- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

The Great Awakening in America

Understanding The Declension Model

The early Puritans came to set up a New World colony in the area that would come to be known as Massachusetts. The hoped to experience a perfect colony that would be a holy commonwealth made up of true Christian believers. They hoped that their "errand into the wilderness" would result in a colony that would show Christendom in Europe how a true Christian society could operate based upon the principles of Christian love and concern for the brethren.

To ensure that this society endured, the Puritans tied political life to religious life. Only those Christians who owned the covenant and had a conversion experience could join the Congregational Church. Only those who belonged to the church could participate in political life. The Puritans made this move to ensure the purity of both church and state. However, after just one generation, the founders began to bemoan the fact that their children were concerned more with money than with making God happy.

The idea that the nation was heading in the wrong direction did not begin with the election of the latest president (whoever that might be at any given time). It actually began before the founding of America as a separate nation. The second generation in Massachusetts began to preach jeremiads that were calls to repentance for the lack of following God. These jeremiads talked of the decline (hence the terminology of declension) of Puritan society from the high state that it once held at the foundation in 1630.

Colonial Society at the Outbreak of the Great Awakening

There was a great concern that society was in decline and that God's judgment was near during the early 1700s in Massachusetts. Ministers continuously preached jeremiads that called for people to repent and turn away from their sin. Colonial ministers like Jonathan Edwards preached against the common sins of the day and feared for the spiritual deadness of their parishioners. Whether their concern was legitimate is a subject for debate among historians.

The Rise of Pietism

One of the most important spurs to the Great Awakening in the colonies was the rise of Pietism on the European continent. Mark Noll in his work on The Rise of Evangelicalism notes that this revival of religious affections emphasized a religion of the heart, rather than the cold and formal head religion of the seminary graduates.

The Pietist groups like the Moravians came into contact with important evangelical leaders like the Wesleys and George Whitefield who then came to British North America to preach. Of this group, Whitefield would be much more influential in colonial America.

Important Figures in the Great Awakening

There were many important figures in the Great Awakening. This article will focus upon just a few who were most important in the revivalism that typified the Awakening.

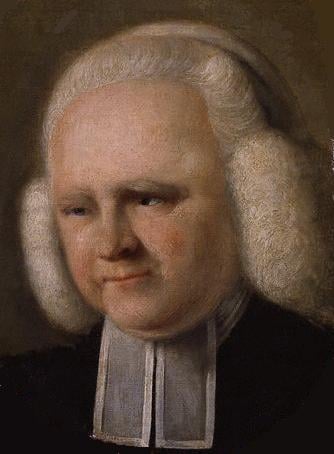

George Whitefield

Whitefield was an Anglican minister who graduated from Oxford. He earned a reputation as "the boy preacher" when preaching in London. Whitefield emphasized heartfelt sermons that demonstrated the need for what came to be known as the "New Birth"--essentially a conversion experience.

Overall, Whitefield made seven trips to the American colonies and preached in all thirteen of the colonies that would make up the United States in 1776. He made great use of his brother's knowledge of important colonials (through his wine exporting business) who could support him. The colonial press also spread word of his talents.

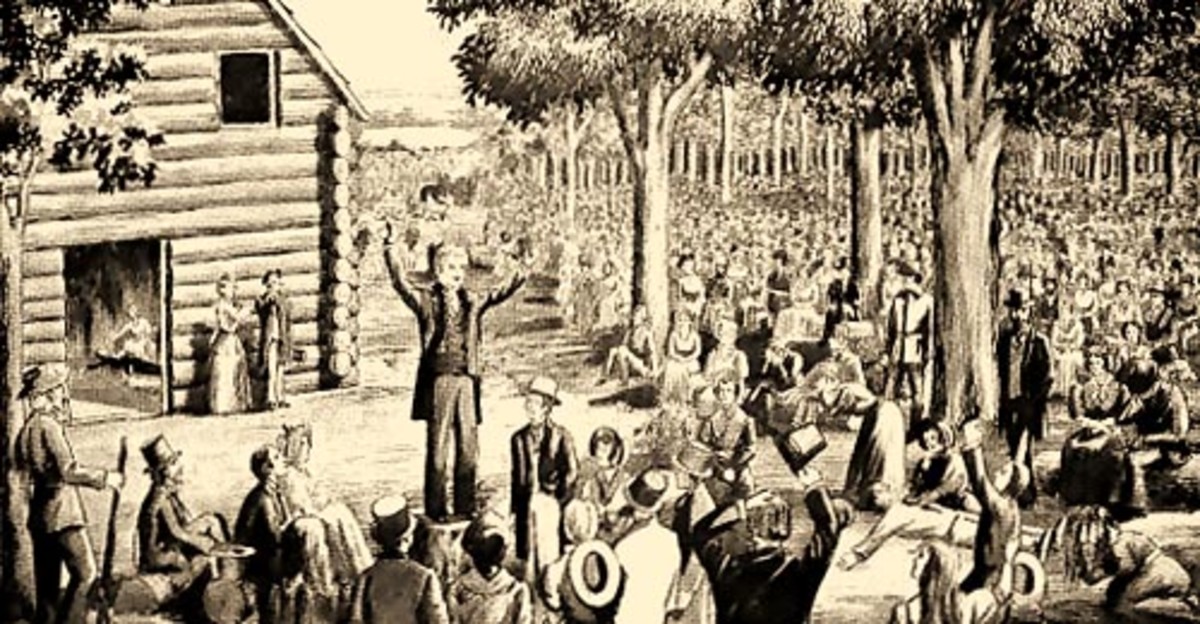

Many local ministers would oppose Whitefield and close their churches to this itinerant evangelist. This practice did not deter Whitefield, and he would just move his meetings out of doors. There are estimates that he could reach 30,000 outdoors with the sound of his voice.

The religious skeptic Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography that he went to one of Whitefield's meetings determined not to give to any of his causes. Whitefield's message led him to give all that he had in his pockets for a Georgia orphanage. Franklin also noted that another skeptic went with no money because of Whitefield's reputation of drawing people to give to his causes. The man wound up borrowing money to give.

Gilbert Tennant

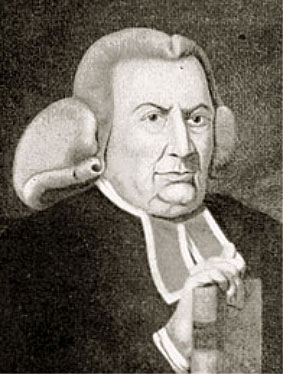

Gilbert Tennant was one of the leading colonial evangelists. He was the son of William Tennant, whose "Log College" was a precursor of sorts for what would become Princeton University. Tennant's main claim to fame was his belief that many ministers were themselves unconverted.

Gilbert Tennant's "Danger of an Unconverted Ministry" argued that there were many ministers who were themselves lost and leading their parishioners away from the gospel as a result. This claim did not win him many supporters among the establishment.

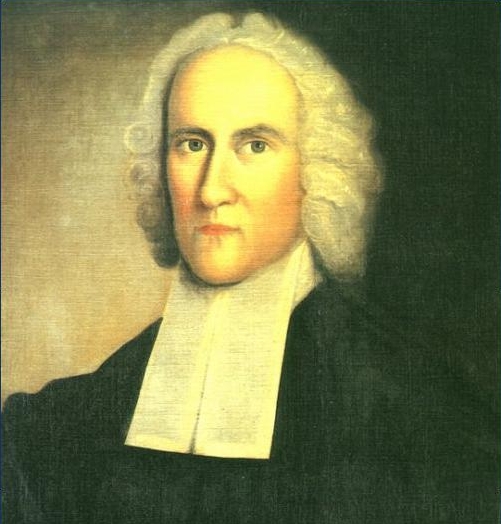

Jonathan Edwards

If Whitefield was the leading evangelist of the Great Awakening, Edwards was its leading theologian. Many historians and theologians still consider Jonathan Edwards the greatest theologian ever in American history.

Edwards was a local pastor in Northampton, Massachusetts, and experienced mass revivals in his church on a couple of occasions in the 1730s and 1740s. He would try to reform some of the leading families in town, so the congregation fired him in 1750. Edwards would spend most of the rest of his life at a backwoods Indian Mission at Stockbridge. His last few weeks were spent as president of the College of New Jersey (Princeton).

Edwards was important in the international aspect of the Great Awakening because of his many books and pamphlets that both gave the details of the revival and gave support to the movement. He gave his most famous sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God", while he visited at Enfield, Connecticut. According to the accounts of the event, many people moaned and cried out because they felt as though they would fall into Hell at any moment.

Opposition to the Great Awakening

Any major event is liable to having detractors. The Great Awakening was no different. The claim that itinerants were riling up the common folk was quite widespread. Many ministers began to oppose itinerant preachers altogether.

There was a fear on the part of opponents like Charles Chauncey that the revivalists were focusing their attention on emotions only and that there was no appeal to reason in the sermons. The "enthusiasm" of the parishioners who experienced the revival first-hand was a major reason for concern because these people would then come to oppose local ministers who they felt were unconverted.

An Audio File of Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

Important Outcomes of the Great Awakening

The Great Awakening had several important outcomes that impacted the world in which they happened and that continue to affect the direction of American Christianity today.

1. The Breakdown of Ministerial Authority

One of the aspects that many people feared about the Great Awakening was the ministry of the itinerants. These traveling preachers would draw the masses away from any ministers who opposed the enthusiasm of the revivals. This led many to question authority and also led to the decline in the amount of authority that individual ministers had over their parishioners.

2. The Splintering of Churches

Those who supported the revivals would frequently start "Separate" churches that became rivals to the established churches in areas like New England. Those who did not like their church or their minister could start moving to the church down the street. This splintering led to the current marketplace of religion that is evident in American society even today. Those who supported the revival came to be known as "New Lights" who stood against the "Old Lights" who opposed the revival.

3. The Growth of Church Membership

This is a difficult statistic to track in some areas, but there is widespread agreement that church attendance grew substantially during the Great Awakening as people experienced the New Birth and calls for increased piety.

4. The Great Awakening Was One of the First National Movements

In some ways, the Great Awakening was one of the first major events that served to tie the American colonies together. News of what was happening in Virginia would reach Massachusetts, and vice versa. Some ministers like Whitefield preached in all 13 colonies. This served to tie the colonies together to a degree that was not the case previously. Merely three decades or so after the revivals, the colonies would decide to rebel against the British. The impact of the Great Awakening on this act is a matter of debate amongst scholars.

An American Tradition of Revivalism

The Great Awakening is known by this moniker because all subsequent revivals have been compared in light of the original American revival. There is the idea that the Second Great Awakening in the early nineteenth century was more widespread, but the increased enthusiasm of this second revival made it more suspect to some.

There have been revivals on and off throughout American history since the Great Awakening. There is some question of if or when the next one will come.