The Curse of King Tut

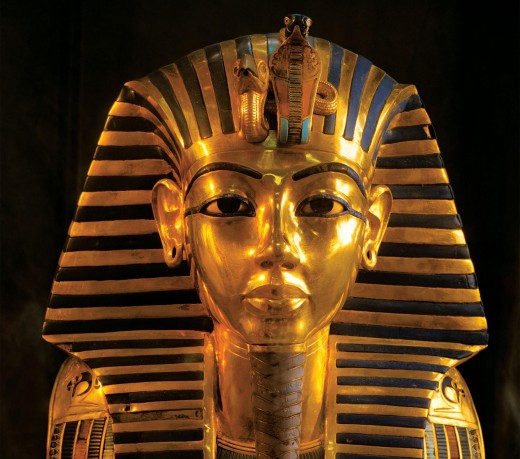

On November 4, 1922, the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamon was discovered by English archaeologist Howard Carter. The official opening of the tomb took place a few weeks later and was attended by local politicians and dignitaries. News of the fabulous objects inside the tomb spread quickly around the world and when the burial chamber was opened, almost four months later, dignitaries from all over the world were present. Euphoria quickly turned to apprehension and even panic, however, as people who visited the site began to die under mysterious circumstances, and it was not long before the newspapers had come up with the idea of a "curse" plaguing those who had desecrated the young pharaoh's tomb.

The young pharaoh's tomb. The film runs through the usual litany of deaths and other strange occurrences reported by enterprising (and sometimes highly imaginative) journalists in the 1920s, and although the tone is a bit too sensational, the program sticks fairly close to the facts. There are wonderful stills of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, his patron, as well as both moving and still shots of the tomb's official opening in 1922. A most engaging sequence features Lord Carnarvon's son reminiscing in 1931 about the opening of the tomb and his father's sudden death less than six months later. He is a re-markable character, almost a caricature of the dotty English aristocrat, but his memory seems in-tact and he provides terrific color for the film.

Throughout the first phase of tape artifacts from King Tut's tomb serve as a backdrop for much of the discussion. Then the scene shifts to Poland where in 1973 a team of 14 scientists opened the graves of King Casimir of Crakowand his wife, Queen Elizabeth, who had died in the years 1485 and 1505, respectively. Within a year four of the scientists were dead of lung diseases. Later, eight more died.

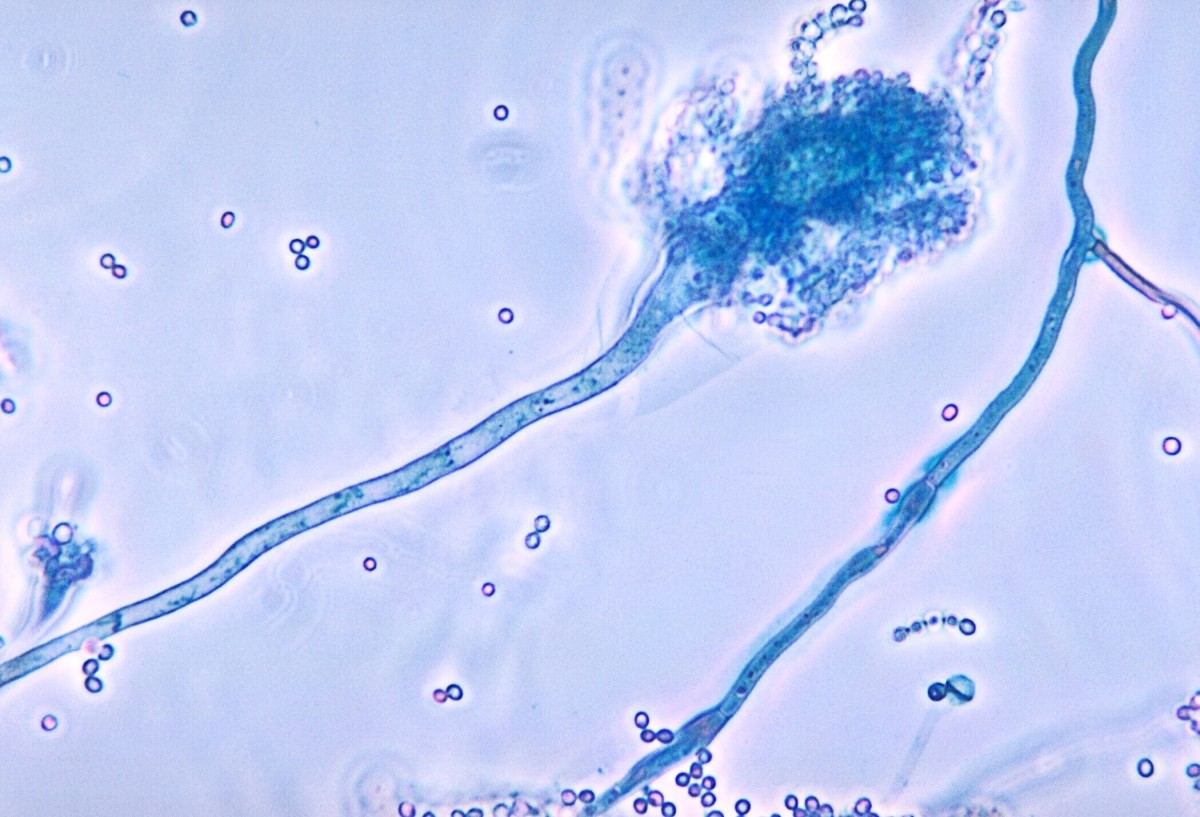

The film makes a case for the presence in ancient graves of a deadly fungus, probably a member of the genus Aspergillus. It is hypothesized that the unexplained deaths of those who visited Tut's tomb as well as of the 12 Polish scientists can be attributed to respiratory infections resulting from exposure to toxic Aspergillus fungi, and that the so-called "Coptic illness," a respiratory ailment common among those who study Coptic textiles from Egypt, is probably a non-lethal variant. One of the Polish scientists who survived the encounter with the remains of King Casimir and Queen Elizabeth supports this argument, and claims to have isolated and cultured in his laboratory the deadly fungus recov-ered from the grave. His testimony in the film is quite convincing.

Unfortunately, this production is seriously compromised by subsequent sequences. First is an excursion into speculation about whether the poisoning of King Tut's tomb deliberate—some fiendish plot concocted by the pharaoh's personal physician to insure the punishment of anyone who desecrated or robbed the tomb. Such an idea, though worthy of brief consideration, is so far-fetched as to be almost completely untenable. But it makes for a good story. Far more egregious, and totally gratuitous, is the final eight or ten minutes of the tape which have nothing whatsoever to do with Tutankhamon or the famous curse. Here we have a rambling and totally unquestioning examination of "pyramid power," the idea that the pyramid form causes a "concentration of energy" that can sharpen razor blades, keep meat fresh, and perform many other improbable tasks. Presented as fact, this totally fanciful bit stands in stark contrast to the reasoned scientific approach used to examine the "curse" of King Tut.