The Hellenistic World: Plato's The Republic

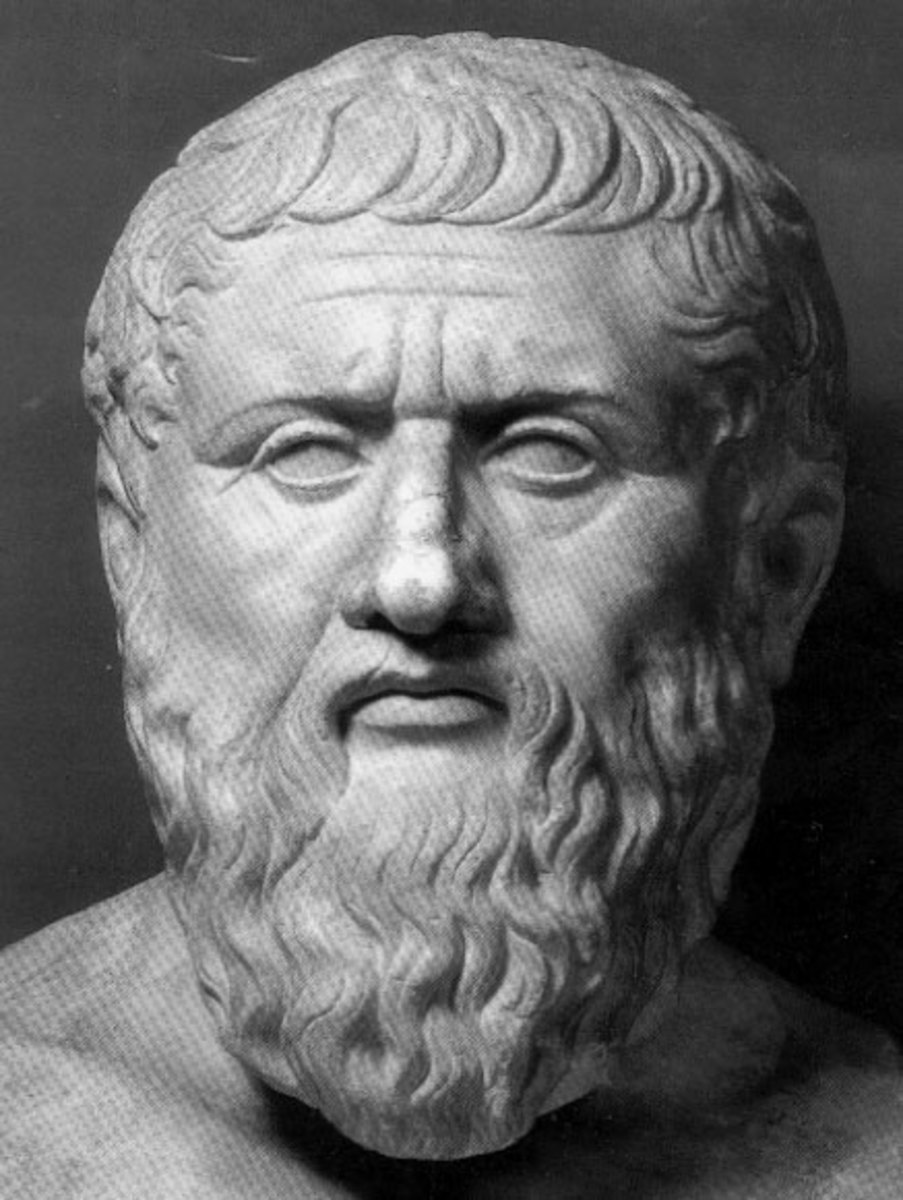

In the excerpt from The Republic, Plato gives a basic breakdown to concepts and ideas that are ahead of his time, taking the reader step by step through his reasoning, even providing a voice for the everyman, walking them through the questions and personifying the opposition. Even though his ideas were controversial at the time, and in some parts of the modern world remain so, Plato presented them in a way as being the most logical concepts.

Plato’s awareness of democracy ends up focusing on its flaws, insofar as he knows where fault lies in its lack of real foundation. One of his determinations is the lack of true equality in the system, and that is adamant that the current standards inherently sabotage the balance of power within the system. “Then we must conclude that sex cannot be the criterion in appointments to government positions” (Brophy 130). He also states “No office should be reserved for a man just because he is a man or for a woman just because she is a woman” (130). He removed what would essentially be a demographic place holder that those ruling might place in the system avoid sharing power and yet still maintain the illusion of placating the masses. There is an advocatory tone for a meritocracy for those wishing to hold these offices based on knowledge and ability.

It is interesting as to the term he uses for those holding offices. Rather that acknowledges the politics and divisions, he names them as guardians, which seems like a small throwback to an oligarchy, but aware of their positions as being chosen by the people, as the defenders of the people, removing the gender barriers that might turn voters away. “You will apply the same criteria to select women whose natures are as similar as possible to those of the men” (132). As a way to further limit the divisions amongst those that would hold government positions, Plato suggests a kind of collegiate habitation. “They will live in common houses and eat at common meals. There will be no private property. They will live together, learn together, and exercise together” (132). The danger that he might have foreseen, which was already present, was the subjugation of one gender by another, and as a man of philosophy, could conceive what might come about if the current balance was maintained for too long, and what might be the consequences when scales started tipping in the opposite direction.

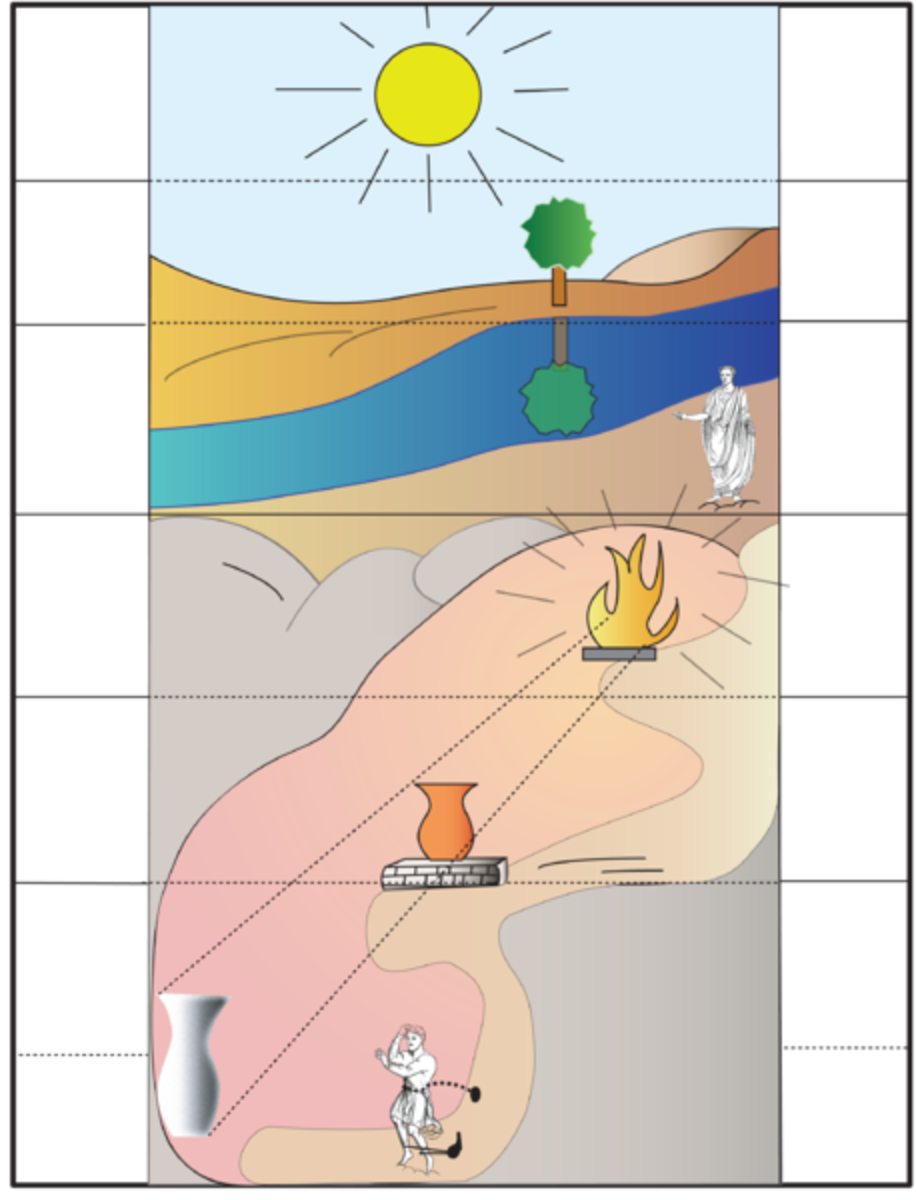

Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” from Book VII of The Republic helps us conceive of the possible paths of destruction and chaos if an ignorant population is lead by an equally ignorant rule, and the possible outcomes if enlightenment spreads too rapidly or too slowly. If we approach the movie The Matrix as an actualize representation, then our understanding of Plato’s position becomes more concrete.

Plato’s introduction to the cave is as follows: “Imagine men living in a cave with a long passageway stretching between them and the cave’s mouth, where it opens wide to the light. Imagine further that since childhood the cave dwellers have had their legs and necks shackled so as to be confined to the same spot. They are further constrained by blinders that prevent them from turning their heads; they can only seed directly in front of them” (133). He conceives the cave dwellers as being slaves to the darkness, with the darkness being a lack of education. From the movie, with the example of Neo, we can how the wakening, or enlightenment, can converge to become positive example. Neo is already in search of answers, and makes contact with those who have already stepped into the light of knowledge, having been unplugged, or unshackled from the prison he wasn’t aware that he resided in. Neo’s journey out of the Matrix echoes the single man’s journey out of the cave: “One prisoner is freed from his shackles. He is suddenly compelled to stand up, turn around, walk, and look toward the light. He suffers pain and distress from the glare of the light” (134).

For Neo, awakening was a hard but needed experience, from which he can only improve upon his current existence. For the character of Cypher, however, awakening was painful, and his enlightenment has made him bitter, resentful, and traitorous in his longing to go back to his former state in the cave. “Further, if anyone tried to release the prisoners and lead them up and they could get their hands on him and kill him, would they not kill him” (135)? Cypher’s enlightenment has not made him better, and thus makes him a Judas, leading to try to destroy those he hold responsible for what he feels he has lost, because for him, ignorance suits him better than knowledge, which to the viewer would be something akin to stupidity. “Would you think it strange if someone returning from divine contemplation to the miseries of men should appear ridiculous” (135)?

Cypher betrays Morpheus, for what he sees as a betrayal of himself. Morpheus’s betrayal of Cypher was described by Plato already: “Remain above, refusing to go down again among the prisoners to share their labors and their rewards, whatever their worth may be” (136). Morpheus’s betrayal was that he didn’t refuse to return to the cave, the Matrix, and free him from his slavery to ignorance, and it is not a betrayal that Cypher can forgive. “Must we wrong them in this way, making them live a worse life when a better I possible” (136)? Except for Cypher, the “better” is being back in the Matrix, and his awakening forgotten.

The Chosen One and the psychology for the guardians seem to run concurrent also. “The truth is that the city where those who rule are least eager to do so will be the best governed and the least plagued by dissension” (137). Neo being informed that he isn’t the Chosen One was done deliberately, with merit. He became the Chosen One not because he wanted to be, but because he didn’t. He wasn’t striving for power, prestige, or wealth. He wanted to protect his friends. “That is why we require that those in office should not be lovers of power” (137). He became the Chosen One because he chose to be.

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” said by John Acton, and this is something that Plato had already seen, and knowing that knowledge is power, hoped that enough knowledge would balance out between the two extremes, those still in the cave, and those rendered useless by their overabundance of knowledge and cannot or will not do anything actionable with it. The Matrix, as an interpretation of Plato’s allegory, represents the inherent difficulties of where and how knowledge and education are used, if there is any present. Knowledge and power often go hand in hand, but a tipping point in one direction for too long can lead to disastrous detriment, rippling out from the catalyst with little hope of ending until the momentum runs out. The concern for a democratic government is a balance of the people, which means that for people to be equally free and governed, all people need to be equal. Only then can we truly have a government “of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Works Cited

Brophy, James, Joshua Cole, John Robertson, Thomas Safley, and Carol Symes. Perspectives from the Past. 5. 1. New York: WW Norton and Company, 2012. Print.