due to this process. Because wages were no longer rising, workers tried some things: put more family members to work; and borrowed money (the credit card becomes big in the 1970s!). And the rest is history (13).

So, sometimes in the 1970s the good times stopped rolling!

Here's what I'm going to be arguing.

Between 1820-1970 (1980) Americans were getting something they needed and wanted from intellectual culture. It was a thing so powerful and addictive, that when they stopped getting it, the society went through something like narcotics withdrawal.

When the end of economic prosperity came in the 1970s and the United States could no longer keep it going, the mysterious X-factor that, in fact, masses of white Americans had been getting from intellectual culture, starting with the beginning of the "lyceum" movement in 1820, was no longer a sustainable assertion.

When masses of white Americans could no longer get the X-factor from intellectual culture, they turned away from intellectual culture. This, of course, means that other bases of generating a mass interest in intellectual culture must be found.

By the way, what is that mysterious X-factor?

We'll take a look at that in part three.

Thank you so much for reading!

Part Three

http://wingedcentaur.hubpages.com/hub/The-American-Education-System-Part-Three-The-Imperial-Cruise

Works Cited

1. Jacoby, Susan. The Age of American Unreason. Pantheon Books, 2008. xvii-xviii

2. ibid, xix-xx

3. ibid, xx

4. ibid, 55

5. ibid, 103

6. ibid, 105

7. ibid

8.ibid, 125

9. ibid, 127

10. I recommend viewing all of Dr. Wolff's YouTube videos, but this one should give you a comprehensive overview:

Economic Crisis and Globalization - Richard D. Wolff Lecture 4. (2012). [YouTube video]. United States.

11. ibid

12. ibid

13. ibid.