- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

The First Indy 500

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the infancy of the automobile industry and, in this infancy, the automobile was evolving from a ‘horseless carriage’ into a car. However, as the automobile industry was in its infancy, so was America’s highway system and this led to the inability of manufacturer’s to test potential top speeds of new cars due to the poor state of the public roadways. Carl Fisher, an Indiana car dealer, realized this dilemma and in 1906 proposed building a private auto testing facility. The result was the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He built the Speedway, a two and a half mile oval with a brick surface, on 328 acres of farmland five miles outside of downtown Indianapolis.

While the track would be used for testing, Fisher and his partners wanted to bring in races to support the track. The idea was that occasional races between the new models would allow them to showcase their full power and entice spectators to check out the new vehicles themselves. The idea evolved into a decision to focus on one long race per year in order to attract more publicity. They would make it more than a car race; it would be a spectacle.

Several different length races were considered including 24 hours, but Fisher decided that the right time for spectators to spend at the track was around seven hours and, at the speeds of the day, that worked out to about 500 miles. Entry blanks were sent out to see what type of response they would get. Forty-six came back and the Indy 500 was born. With the wheels set in motion the inaugural race was set for May 30, 1911.

The Field

Typical entry fees for car races at the time were one dollar per mile so it cost a team five hundred dollars to put forth an entry. This limited the field to only serious efforts. Of the 46 who responded to the invitations, two were no-shows, two were deemed too slow to qualify (to qualify you had to maintain 75 mph along the quarter-mile straightaway), and two were too damaged to compete following practice mishaps.

The starting grid was filled out by the postmark date on a team’s entry form. There were nine rows of cars. The first row had the pace car in the pole position with four other cars, rows two thru eight had five cars each, and the ninth row had one car. This was the first time a rolling start was used with a pace car. The idea was that once the race was underway the cars would be moving so fast going by the grandstands the people would not be able to get a good look at them. The pace car would provide a parade lap and at the same time allow the cars to get up to speed in an organized manner.

How the cars actually got to Indianapolis is a bit different than how they do it today. A team from Massachusetts had two cars entered in the race. They loaded them with everything they would hold and drove them across country. The trip took five days.

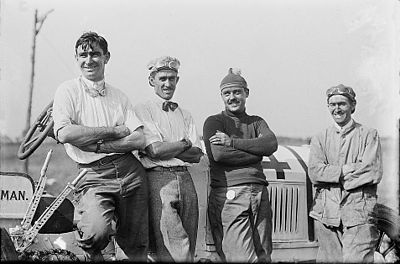

The race cars were also two-seaters, all but the eventual winner actually. The second seat was occupied by a riding mechanic, whose job while racing was to look out for other cars, especially when passing. The driver who raced alone, Ray Harroun, employed the use of the first-ever-recorded cowl mounted rearview mirror. After the race Harroun commented that the mirror was pretty much useless in that it vibrated so much he really couldn’t see anything in it.

Some of the teams also employed relief drivers. They would take over the driving during the course of the race, usually towards the middle and give the driver a break. One relief driver, Cyrus Patshke, drove for both of his team’s cars, including the eventual winner.

The Race

The race was rather uneventful until the 13th lap when a multi-car pile up in front of the grandstand that included the death of one of the riding mechanics created chaos. During all of the confusion the scoring broke down when the scorers, many of them Fisher’s friends, scurried out of the way when the cars crashed near them. For several laps no one was scoring the action but it didn’t become an issue until after the race when the runner-up, Ralph Mulford, argued he was the rightful winner. His claim was dismissed even though the validity of that claim is still arguable today.

Fourteen cars failed to finish the race and Sam Dickson was the lone fatality. Ray Harroun took the checkered flag with an average speed of 74.602 mph and a time of 6:42:08. He started in 28th place and no driver has ever won from farther back. For his efforts he earned $14,250. Today his car, the ‘Marmon Wasp’ is on display in the Speedway museum.

Today

The Indy 500 is still 200 laps, that’s about the only thing that has stayed the same. Except for a small strip of bricks the course is now all banked macadam and the start is eleven rows of three abreast. The pace car is still employed but is positioned in front of the pack. The pace car will do laps faster than Ray Harroun. The winning time will be much less than half the time taken in the first race, unless there are a lot of yellow flags it should be just under three hours. The cost of the cars and the prize money are so disparate it isn’t really even possible to compare them. I can guarantee you no one drove the car they intend to race to Indianapolis.