- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Religions of the Founding Fathers

Check out my (Freeway Flyer/Paul Swendson) American History book:

Does the United States Have a Particular Religious Heritage?

When it comes to the religious beliefs of the Founding Fathers, there are two generic, competing narratives. On one side of the spectrum, there are people who believe that the Founders were basically mainstream Christians, and because the Founders viewed life through a Christian lens, they inevitably laid down the basic principles of this nation on a Christian foundation. So when they talked about the separation of church and state, they did not mean that all references to Christianity should disappear from public life. Since Christianity was so central to the fabric of the United States, utterly eliminating Christian references from anything connected to the government would not only be impossible. It would actually be un-American.

On the other side, you have a narrative in which the Founders were closer to being a bunch of secular humanists. Sure, many of them professed a belief in God. But when they were not merely catering to their often religious audiences, the God that they talked about was more of a deistic conception in which the creator established the universe with certain natural laws in place and then let it unfold on its own. He was not the omnipotent, Judeo-Christian God intervening in human affairs and performing miraculous feats that contradicted the laws of nature. So instead of turning to divine revelation for wisdom, the Founders were students of the Enlightenment who turned to science and reason as true sources of knowledge. And because they were well aware of the impact of religious persecution, bigotry, and superstition, they understood the importance of establishing a firm separation between church and state and stating very clearly that freedom of religion would be protected in this new republic.

So which narrative is correct? Were the Founders influenced by Christianity or the Enlightenment? When modern controversies arise involving the separation of church and state, would they come down on the side of evangelical Christians or the ACLU? As always, any simplistic answers to controversial historical questions are inadequate. Reality is always more complicated and interesting than generic historical narratives. The Founders were a collection of individuals, and just as they disagreed with one another about many political issues, they also had a variety of religious beliefs. And to make things even more complicated, the religious beliefs of these individuals often changed over the course of their lives. So if your goal is to promote either one narrative or the other, you can find plenty of quotes that will make these prominent men sound like Christians and others that will paint them as a bunch of religious skeptics/Unitarians. To demonstrate what I mean, I will give a brief summary of the religious beliefs of some of the biggest names:

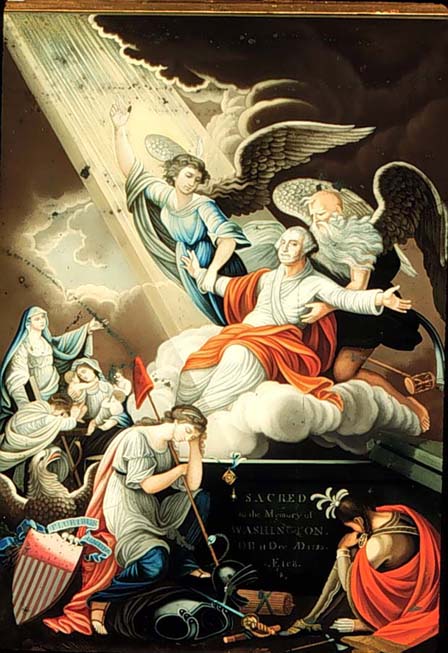

George Washington

You could make the case that George Washington, the “father of our country,” is the biggest name in American History. It is no surprise, therefore, that there has been much debate regarding the religious beliefs of this American legend. This controversy, however, demonstrates an important point that is also true with most of the men I will discuss here: he was not particularly forthcoming about his personal, religious beliefs. Washington was essentially a practical, action-oriented man, so he focused on practical spiritual issues, not complex theological abstractions.

In his personal letters and sometimes in speeches, Washington expressed a belief in God’s providence, a possible afterlife, and divine justice. He also attended Anglican Church services pretty regularly – where he served as a vestryman – and displayed in his writings a pretty advanced knowledge of the Bible. But according to the accounts of many contemporaries, Washington never took communion, and to this day, no one is quite sure why. Does this indicate that he did not accept all of the tenets of Christianity? Does it indicate that this man, who was a harsh judge of his own character, did not feel worthy to take communion? We don’t know, and I find it fascinating (and even enlightening) that he never told anyone why.

Washington, however, clearly stated on many occasions his annoyance with any form of religious bigotry. He was even known to attend the services of various religious denominations from time to time, including much disdained groups such as Catholics and Quakers.

Thomas Jefferson

If you asked Jefferson whether or not he was a Christian, he would likely, particularly toward the end of his life, say that he was. But if you pressed further, and if he began to explain his beliefs in more detail, you would quickly realize that he was not a Christian in a Biblical sense. Over the course of his life, Jefferson developed a deep appreciation for the moral teachings of Jesus, concluding eventually that Jesus was the greatest moral teacher of all time. But Jefferson believed that the simple teachings of Jesus had been corrupted by some of his so-called followers, particularly the ultimate villain: the apostle Paul. According to Jefferson, Paul had tacked on various Platonic, complex, theological abstractions that had nothing to do with what Jesus had said. And down to Jefferson’s day, Christian religious leaders, who Jefferson also generally depicted as villains, had been exploiting these complex ideas, forcing average people to come to “priests” for “explanations.” Ultimately, in an attempt to right these wrongs, Jefferson essentially rewrote the New Testament, taking out miraculous events and the various letters of the apostles but leaving the moral teachings of Jesus intact.

But while Jefferson was hostile toward orthodox Christianity, he was hardly anti-spiritual. In fact, the older he became, the more he appeared to develop what he called an intimate relationship with a loving God. So if you want Jefferson to be a deist, it is best to look at his early writings. If you prefer Jefferson the quasi-Christian, quote the letters from Jefferson the old man.

There is one religious belief of Jefferson, however, that is unquestionable. Jefferson, throughout his entire life, was a strong supporter of freedom of religion, arguing passionately for a wall of separation between church and state. One of his proudest achievements, in fact, was his contribution toward the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which ended government support for the Anglican Church in his home state. And in line with this belief, he rarely expressed his personal religious views in any public forum, even refusing to proclaim any national days of prayer and thanksgiving. This may have played some part in false claims by political opponents, particularly during the 1800 presidential election, that Jefferson was an atheist.

James Madison

While Washington is generally acknowledged as the “Father of our Country,” Madison is often depicted quite accurately as the “Father of the Constitution.” More than any other individual, Madison shaped the basic structure of what became our system of government. So if you want to make the case that the Constitution is based on Christian principles, then the religious beliefs of Madison would be a good place to start.

The only problem is that Madison was not particularly forthcoming about his religious beliefs. This was not, however, from a lack of interest in religion. Madison, in fact, displayed as intense an interest in religion as he did in politics, and he approached the subjects in the same way. Just as he studied hundreds of governments throughout history in preparing for the Constitutional Convention, he studied philosophers and theologians writing from many points of view. And as he grew older, this person who as a young man was apparently a conventional Christian seems to have evolved into more of a deist. His basic ethical system, however, stayed rooted in Christian principles.

But like Jefferson, the one undeniable principle that Madison vigorously upheld was the separation of church and state. He also, like Jefferson, played a significant role in passing the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. If anything, however, he wanted the wall between church and state to be even stronger than Jefferson, even opposing the idea of assigning chaplains to each house of Congress. In Madison’s view, any connection between church and state was bad for both government and religion. And I’m sure that he would find it remarkable that modern, evangelical Christians, who in so many ways oppose excessive government, would want the federal government to promote religion in any way.

John Adams

As a member of a Unitarian Universalist Congregation, I, along with my fellow travelers, can claim John Adams as the famous Founder closest to our line of thinking. He believed that God revealed Himself through reason, not through miracles or inerrant scriptures. He felt that the Bible contained valuable insights, but he also believed that people should study the scriptures of other religious traditions as well. For him, the notion that a loving God would condemn people to an eternal hell was nonsense, and so was the idea that God came down to earth in human form to die on a cross.

Outside of a general belief in a loving God, divine providence, and an afterlife, the one Christian belief that he seemed to most absorb was the concept of original sin. As a son of Massachusetts, it makes sense that this idea so emphasized by Calvinists would sink in to the psyche of Adams. In himself and in others, he tended to see the dark side and the internal contradictions of human nature. And for this reason, he thought that religion was essential; because without religion, human beings would inevitably drift into sin. So he may not have been as optimistic as your average Unitarian, but his belief that behavior mattered more than theology is probably the central tenet of the UU faith.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton had a pretty rough childhood. Because his parents were not technically married, Hamilton was often labeled a “bastard child” throughout his life. When he was still a child living in the West Indies, his father deserted him, his mother died, and a relative who had become his caretaker committed suicide. He was a teenager working for an import/export business when he began to display some of his amazing talents, and he drew the attention of a Presbyterian minister who eventually became his benefactor. Possibly due to this minister’s influence, Hamilton, according to people who knew him at the time, seemed to be a very devout Christian.

Hamilton’s benefactor got the money together to pay for his college education in New York, and it was there that Hamilton truly began to show his brilliance as both a student and a revolutionary organizer. With the outbreak of the American Revolution, Hamilton joined the army, eventually becoming George Washington’s right hand man through much of the war and writing much of the general’s personal correspondence. This relationship would help springboard his career as one of the most important figures in the early years of the United States, with Hamilton playing a significant role in getting the Constitution ratified and in putting the nation on a more secure financial footing as its first Secretary of the Treasury.

During those years as a major public figure, however, religion seemed to become less important to Hamilton. He rarely attended church, and like many of the Founders, he expressed concerns about the dangers of religious fanaticism. He also, however, believed that human nature was inclined toward evil, so religion was important for keeping people somewhat in line. But as often happens, personal crises eventually drove him back to his Christian faith. For all his brilliance as a public figure, Hamilton was not so good at handling his personal life. He alienated many powerful people (in both political parties), saw his firstborn son killed in a duel, constantly struggled with financial problems, and became involved in a messy situation with a married woman.

As Hamilton became increasingly frustrated by his own personal problems and by the state of his young country, he proposed a familiar-sounding solution. He announced that he would work to create a Christian Constitutional Society that would attempt to elect “fit men” to office and would perform various kinds of charity work. We do not know if this would have become an early American equivalent of the Religious Right, however, because Hamilton did not live to see it through.

Ultimately, one of those political enemies mentioned earlier, a man named Aaron Burr, challenged Hamilton to a duel. In spite of his renewed Christian faith, and the fact that his son had died in a duel just three years before, Hamilton felt compelled to take the challenge in order to defend his honor. Burr ended up shooting him, and Hamilton died about a day later. On his deathbed, Hamilton called for an Episcopal bishop to come and give him Holy Communion. At first, the bishop denied the request because the church saw dueling as a sin. Eventually, however, after Hamilton admitted his mistake and said that he had forgiven Burr, the bishop administered the sacrament.

Benjamin Franklin

There may never be another American quite like Benjamin Franklin. (Although in many ways, he was the quintessential American.) In terms of 18th century American resumes, no one can quite touch his. And when it comes to unorthodox religious beliefs, Franklin does not disappoint. Franklin seems to have even dabbled in polytheism, speculating that there might be a single supreme God, essentially detached from humanity, along with lesser Gods who run individual solar systems and sometimes intervene into the affairs of their creations.

When it came to religion, however, theology was not the key issue for Franklin. The ultimate pragmatist, he was ultimately concerned with social utility. So if an individual’s religious beliefs led to positive behavior, Franklin would argue that they were good. And since criticizing the beliefs of others was likely to cause conflict, Franklin generally refrained from saying things that could offend any particular religious denominations. He also displayed no apparent interest in converting anyone to his particular form of polytheism (or whatever it was he might believe at any particular time in his life). In the end, behavior is what mattered to him, and he felt that all people should seek to improve themselves on a daily basis, just as he had done in the course of becoming the world famous printer, writer, inventor, scientist, philanthropist, public servant, diplomat, revolutionary, and statesman named Benjamin Franklin.

It is probably best to complete this little section on Franklin with his own words, words that he wrote toward the end of this life, and words that most of the five men described here would more or less agree with:

“Here is my creed. I believe in one God, Creator of the Universe. That he governs it by his Providence. That he ought to be worshiped. That the most acceptable service we render him is doing good to his other children. That the soul of man is immortal, and will be treated with justice in another life respecting its conduct in this. These I take to be the fundamental principles of all sound religion, and I regard them as you do in whatever sect I meet with them.”

Conclusions

As I said earlier, these six men, representing our first four Presidents, first Secretary of the Treasury, and arguably the most influential American of the 18th century, did not, as a general rule, fit neatly into clear cut religious categories. This should not be surprising. Intelligent, creative, thoughtful people often defy simplistic categorizations. So why have so many Americans over the years tried to turn them into either evangelical Christians or secular humanists? And in the end, do the personal religious beliefs of these very important men in early American History make any difference? Given how little many of these men disclosed about their personal beliefs, it is clear that they did not see their theologies as politically significant. In fact, they would probably be surprised by how much attention this topic receives in the modern United States.

I tend to think, however, that many of the people who care about this subject are not interested in a scholarly, historical discussion for its own sake. Instead, whether consciously or unconsciously, they are actually arguing about our national heritage. If the Founders were Christian men building a nation on Christian foundations, then modern Christians are the ones seeking to uphold our true American values. But if the Founders were products of the Enlightenment, then our heritage is essentially non-religious, and people who place their faith in science and reason are the ones more closely aligned with American principles. The problem, of course, was that the Founders’ beliefs tended to be a mixture of Enlightenment and Christian principles, making it difficult for anyone to stake a clear claim on our religious heritage.

It is important to remember, however, that the political and legal foundations of our country are not based on the individual beliefs of a few important men. Instead, they are based on the Founders’ political actions, most notably the establishment of the Constitution. And the only thing that the Constitution clearly states about religion did not appear in the original document. Instead, we see it in the opening words of the First Amendment. Given the fact that the core principle that these six very influential men could agree upon was that freedom of religion could best be protected when the government did not “promote an establishment of religion,” it should not be surprising that the First Amendment contained the only religious principles included in the Constitution. But like all of the amendments in the Bill of Rights, it has largely been left up to us to determine exactly what the First Amendment means today, although the Founders’ views on the subject are still worth reading. Since they were closer contemporaries to a time when so many people came to this land in order to escape religious persecution, they probably had a deeper understanding than many Americans today of the dangers associated with a government closely aligned with any particular religion.