- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The California First Nations

The Californians are as diverse as the California ecosystems

Winning the Day, Gaining Advantages and then Collapse

Most First Nations met with unparalleled catastrophe at the hand of the invaders from Europe. Some have met with extinction and others are just beginning to experience contact. But in the case of the Californians, the story, though starting in like manner as elsewhere, managed to defeat superior technology and drove the invaders back to the south whence they came and into the sea when the south route was cut off. They ended up gaining the horses left behind and this became a resource for them for warfare, transport and trade. Due to their success, the horse made its way from the west to the great plains, to the far north and this was to prove helpful to these nations in fighting the invaders as well as in the bison hunt. But the initial thrill of victory was to end in the agony of defeat as the invaders came back and in the following century, were joined by the hoards from the east in a mad rush for gold and growing space. From the south, the Spanish made another stab. From the east came ranchers, gold diggers and a rush to grab free land in some cases for people who wanted to settle. In the end, they succumbed to strange diseases brought in by the invaders. This is their story in summary and we look now at the particulars.

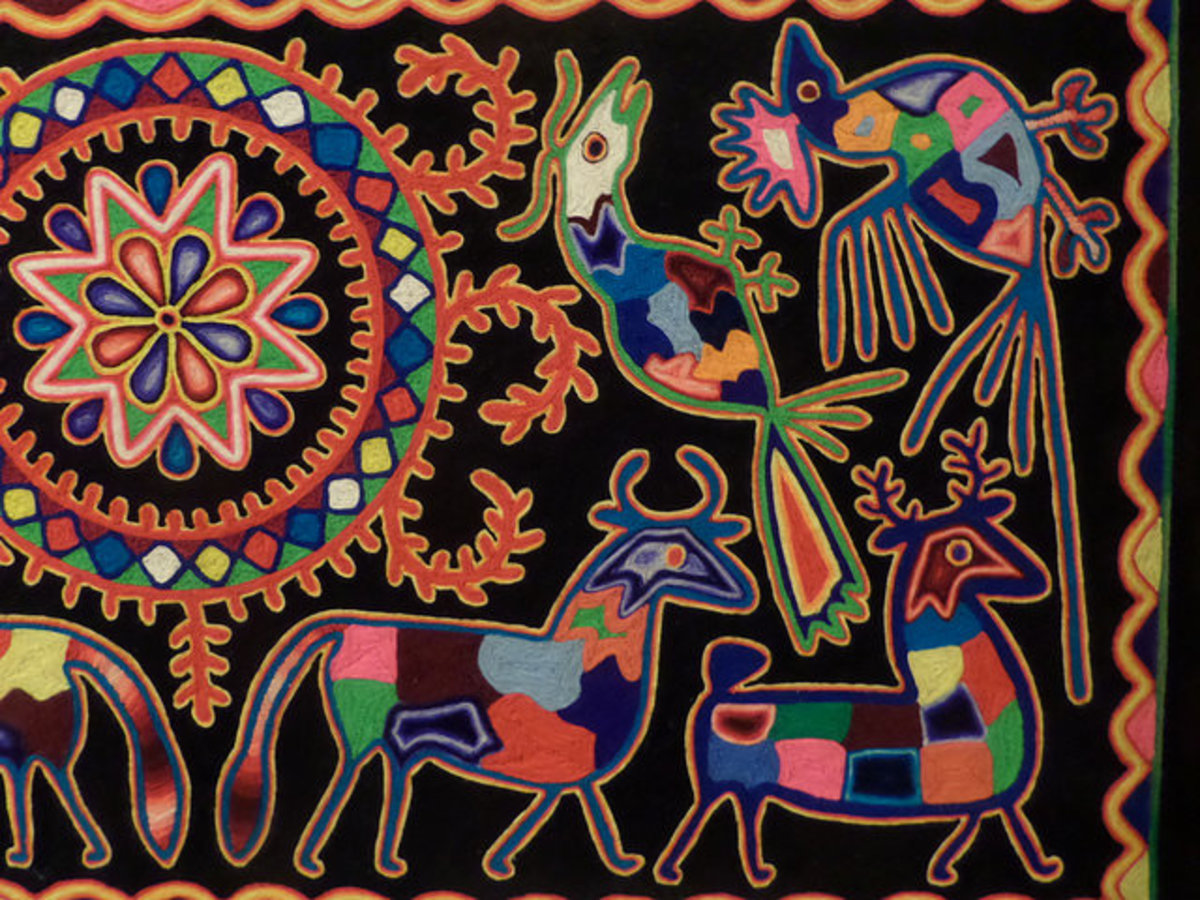

Most of the great Californian tribes lived either in the northwest of California or along its fruitful coasts where their chief foods, the salmon and acorns thrived. There was a plenitude of other wild foods as well as the extent of the region was a rich and varied eco-system. This vast region included peoples such as the Chilula, Chimarike, Hupa, Karok, the Shasta, Tolowa, Yurok, Whilikut, and the Wiyot tribes. The distinctive ecosystem of the north west rainforest encouraged these people to establish their villages. The abundant nature of the rain-forests allowed for the establishment of sedentary villages exemplified by finely crafted wooden long houses, totem carvings and large dug out canoes that would be impossible for more nomadic people. These nations thrived along the many rivers, lagoons and coastal bays that predominated the north California landscape. Even though their territory was crisscrossed with thousands of trails, the most efficient form of transport was the large dugout canoes used to travel along rivers and cross the wider and deeper ones such as the Klamath River. They used the great coast Redwood trees for the manufacture of their dug out canoes and rectangular council centers and residences. The giant redwoods were cleverly felled by these people. This was effected by a controlled burning, without setting everything else alight, at the base of the tree and then splitting the wood with driven in elkhorn wedges. Hand fabricated redwood and cedar planks were used to construct rectangular gabled homes. Baskets in a variety of designs were manufactured with the twined technique from local materials that were useful in this. Many of these arts have survived into the 20th century and traditional skills have enjoyed a great renaissance. Many assimilated tribes now produce these now popular baskets for the tourist industry.

Other nations lived throughout the western regions along the coast all the way to Baja in the south and inland to the regions bordering on the Anasazi or Pueblo nation. To the Northeast lived the Achumawi, Modoc and Atsugewi tribes. The western portion of this territory was rich in salmon and in white and red oak trees that produced acorns. There were also deer and elk in abundance. Further to the East, the climate varies from mountainous temperate weather to a high desert. Food resources found there were grass seeds, tubers and berries along with rabbit and deer. These First Nations found tule to be a useful source of both food from the root-bulb, which was eaten and the leaves a convenient material when laced together to form floor mats and structure covering. The Volcanic mountains in the Western portion of their territory supplied the valuable trade commodity obsidian. Obsidian was prized by the Aztec and Maya and much of it made its way to these nations in trade. These First Nations already had familiarity with the Mexican First Nations in trade before the Europeans arrived. This was to play a crucial role later when war commenced between them and the Spanish invaders. It was this established route that would later allow for the trade of horses to where they were needed.

The central region of California around Bear River lived tribes such as the Kato, Lassick, Maidu, Mattale, Nogatl, Sinkyone, Wailaki, Wintun, Yana, Yahi, Yuki, Pomo, Lake Miwok, Wappo, and Coast Miwok, Toward the interior were the Costanoan, Esselen, Miwok, Monache, Yokuts, Salinan and Tubatulabal nations. Vast differences existed between the coastal peoples and the nearby mountain range territories, from those living in the vast central valleys and on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. All of these nations enjoyed an abundance of acorn nuts and salmon that could be readily obtained in the waterways north of Monterrey Bay. Deer, elk, antelope and rabbit were available elsewhere in large numbers. Their world was a verdant paradise. These nations are also noted for their basketry that survived repression and is still made today.

Southern California presented a varied and unique region of First Nations and some of it was challenging. To the north, First Nations in this area are the Alliklik, Cahuilla, Chumash, Gabrielino, Kitanemuk, Luiseno, Serrano and the Kumeyaay peoples. The land and climate varied considerably from the windswept offshore Channel Islands that were principally inhabited by Chumash speaking peoples to the arid desert regions inland that bordered Pueblo territories. Communication with their mainland neighbours was affected by large and graceful planked canoes powered by double paddles, much as we can see in kayak oars. These vessels were called "Tomols" and manufactured by secretive boat making guilds of craftsmen and were manufactured to carry hundreds of pounds of trade goods and up to a dozen people. About the only rival to these canoes were the giant birch bark canoes used by the early fur trading voyagers in the Algonquin and Iroquois territories. Like their northern neighbours, the Tactic speaking peoples of San Nicholas and Santa Catalina Islands built planked canoes. They actively traded rich marine resources with the mainland First Nations. Shoreline communities enjoyed the rich animal and fauna of the ocean, bays and wetland environments. Interior nations like the Cahuilla, Kumeyaay, Luiseno, and Serrano shared an environment rich in the semi-arid Sanoran Desert life zone featuring vast quantities of rabbit, deer and an abundance of acorn, seeds and native grasses. At the higher elevations desert bighorn sheep were hunted. Villages varied greatly in size from the poor desert communities with villages with 100 people to the teaming Chumash villages with over a thousand inhabitants. Conical homes of arroweed, tule or croton were common on the mainland, while whale bone structures could be found on the coast and nearby Channel Islands. Interior groups manufactured fired clay pottery vessels, which were sometimes decorated with paint. These formed the varied nations of what was to become California and they lived largely in peace, actively trading with one another to as far east as the great plains and as far south as the Maya territory. And the trade extended well into other regions in all directions. The northernmost people also regularly attended the First Nations potlatches that occurred in the winter months and attracted large gatherings from the Alaskan panhandle to north California. Th potlatches, which they attended by paddling up in their large canoes, were held in the central territory of what is now Washington State and south western British Columbia.

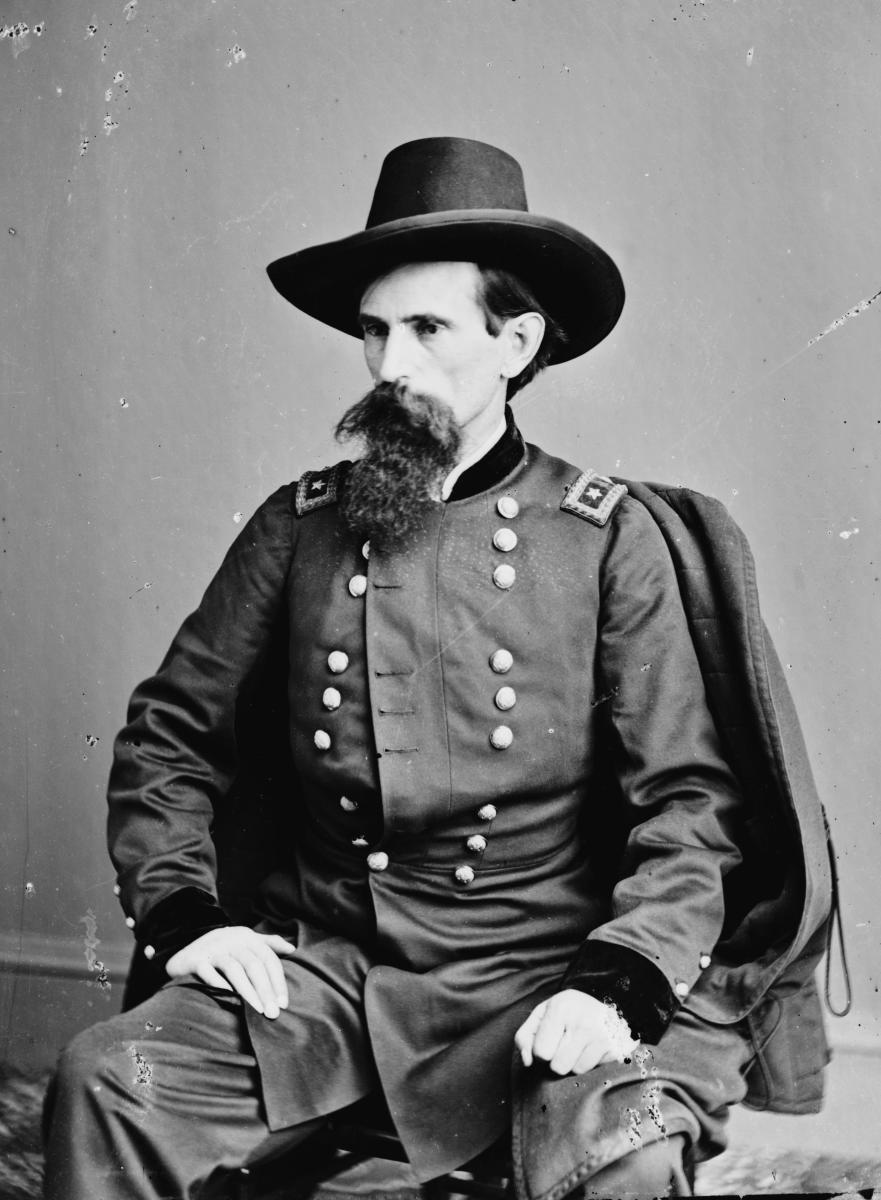

The Spanish entry into Alta California was the last great expansion of Spain's vastly over extended empire in the Americas. It was over extended due to the lack of Spanish to control such a vast territory. The small numbers were not helped when First Nations revolts decimated them. Great First Nations' revolts among the Pueblo of the Rio Grande in the late 17th century provided the Franciscan priests and monks with the arguments needed to establish missions relatively free from colonial settlers. Thus California and its Spanish colonization would be different from earlier efforts. Having learned a lesson from history, they avoided the simultaneous introduction of missionaries and colonists in their conquest schemes. The new plan was organized by the Franciscan administrator, Junipero Serra and the military authorities under Gaspar de Portola. They journeyed to San Diego in 1769 to establish the first of 21 coastal missions. Despite romantic portrayals of California missions, they were essentially coercive religious, slave labour camps organized primarily to benefit the newly established missions. The overall plan was to first militarily intimidate the local First Nations with armed Spanish might and soldiers who always accompanied the Franciscans in their missionary efforts. This was a tactic first learned at Teotihuacan and with the Inca. Simultaneously the Spanish invasion introduced European sourced domestic stock animals that gobbled up native foods, drove away the wild counterparts and undermined the free tribes efforts to remain economically independent. This was a kind of engineered famine that would later be used on the plains First Nations with far more organization and devastating results. A well established pattern of bribes, intimidation and the expected onslaught of European diseases insured experienced missionaries that eventually, desperate parents of sick and dying children and many elders would prompt frightened First Nations families to seek assistance from the newcomers as they seemed to be immune to these horrible diseases. The missions were authorized by the crown to convert the First Nations to Christianity within a ten year period. Thereafter they were supposed to surrender their control over the missions livestock, fields, orchards and buildings to the First Nations people. But the priests and monks never achieved this goal and the lands and wealth was instead stolen from the First Nations.

Epidemic diseases such as smallpox, syphilis, diphtheria, tuberculosis, influenza, children's ailments such as chickenpox and measles, and the common cold proved to be the most significant factor in the Spanish colonial efforts to overcome native resistance. These diseases caused untold suffering and misery in these communities. Soon after the arrival of Spanish colonists, the new diseases appeared among the First Nations in close proximity to the Spanish missions. Later study of demographic trends during this historic period indicate the First Nations of the America's did not possess any natural immunity to the introduced European diseases. Even before the outbreak of epidemics, a general population decline was recorded that can be attributed to the non-hygienic environment of colonial population centers. It was known from European history, that hygiene was not very good in many countries. Lack of hygiene was carried into the New World especially on the great sailing vessels where personal cleanliness among the crews was almost completely absent. These conditions including the weakening and preventable nutrition deficiency disease of scurvy on the trans-Atlantic voyages, allowed other diseases to come to the fore on the long voyages. The sick were often brought ashore for care that was considered to be more easily administered than on the ships. Some diseases such as influenza, smallpox and tuberculosis were spread on the prevailing winds to be caught by the First Nations.

A series of deadly epidemic diseases swept over the terrified First Nations populations. Beginning in 1777 a voracious epidemic possibly associated with a water born bacterial infection devastated Santa Clara Valley Costanoan children. Again children were the primary victims of a second epidemic of pneumonia and diphtheria that expanded out from what was to be later called Monterrey to Los Angeles and was recorded in 1802. The very worst of these terrifying epidemics began in 1806 and killed thousands of First Nations children and adults. It has since been identified as measles and it attacked the First Nations populations from San Francisco to the central coast settlement of Santa Barbara. The missionary practice of forcibly separating First Nations children from their parents and incarcerating children from the age of six in filthy and disease ridden gender barracks similar to residential schools to the north and east under French and English control, most likely increased the suffering and death by these epidemics. Excessive manual labour demands of the missionaries and poor nutrition contributed to the First Nations inability to resist such plagues. Less easily measured damage to mission First Nations tribes occurred as they vainly struggled to understand the biological tragedy that was overwhelming them. Faith in their traditional shamans suffered as efforts were ineffective in stemming the tide of misery, suffering and death that came of life in the missions. With monotonous regularity, missionaries and other colonial officials reported about the massive death and poor health of their Indian labourers. As much as 60% of the population decline of mission First Nations was due to introduced diseases. These facts were to be later collated in the concept of eugenics or racial hygiene.

The unrelenting virtual slave labour demands, enforced separation of children from their parents and unending physical coercion including the use of torture and sexual assault that characterized the life of First Nations under the priest's and monk's authority resulted in several well documented forms of resistance. Within the missions, the "Christian converts" continued to surreptitiously worship their old deities as well as conduct native dances. By far the most frequent form of mission First Nation resistance was escaping and going fugitive. While thousands of the almost 81,600 baptized natives temporarily fled their missions, more that one out of 24 successfully escaped the plantation like mission slave labour camps. Many Mission First Nations viewed the priests and monks as powerful witch doctors who could only be neutralized by assassination. Due to this view, several assassinations occurred. At Mission San Miguel in the year of 1801 three priests were poisoned, one of whom died as a result. In 1804 a San Diego priest was poisoned by his personal cook. In 1805, another San Miguel Yokut male attempted to stone a priest to death. Another killed a priest for introducing a new instrument of torture in 1812, which the priest unwisely announced that he planned to use on some luckless neophyte awaiting a beating.

Few modern day Americans know of the widespread armed revolts precipitated by Mission natives against the Spanish colonial authorities that had a long history of provocation. A series of battles would succeed in driving out the Spanish entirely. It began when the Kumeyaay of San Diego launched two serious military assaults against the missionaries and military escorts within five weeks of their arrival in 1769. During 1775, being desperate to stop an ugly pattern of sexual assaults, the Kumeyaay completely razed Mission San Diego to the ground and killed the local priest. Quechan and Mohave Indians along the Colorado River to the east destroyed two more missions, killing four missionaries and numerous other colonists in a spectacular uprising in 1781. This last rebellion permanently sealed off the only south going overland route into Alta California from Northern Mexico (New Spain) to the Spanish authorities. This left only the sea to escape, which some Spaniards elected to do in confiscated canoes.

Military efforts from the south to reopen the road and punish the First Nations responsible were met with total failure. The last great mission native revolt occurred in 1824 when disenchanted Chumash First Nations violently overthrew the mission control centers at Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez and La Purisima. Santa Barbara was sacked and abandoned by the Spanish while the Santa Ynez Chumash torched 3/4 of the buildings before fleeing themselves. They managed to obtain all the horses and much Spanish ordinance in the process. Defiant Chumash at La Purisima seized that mission and fought a pitched battle with Spanish colonial troops while a significant number of other Chumash escaped deep into the interior of the Southern San Joaquin Valley. After 1810 a growing number of native guerrilla bands evolved in the interior when fugitive mission First Nations allied with interior tribes and villages. They were mounted on horses and used modern weapons. They began raiding mission livestock and fighting colonial military forces on an equal footing, making the future conquest much more difficult.

The impact of the mission system on the many coastal First Nations was extremely devastating. Missionaries required tribes to abandon their aboriginal territories and live in filthy, disease ridden and crowded virtual slave labour camps. Massive herds of alien and introduced stock animals and new seed crops soon crowded out aboriginal game animals and native plants. Feral hogs that were allowed to fee range, ate tons of raw acorns, depriving even the remaining free tribes in the interior of a significant amount of aboriginal food and protein. Devastating waves of epidemic diseases swept over the terrified Mission First Nations. The shortened life expectancy of mission First Nations prompted missionaries to vigorously pursue runaways and coerce interior tribes into supplying more and more labourers for the priests and missions. Divisions and differences were fanned as some first nations would raid neighbouring tribes to capture slaves that were then traded. Missionary activities therefore thoroughly disrupted coastal tribes, and the incessant demand for healthy labourers seriously impacted adjacent interior First Nations. In 1836 the Mexican Republic forcibly stripped the priests of the power to coerce labour from the Indians. After this the missions rapidly collapsed. About 100,000 or nearly a third of the aboriginal population of California died as a direct consequence of the missions of California in the span of little more than a generation. The Spanish met their match and retreated for a while, but were to come back with assistance from the English in the East during the Indian Removal Era of 1830 to 1879.

Despite devastating population decline, many First Nations managed to maintain tribal cohesion. After 1800, most mission native populations were a hodgepodge of different tribes speaking a multiplicity of languages. Due to the fact that the First Nations refused to learn or feigned ignorance of the Spanish language, missionaries appointed labour overseers from each tribe to direct work crews. Such internal practical policies kept various tribesmen from losing culturally distinct identity. Further evidence of cultural persistence was the practice of various First Nations maintaining separate housing in many tribal First Nation villages built next to the missions. Finally, many former mission First Nations continued to speak their native languages and provide researchers with detailed ethnographic and linguistic data well into the 20th century.

The invading Spanish government gave 51 land grants to its colonial citizens between 1824 and 1834. These lands were actually the homelands of various tribes, which were incarcerated in nearby missions. These actions just increased the lust for more First Nations land by an expanding body of colonial ranchers. This was followed a growing chorus of demands that the missionaries surrender their monopoly on First Nations labour and to "free" the Indians (for the use of the ranchers). The power of the ranchers prevailed and between 1834 and 1836 the government revoked the power of the Franciscan priests to extract labour from the Indians and inaugurated a plan to redistribute mission lands. Greedy public officials in charge of the redistribution granted the most valuable lands to themselves and their relatives. This secularization processes, as it was called, was so restrictive that few ex-mission First Nations were eligible for the redistributed lands that were originally their homelands. More significant still, the majority of surviving mission First Nations were not native to the areas of the coastal missions having been earlier forcibly relocated for the labour camps from the interior. Most neophytes at this time had been forced to relocate from their own domains and promptly returned to them following their liberation. Many of these returned First Nations exiles were faced with difficult task of reconstructing their decimated communities in the wake of crippling population declines from disease and being worked to death. Their tribal lands had also become transformed by the introduction of vast herds of horses, cattle, sheep, goats and hogs that destroyed the native fauna and flora, the primary source of native diet.

What then developed from these new conditions was the emergence of guerrilla native bands made up of former fugitive mission native and interior tribesmen from villages devastated by official and unofficial Mexican paramilitary attacks and slave hunting raids. With the hunt for slaves, it is little wonder that they could readily accept escaped black slaves from the south and eastern plantations when the contacts occurred. In addition, the blacks also a people that could live easily from nature, could readily adapt to First Nations ways with little additional training. These interbred and gave birth to the Metis and other dual parentage minorities. Eventually a significant number of these interior groups joined together to form new confederacy of tribes similar in scope to the north eastern Iroquois Confederacy of nations. These innovative and resilient First Nation tribes quickly converted the anti-mission activities of their members into systematic efforts to re-assert their sovereignty. This was effected by widespread and highly organized campaigns against Mexican ranchers and government authority in general regardless of whether Spanish or English speaking.

But this reprieve was to be temporary as a new scourge in the form of malaria was to take hold. Before this, the sudden acquisition of horses from the Spanish missions was to drive the lust for more and ranches were invaded for their horses and live stock. Some of the desire for horses was driven by the American and Canadian fur trappers and traders that acquired them from the First Nations. But these same fur hunters and traders were the ones that introduced malaria that decimated many communities to a handful of individuals. In this tragedy more than 20,000 Central Valley Miwok, Yokuts, Wintun, and Maidu First Nations perished. Further, a new outbreak of small pox devastated Coast Miwok, Pomo, Wappo, and Wintun tribes. Approximately 2,000 native people died during this 1837 epidemic originating from Fort Ross. By 1840 these and other deadly diseases had so thoroughly saturated the First Nations of Mexican California that diseases became endemic. The First Nations were powerless to deal with this deadly tide of multiple diseases.

Spanish Mexican forced labour, violence at the hands of the militia and paramilitary and slave hunting parties account for a significant amount of the population decline suffered by California First Nations. On the eve of the American takeover the First Nations population of approximately 310,000 people had been more than halved to about 150,000. This precipitous decline had occurred in just 77 years. The implications for survivors is largely a mute tale of suffering and grieving over the loss of a stunning number of children, parents and elders. What came next was worse still under the Indian Removal Act and the eventual “Trail of Tears” that took so many lives, that many First Nations were brought to the brink of extinction.