- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Napoleonic Wars: The Battle of Trafalgar

Nelson's Ship

Nelson's Enemy

Threat of Invasion

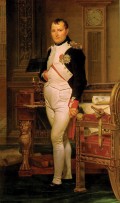

In the spring of 1805, Napoleon Bonaparte stood poised on the French Channel coast, staring across at England, just as Julius Caesar had once done, just as Adolf Hitler would do in just over 100 years time. He’d managed to assemble some 2000 gunboats and transports, all waiting to ferry some 167,000 men across the 12 miles of open water to the coast of Kent. In order to successfully invade England, Napoleon had to safely lure the Royal Navy out of the Channel, at the same time that his rather ramshackle flotilla of barges and flat bottomed boats sailed out of Boulogne and Calais.

Napoleon was first and foremost a soldier and held his navy in utter contempt, especially after their humiliating defeat at the Battle of the Nile seven years earlier. But he knew that he needed their support if he was to successfully eliminate his most dangerous foe. Napoleon however, had a rather unfortunate knack of appointing the least suitable men to the most crucial posts in his navy, and the selection of Count Pierre Villeneuve, the same man who had witnessed the L’Orient explode in Aboukir Bay was a sign that the little general had truly excelled himself. Villeneuve despised the Corsican’s personality and handling of politics, and justifiably didn’t think much of Napoleon’s abilities as a naval tactician, particularly his plan to try to lure Nelson to the West Indies, using a squadron sailing out of Toulon on the 30th March. At that time, Nelson was sailing through the balmy waters of the Mediterranean, passing between Sardinia and Sicily, in anticipation of Villeneuve electing to sail for Egypt. It took until the 18th April, for the truth to be revealed, and thus Nelson along with 10 ships of the line and three frigates struck out into the Atlantic.

On the 16th May, Villeneuve reached the Caribbean island of Martinique, where he was determined to remain until Admiral Gauteaume’s squadron, sailing out of Brest joined him. But Villeneuve was forced to set sail for Europe to support Napoleon’s landings by the 22nd June. However, his force had been bolstered by six Spanish ships commanded by Admiral Federico Gravina.

The Spanish Commander

Calder's Action

Nelson, meanwhile had arrived in the West Indies, but due to faulty intelligence headed south to Trinidad rather than north, once again the ever elusive Villeneuve had evaded him. However, Nelson’s colleague, Admiral Sir Robert Calder met with more luck when he literally ran into the Combined French Fleet at Cape Finisterre on the 22nd July. Despite Calder facing a deficiency in numbers, and a thick fog, which severely hampered his actions, he succeeded in capturing two Spanish ships and damaging four others. In return, none of his ships were sunk or captured, and only four were damaged, five days later the two opposing fleets sailed off in opposite directions.

Calder understandably thought he had done well, but faced intense criticism back home for failing to destroy the Combined Fleet. Calder even went so far as to demand a court martial in an effort to clear his name. The only consolation for the Admiral was that his French counterpart’s performance was considered even worse.

Admiral Villeneuve was equally proud and ungraciously laid the blame for the defeat at the hands of Gravina and his Spanish fleet, the truth was that the Spanish had fought bravely and splendidly; even Napoleon, a renowned Hispanophobe was forced to admit the truth about a month later.

Nelson at Cadiz

Nelson had nothing to celebrate either as he returned to England on the 19th August, expecting to suffer a shower of abuse, but was instead was universally praised, even the normally stone faced Prime Minister William Pitt afforded him his full backing. On the 29th September, the Admiral celebrating his 47th birthday took command of the British blockade at Cadiz. Despite the fact that he was still in his forties, the Admiral already had a full head of white hair, sunken cheeks, and a small, maimed body that made him look at least a decade older.

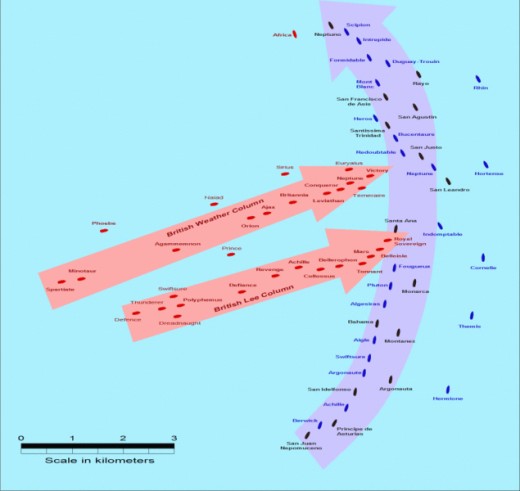

Despite his ageing features, Nelson’s fighting spirit remained strong, and his mood perked up even further, when Pitt’s promise of aid was unexpectedly fulfilled. By the middle of October, the British possessed 27 ships of the line plus five frigates. Using his new found strength and confidence, he devised a plan to attack the Combined Fleet after its departure from Cadiz in two columns at 90 degree angles to their line, with the intention of breaking it up, in order to isolate and then destroy the rearmost part before support could arrive. Nelson may have thought that he had managed to devise a brilliant plan, while Villeneuve had been left totally in the dark. But despite his timidness and his inadequacies as a leader of men, the French Admiral was definitely no fool, and his careful studies of Nelson’s tactics ensured that he was ready to face up to the challenge. Moreover, the actions to follow would serve to prove that he certainly wasn’t a coward.

England Expects...

Dispositions

The Combined Fleet departed from Cadiz during the early hours of the 19th October, but it took two whole days for them to reach the Strait of Gibraltar. The Franco-Spanish line had quickly disintegrated into a straggling scattered 9 mile line of confused ships. The early morning of the 21st would prove equally fateful for both sides, as a growing groundswell spelled the onset of a fierce Atlantic storm.

Villeneuve who had originally intended to head further into the Mediterranean suddenly ordered his fleet to reverse course, his reasoning was that he would rather meet his end in battle, rather than have to face the wrath of Napoleon should he manage to escape safely to Naples. By 10 in the morning, his fleet had formed the shape of an irregular crescent, with large spaces between each ship as they completed their about turn. Admiral Le Pelley’s division now took up the vanguard position while Gravina and his Spaniards formed a rearguard. An hour later, the British fleet was spotted; bearing down quickly on the Combined Fleet, Villeneuve observed Nelson’s fleet through his glass and noted how they advanced in two separate columns, a sign of their readiness for battle.

The British meanwhile had readied themselves for battle, some four hours before. Nelson of course, was unaware of Villeneuve’s decision to reverse course, so had readied his fleet earlier in order to try and gain ground on them, as he hoped to destroy Napoleon’s naval arm, and save Britain from invasion. At 8:40 am, Nelson and his other commanders could only gaze in astonishment as they beheld a combined fleet of French and Spanish ships heading straight for them. Nelson, as was usual style was adamant that he would take the lead in his 100 gun flagship HMS Victory, but his fellow commanders warned against such recklessness, hinting that he would become a sitting target for enemy fire. Nelson brashly dismissed the idea that he should let his deputy Admiral Collingwood’s squadron take the lead.

The winds blew west-north-west, favouring the British; high above, the clouds were grey and compact, as the distance between the two belligerents shrank rapidly. At 11 am, Nelson personally hoisted a unique, but morale boosting signal to his fleet, it simply stated: ‘England expects that every man will do his duty.’ The hoisting of the signal was met with an almighty roar of approval from both officers and men alike right across the fleet. Nelson knew that the signal had been received and understood by all.

Battle Map

A Spanish Monster

The Start of the Battle

A Bitter Fight

The End of the Battle

Useful Links

- Napoleonic Wars: Battle of Trafalgar

A very well written and absorbing account of the battle. - Broadside. Battle of Trafalgar

Another great account of the battle from a website devoted to supplying information about Nelson and his navy. - The Battle of Trafalgar

A highly detailed account of the battle packed with lots of cool pictures.

The Battle

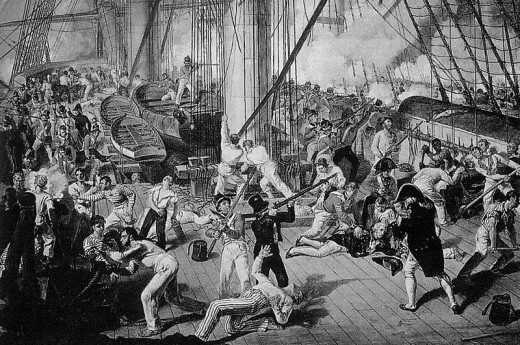

Forty five minutes later, the battle commenced as the first guns fired from Villeneuve’s ship as he gingerly hoisted his pennant. In contrast, a clearly buoyant Nelson was on the poop deck of the Victory, ordering the last signal he would give to the fleet ‘Engage the enemy more closely.’ As midday came and went, the Victory’s massive oak hull was being bombarded with shot from the Bucentaure, supported by the Redoubtable, Heroes and a Spanish monster, the 136 gun Santissima Trinidad.

While these ships fired broadsides against Nelson’s ship, the French and Spanish sharpshooters perched on the decks and masts picked off British officers and crew with musket fire. The Victory’s wheel smashed, forcing her to be steered from below deck. Nelson’s secretary John Scott was killed, most of the topmast had been shot away, and all of the other masts were badly damaged. Finally, after taking a pounding the Victory passed under the stern of the Bucentaure and unleashed a devastating volley of cannon shot that tore through the stern galleries, destroying 20 guns and killing dozens of men. The rest of the fleet followed accordingly, breaking the Franco-Spanish line just as Nelson had envisaged. Now the battle became a melee of ship to ship combat, where superior gunnery would decide the day.

An hour later, the Victory had become entangled with the Redoubtable, commanded by Captain Jean-Jacques Lucas, a fierce man, who inspired his crew to fight passionately against the hated British. In a matter of minutes, the deadly accurate French fire had wiped out 40 Marines, and a sharpshooter had hit Nelson in the shoulder, the musket ball pierced both his lung and spine.

For the next two hours the battle was at its fiercest. The Redoubtable had now come under fire from both sides, as the 98 gun HMS Temeraire joined the fight. At 1:40 pm the Temeraire raked the Redoubtable which was now a total wreck anyway, but Lucas and his proud crew refused to strike the colours until the Temeraire was in as equally poor shape as their own ship. However, exhaustion overtook the brave Frenchmen, and they surrendered reluctantly. The Redoubtable had lost 487 men, plus 81 wounded a staggering 88% of its crew.

By half past two, the giant Santissima Trinidad was also a complete wreck, but when a British boarding party stepped onto the deck, a Spanish officer calmly told them that the proud flagship had not capitulated despite the fact that it was incapable of firing any of its guns. The British eventually took the ship after two hours of dogged resistance, by which time the Bucentaure was out of commission as well, with hardly a single crew member still standing.

Admiral Villeneuve who had been standing completely still during the whole ordeal in the hope that he would be struck down, emerged with barely a scratch, when his crippled flagship surrendered to Captain Pellew of HMS Conqueror. At 4:30 pm, Nelson’s surgeon William Beatty announced gravelly that there was nothing more he could do, and the Admiral died, but not before learning that his fleet had won him a great victory. By this time, Collingwood had decimated most of Gravina’s Spanish squadron to the southwest of the main battle area. Like their French allies, the Spanish had put up a ferocious and stubborn defence of their ships, but in the end it was the British’s superior experience that won the day.

Death of a Hero

Aftermath

At the end of the Battle of Trafalgar, 17 ships of the Combined Fleet were in British hands, and another one had been reduced to driftwood. Of the survivors, four ships were captured at Cape Ortegal on the 4th November, and only eleven managed to return to Cadiz under the command of a mortally wounded Gravina. A storm erupted after the battle, forcing the British to scuttle and abandon many of their hard won prizes.

The news of Nelson’s triumph reached England on the 6th November, where the euphoria of victory and the end of the invasion threat was marred by the news of the passing of the nation’s greatest hero. The Battle of Trafalgar became one of the most clear cut and decisive victories in naval history, and heralded a century of British rule over the waves.