The Dinwoody Formation: What Is It? And How Did It Happen?

Abstract

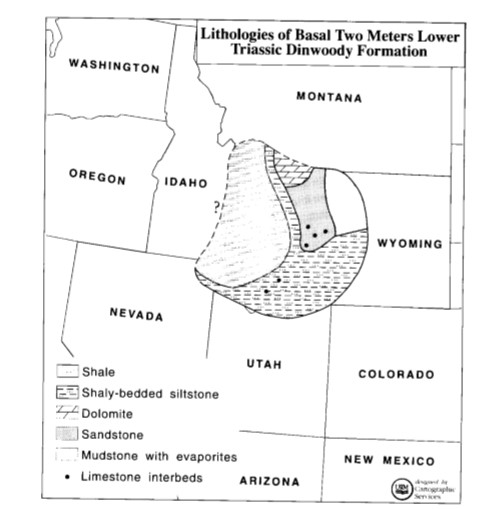

The Dinwoody Formation is a silty shale formation with increasing layers of bio clastic limestone that stretches across Eastern Idaho, Western Montana, Norther Utah, and Northeastern Wyoming. The formation was made along the foreland basin Antler Orogeny in the Cordilleran Miogeocline. It was created in the Dinwoody Sea. The sea was developed from a series of early Triassic Griesbachian Age transgression regression cycles. The transgression regression cycle washed in sediments and allowed them to settle in an inner shelf, middle shelf, or outer shelf hypersaline environment. The sedimentology of the area is incredibly variable from area to area consisting of silty dolostone, silty shale, sandstone, and gypsum, though it did carry a general pattern of siltstone of becoming more dolomitic for many areas of the basin. The proportion of what is dominant in the stratigraphic column of the Dinwoody depends on the shallowness of the water at the place of observation in the basin and how much organic calcite is available. During this time, the Dinwoody also left a biostratic timeline that recounts the rebound of life after the post Permian extinction. The abundant fossils helped to confirm environments that the both the sedimentary structures and stratigraphy suggests a about the depositional environment.

What Is The Dinwoody?

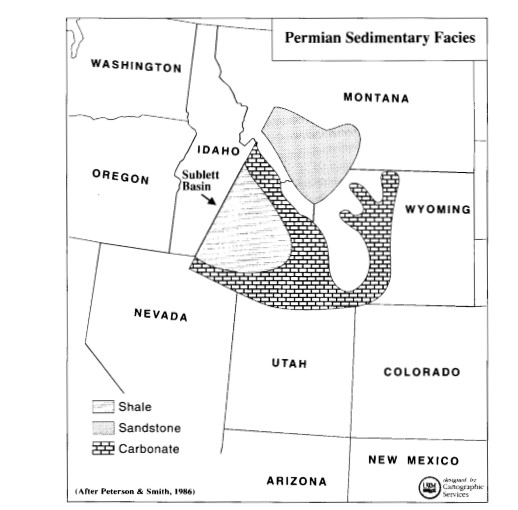

The Dinwoody is a post Permian extinction early Triassic formation that lies above the Shedhorn Formation and below the Woodside Formation. The Dinwoody, in the simplest definition, can be considered as a siltstone that becomes more progressively interlayered with fossiliferous calcareous dolostone with decreasing depth. The limestone becomes much more abundant with time. But it is not entirely restricted to the definition. The Dinwoody is a big formation that covers parts of Idaho, Southwestern Montana, Western Wyoming and the Northern part of Utah (Dennis 2006, Kimmel 1954, Paull 1986). In the stratigraphic view of things, the Dinwoody is the layer above the Shedhorn sandstone formation, (Kummel 1954, Paull 1986), but because it stretches across such a large area with a complicated plate tectonic and depositional history, the Dinwoody interfingers with both the Shadhorn Formation and parts of the Phosphoria Formation which is commonly below the Shedhorn (Paull 1986). It is variable depending on the area because of the very deep basin like structure in this portion of the United States. The thickest part of the formation is 750 meters located in Southeastern Idaho, and it gradually pinches out the boundaries of the formation (Paull 1986).

Back History Prior To The Triassic

Prior to the early Triassic, which is when the Dinwoody was deposited, there were a couple things that set the gears in motion to allow the Dinwoody to form later on.

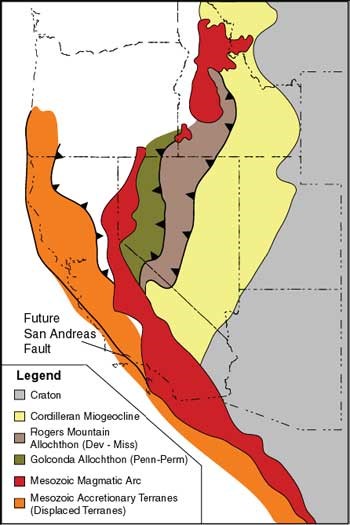

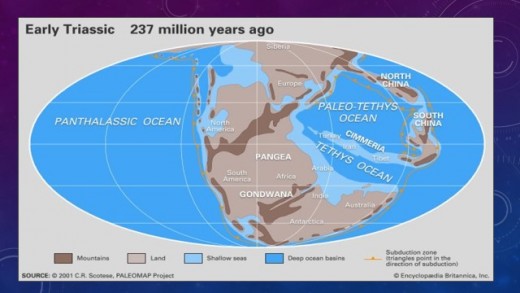

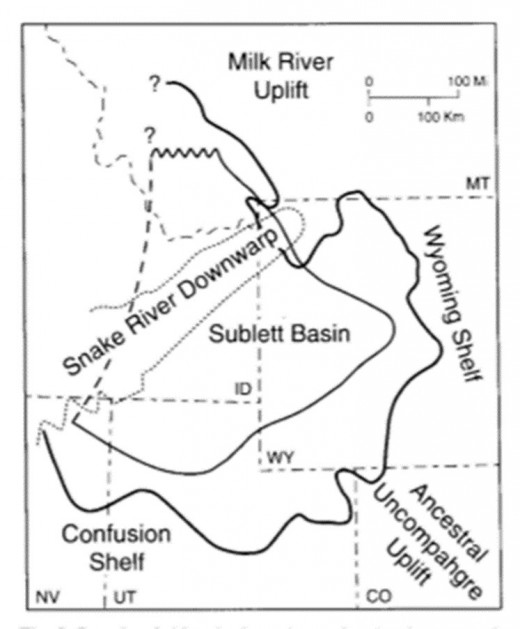

The first and earliest thing that happened was the creation of the basin that the Dinwoody would settle in many years later. The area is actually a foreland basin that formed due to Antler orogeny from a thrust fault mountain building event from when the west coast crashed onto the continent. This event that began back in the last Devonian and stretched into the Permian. This is where the Western States Cordilleran Mountain Belt was built. The Roberts Mountain Allochton thrust on the eastern edge of mountain belt form the western boundary of the basin (Suppe 1986). The down dip of the foreland created a subsiding basin. The subsidence of the thinning lithosphere of the foreland basin continued into the early Triassic. (Paull 1986).

The second thing has to do with the world climate before the late Permian extinction. In this time the conditions was extremely arid and the world was hotter than it ever been. The sea levels were extremely low, as in well below the sea level by 40 meters below the world’s lowest basin. So in these extreme conditions, great wind erosion took place (Paull 1986). This led to tons of loose fine sediment covering all dry land which will be very important for the Dinwoody deposition and is mostly the cause for the disconformity between the Dinwoody and Sheldon Sandstone. The washing in of this sediment from later transgressions have created a disconformity appearing as a 1 to 6 million year gap in the geologic rock recorded depending on what part of the Dinwoody is being investigated (Paull 1986). The disconformity boundary features many fluvial channels from the in wash and weathering. Many areas at the disconformity features a pre Triassic rocks and sediments reworked into conglomerates (Paull 1986).

Figure 1

This image shows he major thrust faults that resulted from the great Antler Orogeny. The pale yellow represents the Cordilleran Miogeocline wedge that is the foreland basin of the orogeny. The map also shows the defined the western boundary to the basin and future Dinwoody Sea at the nearest thrust fault. Subsidence continued in the basin until the early Triassic (Suppe 1985).

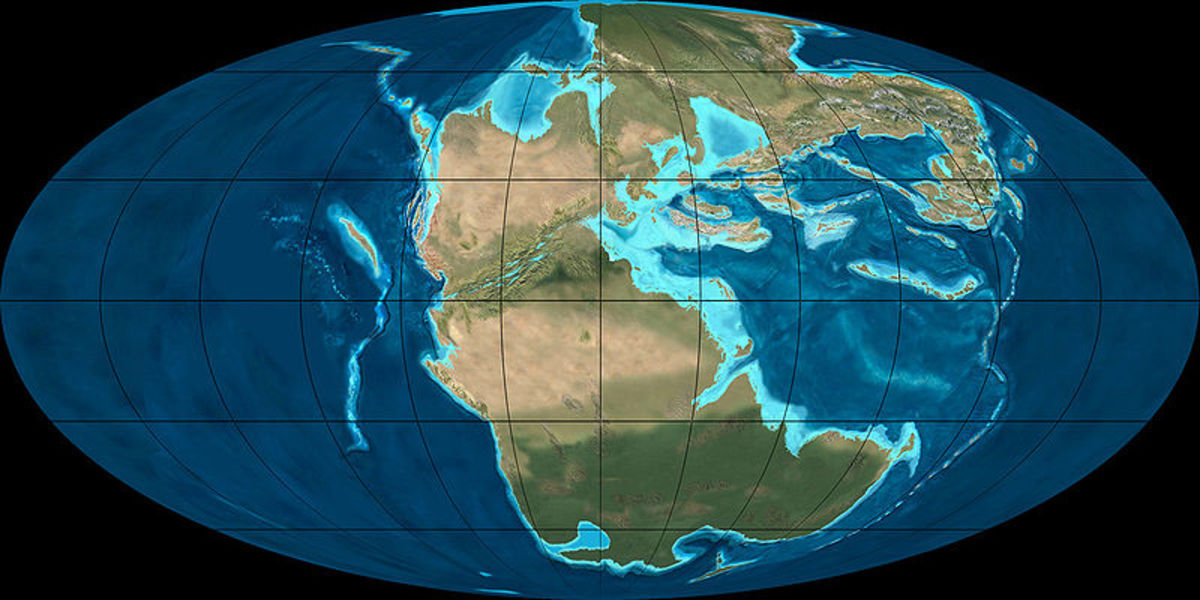

The Early Triassic and Griesbachian Age

The Dinwoody Formation was formed in the early Triassic during the Griesbachian Age. During this time, after the end Permian mass extinction, the climate of the earth was shifting. The earth was extremely arid but still much cooler compared to the late Permian. Because of this, sea levels rose. At the time, the continents held the formation of Pangea and the area of interest was right at the equator with a high evaporation rate and hypersaline water (Paull 1986). During this time there were three transgression that washed down through Alaska and Canada to the bowl like current Snake River area in Idaho and Montana area creating the Dinwoody Sea. The first transgression was very rapid covering 270,000 square kilometers. The second was just as rapid. This time covering more area, up to 310,000 square kilometers. The third was gentler and covered a smaller area of the basin. During these transgressive, in washes brought fin silts, clays, and sands into this area for deposition (Paull 1986

Paleoecology and Depositional Environment

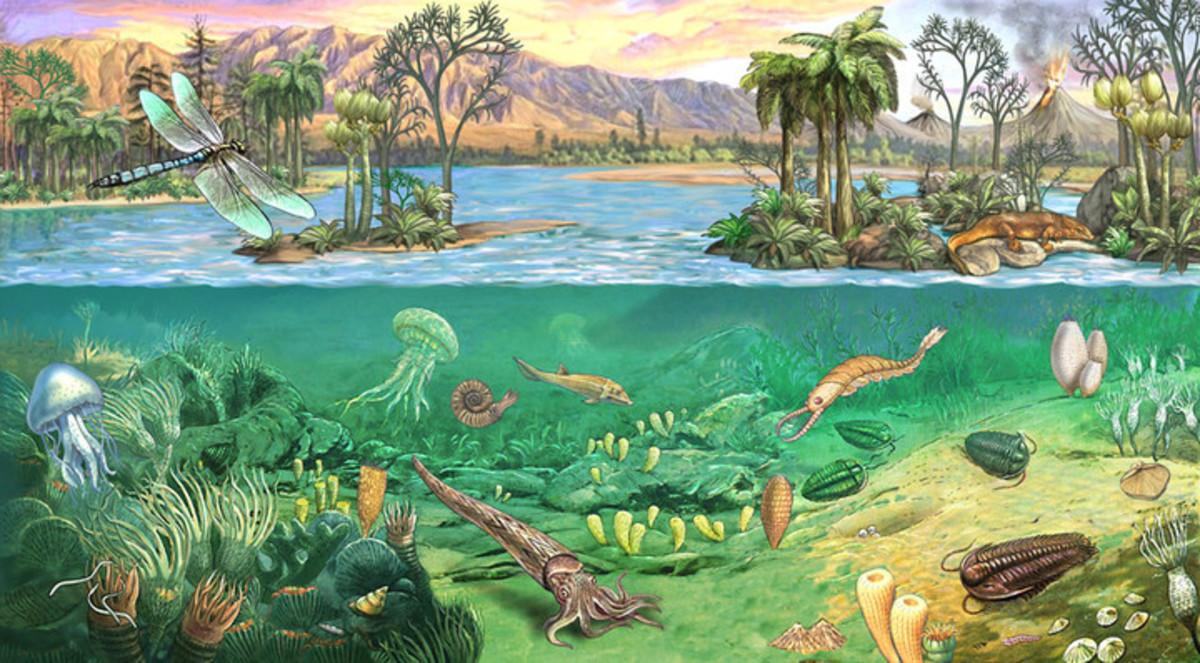

The Dinwoody Formation is intriguing formation. It very much acts like a timeline for the rebounding life after the end Permian extinction. And oddly enough, in turn this time line gives an insight to the conditions that the Dinwoody was deposited in.

Post Permian ichnofacies had limited life and low biodiversity that grew over the earlier Triassic Griesbachian age. And it can be divided into three subcategories through the timeline if this age. The first and earliest division had been called the Basal Zone (Bucher 2013, Johnson 1993). This is the time right after the extinction composed of mostly siltstone and incredibly low biodiversity. What is seen in the basal layer near the disconformity are conodonts and ammonites that were washed in from the first transgressions (Paull 1993). Ammonites disappear right after this one spot but conodonts still appear through the basal layer (Paull 1994). Conodonts only show up in the deepest parts of the basin near the western edge of the basin. Beyond that at most, the organisms that existed during this time were tiny skeletal creatures that turn out to be allochems that created small amount of calcite. The second and last categories in the timeline are called the Lingula Zone and Claraia Zone, respectively. The Lingula zone is where life begins to rebound in a strong fashion featuring fossils from the Lingula family. At the end was the Claraia Zone. This is when the biodiversity is extremely high. The most abundant taxa in the age are from the Claraia family. The region is very bioclasticly oversaturated with fossils.

The abundant fossils are inarticulate bivalve creatures lived incredibly high energy marine all near shore environments. The continuity of these creatures also means that there were few fluctuations in the salinity of the water and that it remained as hypersaline water throughout the history of Dinwoody Sea. The high energy sea water indicated here also falls in line the sub tidal sedimentary features (Bucher 2013).

Sedimentation and Stratigraphy of the Dinwoody

Earlier the Dinwoody was given an over simplified definition, is a silty shale composition with increasing calcite with time. But the definition doesn’t hold true for the entire formation. The Dinwoody overall has a very uneven structure as it a lopsided basin that through three transgression regression cycles of remarkably different sizes. But there are a few things that hold true generally throughout the whole formation. These are the noticeable units seen in the Dinwoody.

Unit # 1: Siltstone and Shale

- First stratigraphy early on was composed of settling silt and sand from the wash in from the transgressions. This settling of the fine grained material left, silt stone interbedded with shale and dolomite(Bucher 2013, Bottjer 2004, Paull 1986). It often is a green grey that weathers to yellow tan to a yellow brown.

Unit # 2: Sandstone Layering

- The heavier sediments that were washed in such as sand was the first to settled after transgression layers here and there. They often exist as reworked Shedhorn sandstone that was washed in. Sandstone has been found with channeling and ripple marks from high energy regime possibly from the in wash. (Paull 1986).

- Sandstone also built up on the shore line and very shallow eastern edges of the sea where a sandy shoreline did build up to the sea. Ripple marks are often found in the sandstone from the sea shore environment.

Unit #3: Silty Dolomite

- Over time though calcite built up into fossiliferous and organic limestone over time. The later the date, the thicker the layers where in many cases it would become dolomite. This is because the rebound of the life after the end Permian extinction. At the life returned more calcite organic became more abundant, there were more allochems to build up limestone that would later become dolostone. There was also rapid evaporation that promoted limestones formation. It is commonly brown in color. Like the sandstone, some of limestone can be found with ripple marks. (Bucher 2013).

Unit #4: Gypsum

- Another note, is that there are areas in the Dinwoody basis stratigraphy where there are couple meters of gypsum present. This most likely due to the rapid evaporation of the Dinwoody Sea. At low water levels (50% of regular water content) before regression, gypsum precipitated creating these layers. This also appears more often the eastern side of the basin where the water is more shallow water environment (Bucher 2013)

Variability is concentrations of what proportions of rock depend on where and how exactly the stratigraphic column in single locations will play out can be all related to one simple factor, the depth. The depths of the part of basin being observed plays a huge role (Paull 1986). This is because the Dinwoody featured inner shelf, middle shelf, and out shelf environment.

Conclusion

After all the research, it was discovered that the Dinwoody Formation is not as simple of a formation as one originally would think. There are many factors leading up to even having the possibility of this formation happening. An orogeny, an extremely erosional dry spell, and rising sea levels set the gears in motion to create the Dinwoody Sea which lead incredibly variable stratigraphy. In the stratigraphy it was learned it was not just increasingly dolostone layering in a silty shale. In fact it was much more complicated than that. There is indeed a general trend of more limestone abundance as life rebounds. The sea fluctuations, depth and location within the Dinwoody led to these variations. Outer shelf environments tend to have much more shale and silt in its stratigraphy more than the other shelves. The middle shelf is more dominated with interlayers of carbonate rock. The inner shelf is more dominated by sandy interlayers.

Referrences

Beatty, Tyler W., Henderson, Charles M., Zonneveld, J-P, 2008 Anomalously Diverse Early Triassic Ichnofossil Assemblages In Northwest Pangea : A Case For Shallow Marine Habitable Zone : Department of Geosciences, University of Calgary, Canada, Alberta.

Bottjer, David J., Boyer, Diana L., Droser, Mary L., 2004, Ecological Signature of Lower Triassic Shell Beds of the Western United States : Palaios, v. 19, p. 372 -380.

Bucher, Hugo, Hautmann,Michael, Hoffman, Richard, 2013, A New Paleoecological Look At The Dinwoody Formation (Lower Triassic Western USA): Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Controls On Ecosystem Recovery After The End Permian Mass Extinction : Journal of Paleontology, vol. 87(5), p. 854-880.

Condit., D. Dale, 1918, Relations of Late Paleozoic And Early Mesozoic Formations of Southwestern Montana And Adjacent Parts of Wyoming, Shorter Contributions to General Geology 1918.

Dennis, Bob, 2006, An Integrated Petroleum Evaluation of North Eastern Nevada, Western Cordilla.

Johnson, Edward A.,1993, Depositional History of Triassic Rocks in the Area of the Powder River Basin, Northeastern Wyoming and Southeastern Montana: U.S. Geologic Survey, Bulletin 1917.

Kustatscher, Evelyn, Preto, Nereo, Wignall, Paul B., 2010, Triassic Climates - State of the Art and Perspectives : Palaeogreography, Palaoclimatology, Palaeoecology, vol. 290, p. 1-10.

Kummel, Bernhard, 1954, Triassic Stratigraphy of Southern Idaho and Adjacent Areas : United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey, Geological Survey Professional Paper 254-H.

Paull, Rachell K., Paull, Richard A., 1986, Depositional History Of Lower Triassic Dinwoody Formation, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana: Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences at The University of Wisconsin.

Paull, Rachel K., Paull Richard A., 1993, Interpretation of Early Triassic Nonmarine - Marine Relations, Utah, USA : Geosciences Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee..

Paull, Rachel K., Paull Richard A., 1994, Shallow Marine Sedimentary Facies in the Earliest Triassic (Griesbachian) Cordilleran Miogeocline, U.S.A., Sedimentary Geology, vol. 93, 181 - 191.

Scotese, C.P., 2001, Atlas of Earth History, PALEOMAP Project, Arlington, Texas, 52 pp.

Suppe, John, 1984, Principles of Structural Geology Chapter 13: North Americas Cordillera, Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences, Princeton University, p. 453 to 505.

Thomas, Dr. Robert C., 2013, The Geologic History of Dillion Montana Area : Environmental Sciences Department at the University of Montana Western.