- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

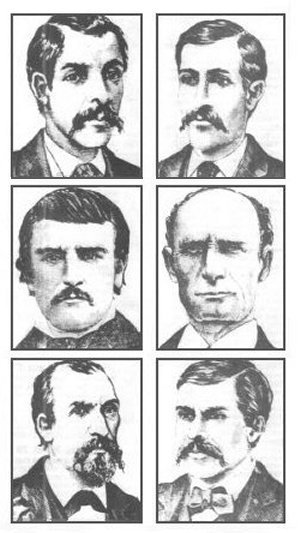

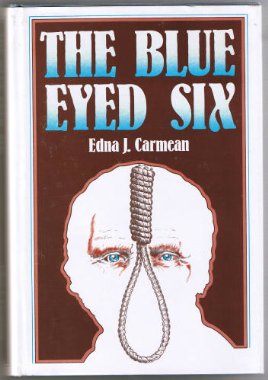

The Blue Eyed Six

Six men in Lebanon County Pennsylvania bought insurance policies on the life of Joseph Raber, an elderly recluse living in a hut in the Blue Mountains. They were betting that Raber would not live a whole lot longer and, when he died, the insurance would pay off and their financial worries would be over. However, instead of making money, they were losing money paying the premiums and they grew tired of waiting to collect. In July 1878 they decide they had waited long enough and they took matters into their own hands. The plot was common knowledge in Lebanon County and it wasn’t long before all six were arrested for murder. The six conspirators had a number of common characteristics:

- all six were illiterate;

- all six were living in poverty;

- all six were of low moral character; and,

- all six had blue eyes.

The Plan

It began with tough economic times and four men who were looking to ease the poverty in which they were living. Israel Brandt had lost an arm in a farm accident, had six children and owned the Brandt Hotel. Henry Wise was a coal miner and had seven children. George Zechman was a farm laborer and coal miner and had six children. Josiah Hummel had no children but was having a difficult time supporting himself as an unskilled laborer.

Joseph Raber was a reclusive 65-year-old man who lived in an abandoned charcoal burner’s hut in the Blue Mountains of northern Lebanon County. He lived in abject poverty; the hut had a dirt floor, the ceiling was too low for a grown man to stand up and, though he did farm labor when he could, for the most part he lived off of public charity. Raber lived with Polly Kreiser; a woman referred to as his housekeeper but in reality was probably his common-law wife.

Their plan was to take out life insurance policies on Raber. They discussed the plan with Raber and promised to take care of him if he would make them beneficiaries of the policies. Raber had no qualms about doing it.

The type of insurance they purchased was assessment insurance also known as “graveyard insurance” or “burial insurance.” The purpose of the policy was to guarantee the final expenses of the insured would be paid with maybe a little left over for the survivors. The concept was simple – the insured paid a premium to join a pool then when any of the members died, the rest of the pool were assessed a certain amount that was then given to the beneficiaries. The key to assessment insurance was that when someone died they had to be replaced in the pool. In practice it would be very similar to a pyramid scheme, with the first one out getting the most money. As time went on living members might very well opt out as they would be charged assessments as other members died.

Each of the four had a separate policy on Raber. Hummel’s policy was worth $2000, Zechman’s $2000, Brandt’s $1000, and Wise’s $3000. The problem with the plan was that while Raber was old and lived much less than an optimum life he was relatively healthy. Simply put, he would not die. The four policyholders continued to pay assessments; their plan to make money was actually costing them money. They needed to collect and for that to happen Raber needed to die.

They devised several different scenarios for murdering Raber but they abandoned every plan they came up with. They realized they didn’t have the stomach for it and would have to get someone to kill Raber for them. Israel Brandt brought his neighbor, Charles Drews, into the plot promising him $300 from each of the four conspirators if he would take care of the killing. He agreed and in turn involved his son-in-law Joseph Peters and Frank Stichler, a local thief. Peter’s rejected the offer but Stichler agreed to help for a price.

The Murder

The afternoon of December 7, 1878 Drews and Stichler met up with Raber and offered him some tobacco if he would accompany them to Kreiser’s Store and assist them. Raber agreed. The trip to the store required that they cross Indiantown Creek; the point at which they crossed the creek was bridged with two 12 inch planks. According to testimony they started across single file with Raber in the middle; at mid-point Stichler turned, grabbed Raber by the shoulders and threw him into the water. Then, depending upon whose testimony you wish to believe, Stichler held him under until he drowned, either by himself or with the assistance of Drews.

That evening Drews went to the tavern at Brandt’s hotel and told people there that Raber was dead. He told the story about the trip to Kreiser’s and the need to cross the bridge, claiming Raber had a dizzy spell in the midst of the crossing and had fallen in and drowned. The following day the coroner examined the body and declared the death accidental.

The Conspirators’ Mistake

If the men involved in the conspiracy to murder Raber had kept their mouths shut they very well may have gotten away with it. However, they didn’t. Prior to Raber’s death it was common knowledge in the area that these men held life insurance policies on Raber. They bragged about it being a smart economic move due to his age and the virtually certainty that he would not live much longer – at least in their minds. An article in the Lebanon Courier regarding the death ended with: “It is said that persons in the vicinity hold policies of insurance on Raber’s life for $13,000 upwards. There is unpleasant talk of the probability of his death not being accidental.”

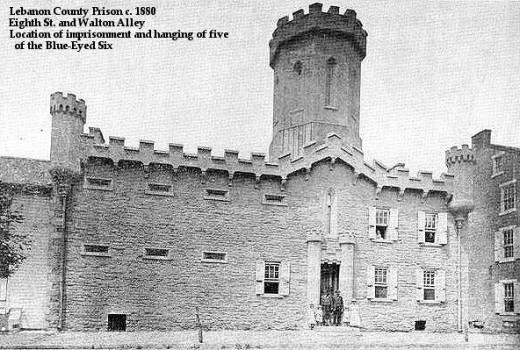

There was another issue, a personal issue that would come to play a role. While Joseph Peters was in the army he had heard rumors that Stichler was having an affair with his wife and it was well known that he held animosity toward Stichler. At the prompting of one of the insurance companies, Lebanon County constables questioned Joseph Peters regarding Raber’s death. At 4:00 a.m. on February 5, 1879, Peters admitted to seeing Drews and Stichler drown Joe Raber. That morning Israel Brandt, Henry Wise, Josiah Hummel, George Zechman, Charles Drew, and Frank Stichler were arrested for murder.

The Trial

Obviously the trial was sensational on a local level, but it even generated attention at a national and international level. It was the first time in the history of English and American law that six men would be tried together for murder. Reporters from all over the country and the world came to the Lebanon County Courthouse to witness the proceedings. The attention this trial received, up to that point in history, was unprecedented and, in 19th century terms, was on a par with the OJ Simpson trial. It was one of the out-of-town reporters who observed that all of the defendants had piercing blue eyes and came up with the moniker “The Blue Eyed Six.” This description, perhaps more than anything else, led to the sensationalism of the trial.

The trial took eight days, the longest in the history of Lebanon County. The courtroom was packed with spectators and the area between the bench and the bar was filled with tables and chairs. Designed for two-party litigation the court had to accommodate four attorneys for the Commonwealth and five attorneys representing the six defendants. There was barely room to walk between the tables.

There were a total of sixty-four witnesses called and the trial record consists of 247 pages of single-spaced typed testimony, the bulk of which was given in German, many of the witnesses were German immigrants, and translated during the trial.

Out of all the witnesses and all of the testimony it came down to one thing: would the five defense attorneys be able to discredit the testimony of Joseph Peters and his wife Lena. Peters was unshakeable; it is arguable that he bested the attorneys. When he was described as an army deserter in an effort to discredit him he vehemently denied it. He referred to himself as being on extended leave from the army, a situation that he claimed was brought about because he had heard rumors of Stichler having an affair with his wife. The defense claimed Peters and his wife were both intoxicated at the time they were supposedly witnessing the murder and that it would have been impossible to see what happened from the vantage point where they claimed to be. The jury, apparently, believed none of it. Finally, the defense asked why it had taken Peters so long after the murder to go to the authorities. He simply stated he was afraid for his life and in so doing sealed the fate of the defendants.

The jury deliberated for five hours and came back with guilty verdicts to first degree murder for all of the defendants. All of the defendants immediately appealed the verdict but only George Zechman was successful.

Zechman's involvement in the conspiracy was based solely on statements made by other defendants. There was no evidence connecting Zechman to the plot which would have been admissible in a trial of Zechman alone. On retrial in November 1879 Zechman was found to be not guilty. However, his many months of imprisonment had laid the groundwork for a respiratory ailment that plagued him the rest of his life. The local folklore attributed his painful coughing seizures to the "vengeance of the Lord" for his part in the conspiracy rather then that to an illness.

Typically executions promptly followed a jury’s verdict during this period of time; however, no one was executed in this instance until after Zechman’s trial so they could be called as witnesses.

The Executions

Drews and Stichler were to be the first ones executed and, prior to their executions, both gave full confessions. Major Henry Ernst of Harrisburg came to Lebanon as the professional executioner. The morning of the executions both men were involved with local religious folks and their families preparing themselves to die. This preparation was interrupted by Ernst so that he could measure the men. Apparently this was the first opportunity he had to perform this task and he needed to make sure the drop was appropriate. Too short of a rope and the victim slowly strangles to death; too long and the head might be severed. Neither result was considered very professional.

At 11:08 am on Friday, November 14, 1879, Charles Drews and Frank Stichler gained the distinction of being the first dual executions in LebanonCounty history.

The appeals of Wise, Brandt and Hummel were denied on March 30, 1880 and Governor Henry Hoyt fixed May 13, 1880 as the date for their execution. One week before their scheduled execution Brandt and Hummel attempted to escape from jail. After considerable effort they had managed to dig a whole large enough to crawl through in their cell wall. Much to their chagrin as they emerged on the other side of the wall they found themselves inside the jail yard surrounded by yet another wall. They were quickly rounded up and this time put into separate cells. When the appointed date arrived, the three men were hung simultaneously.

Aftermath

As a result of “The Blue Eyed Six” insurance law in Pennsylvania would change so that in order to hold an insurance policy on someone’s life there needed to be an insurable interest. In other words one would have to demonstrate a financial loss by the insured’s death such as in the case of today’s key-man insurance.

Because the case was so widely reported so was the carnival-like atmosphere at the hangings. This went on to strengthen the argument against such spectacles in the future. The case for the death penalty being used as a deterrent was also re-examined and debated and in the end retained as punishment for murder.

The conspirators thought they had planned a perfect crime. They had; they simply talked about it and their words led to their undoing.