- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Internal Roots of American Colonialism

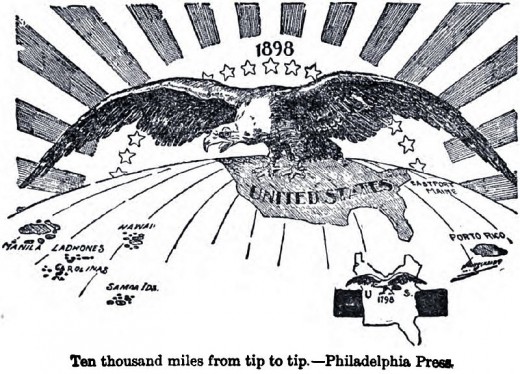

In 1898, the United States declared war on Spain, beginning a brief, 10-week “splendid little war” that ended the Spanish Empire in the Pacific and the Caribbean and brought US bayonets from Manilla to Havana. A decisive military victory, it left the United States with the question of what it was to do with the motley set of territories across the world that it had expelled the Spanish from, although not necessarily yet dealt with native nationalists and independence groups who were potentially hostile to US ambitions. Many of them would ultimately be annexed by the United States, forming an overseas empire for America which persists in part until today. In a stroke, the US had transformed itself into a colonial power, when it itself had once been born in the flame of anti-colonial revolution against the British Empire. For the United States, justifying this move required both a mix of common rhetorical tactics associated with empire, but also an insistence on the justice of American actions and its difference from the colonial expansion of the European nations which were carrying out their own empire-building at the same time. In this they were correct -- American empire was based not on radically new trends, but rather a continuation of the previous expansion across the continent brought overseas, with its differences stemming principally from the profoundly different challenges that Americans encountered rather than a dramatic difference in American mindset.

It can be easy, looking back upon the acquisition of American overseas colonial empire, to see it as but a brief and relatively unimportant passing phase. After all, the United States would only annex a scattering of overseas territories, such as Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Hawaii and various small islands. The jewel in the crown of the United States’ colonial empire, such as it existed, was the Philippines -- and yet the United States, despite waging a bloody war for its conquest, ultimately willing chose to give it up, even if it maintains a close and somewhat neo-colonial relationship with the country afterwards. Compared to the push west and the vast continental territories which the United States took, it makes for a measly and ultimately rather forgettable episode. And yet proponents of empire were far from seeing American colonial empire, conversely they saw it as part and parcel of the chain of US expansionism stemming from the Louisiana Purchase. Instead of seeing the conquest of the continental United States as being the end of American expansionism, writers such as Frederick Turner, publisher of the Frontier Thesis, argued that the virile energies of the United States would constantly demand wider fields for application. In the cultural realm, the conquest of empire overseas was associated with the march of empire at home. Thus, after the Battle of San Juan Hill, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show included it as a spectacle, just like it had previously included innumerable Western frontier battles.

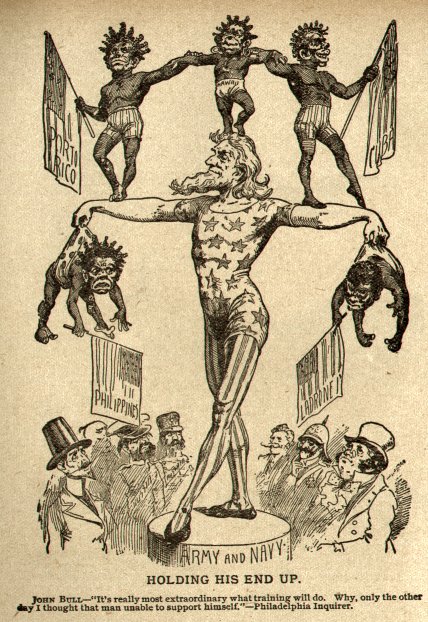

Racial Darwinism

Racist caricatures played an important role in American imperial expansion. Of course, there was nothing new in the utilization of racism, prejudice, and stereotypes to promote imperial expansion. European colonial expansion too was based upon the idea of the superiority of the white race, and of denigratory perspectives of the colonized peoples of the world. American characteristics however, were unique due a domestic element -- that representatives of overseas peoples colonized by the United States lived within the United States or had imagined corollaries. Thus Cubans became blacks like those of the United States, and Filipinos either blacks or Indians, playing into domestic themes of race. Unsurprisingly, when “civilized” Filipinos arrived in the US, they were perceived not in colonial terms, but rather as extensions of the same internal battle over race, as breaching the color line by pretending to some sort of equality with white Americans. Buffalo Bill sought to familiarize domestic American audiences with overseas races, just as he had done for the Indians previously, seeing the two as similar. In European nations of the time, racial images were of course present, but this internal menace was much less so. As an example, when American black troops or French colonial soldiers arrived in France in the First World War, they generally faced less personal prejudice (even if on an institutional level, the French were far from angelic), and during the Second World War English civilians resisted American efforts to impose the color line. Once more, it was American domestic sentiments that drove the perception and the creation of empire, rather than empire being a new phenomenon.

Social Darwinism

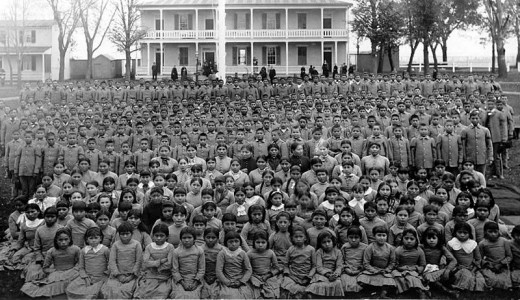

Social Darwinism was of course, also present in American visions of their new-found empire, portraying the colonized people they ruled over as inferior. But at the same time, the Americans had a long history of constructing relationships with the Native Americans internally that purported to civilize and uplift the Native Americans, while at the same time holding them as biologically inferior. To balance the difficult question of how to simultaneously present the colonized peoples as junior partners in colonization, as students in the great project of their civilizational uplift, while simultaneously also respecting knowledge, stereotypes, and prejudices of the inferiority of these very colonized peoples, was nothing new in the United States. Internally the United States had entertained extensive prejudices against the Indians, while also trying to educate them in boarding schools and positively describing the “uplifted” and newly educated Indians, to be used to assimilate the rest of their tribes to white standards. Many of the other thorny questions of empire -- native police, land policy, native scouts and auxiliaries, language policies, legal codes, and above all else military conquest, extermination, and pacification, had all been experimented with in the laboratory of the United States against the Native Americans. Empire within formed a laboratory and reference point for empire abroad.

Masculinity and Assimilation

These principles of Social Darwinism and racism also were closely tied with ideas of masculinity, the two being tightly intertwined in the late 19th century -- the idea that masculinity was a vigorous, brutish, powerful, aggressive force, the same as the higher races. Here once more, American empire found its reference point in regards to the frontier, with the publication of Frederick Turner’s “The Significance of the Frontier in American History”, which insisted that American virility and energy stemmed from the expansion of Americans across the continent, kindling their primal instincts and aggression. Unfortunately, this had run into the inconvenience that by the fin-de-siècle, the frontier no longer existed. Empire abroad thus represented an important replacement, which would enable a continued outlet and proving ground for masculine energy, a rhetorical argument which equated expansion with masculinity and anti-imperialism with decadence.

However, not all territories which were the object of the 1898 war with Spain were annexed. Nevertheless, in those territories where the United States did not formally assume control, such as Cuba, which was freed from Spanish colonial control after its lengthy revolt against Spain and then the following American intervention during the Spanish-American War, American imperialist attitudes or colonialist intentions were not absent, and these too had a relationship to the days of Manifest Destiny. As part and parcel of the American intervention in Cuba, the Teller Amendment forbid the United States from annexing the country outright. This would not be greeted with universal joy among American statesmen, many of whom wished to annex Cuba. To their credit, these statesmen did obey the resolution, and Cuba would never be formally annexed by the United States, but the desire to annex Cuba still led them to a very American belief -- that mass education and deeper knowledge of the United States would lead a colonized people to grow to love the United States, and in the case of Cuba, to join it. This too, drew its lineage from continental American practice with the Indians, where US boarding schools and education was supposed to en masse transform them into American citizens.

The Unique Nature of Americanization

Among most of the imperial powers, this was either only tangentially related concerning their their own education and colonial policies, or entirely absent. The Spanish made little effort to spread their own language throughout the Philippines, fearing that it would lead to rebellion and unity against them. The Dutch forbid instruction in Dutch and teaching it to the natives in many of their colonies. While most European powers did teach their languages and educate some of the colonized people they ruled over, they focused on a small elite which would be useful in their institutions and leadership, instead of on the popular masses. By contrast, the US was certain not only that education would be a vital tool to Americanize the territories which it had conquered, but convinced that this was a way to separate them from the European nations and their empires. It represents a remarkably different approach to colonization of overseas territories, and one which is based upon the different American experience concerning colonialism -- one developed by the US during its long record of internal colonialism against the Native Americans. Beyond taking the model as a whole of mass education from the Indian experience, they also took it directly as well, basing their education model very closely on internal education for the Native Americans. The other model which they drew upon was that of education for African-Americans within the United States. Once again, the United States drew upon its internal minorities to determine its external policies.

Of course, empire was not launched for reasons of simple allusion to the frontier, and there were genuine differences between empire abroad and empire at home. These differences are however, much less profound than one would imagine concerning their formation. The Spanish-American war was fought over Cuba, at its heart, and it was only incidentally that the many other territories which the United States would ultimately claim territorial dominion over were also involved. For the American public, the discovery that the United States was also involved in war in the Philippines and the global consequences of the war were revelations. The war over Cuba, while ultimately failing to produce the annexation of Cuba which many Americans desired, nevertheless involved American media portraying Cubans as a suffering, grateful, and white people, who would be eager to join the United States. It was Cuba, not the Philippines, which constituted the spark for colonial expansion, and if the United States hardly stumbled into ownership of the Philippines -- a vicious, multi-year guerilla war does not happen by accident -- it was a byproduct of this war rather than the reason for it.

The Siren call of Empire

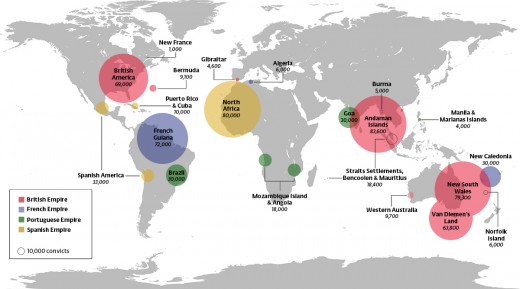

Even when the US did take the Philippines, there were plentiful calls to continue the work of empire just as had been done domestically. Harper’s argued that the boundary of oceans made no difference to US expansionism. Writers opined that the Spanish tolerance in the Philippines was a dreadful mistake by not driving the natives to extinction like the British in Australia and then proceeding to settle it via convicts. There were even plans to transform the Philippines into an American penal colony! Just like in the American West, these projects paid little attention indeed to the native people and the problem they posed for settlement, save for their extermination. The same could be said about junior projects in American colonial expansion -- there were proposals in the United States to form black settle colonies in the Philippines, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. Consistently, Americans launched themselves into the project of empire overseas and sought to continue it through the precedents established by their domestic empire. That they married it with new calls for markets and overseas trade does not detract from the peculiarly American intentions of empire.

Conclusion

American empire in the 1890s was in a geographic sense a dramatic change from its prior history. It differed markedly due to the conditions on the ground from the United States’ internal empire, but its developments were clearly defined not on radical new developments, but rather as an outgrowth of US domestic politics, and its justification, acquisition, and governance responded to internal American ideology. An elite project of colonial expansion, which brought benefits of new markets, naval bases, resources, and coaling stations had effectively constructed a link between it and the American expansion across the continent, while at the same time having the inescapable imprint of American imperial tradition placed upon it. This domestic laboratory for empire abroad distinguishes the US from the other oceanic empires of the late 19th and 20th centuries. These may have been impacted by internal politics and domestic concerns, but none had the example and the model of internal colonization and imperialism which the US drew on for its empire. It is this which would form the characteristic feature of American empire from 1898 onward, an empire from the homeland to overseas in a way like no other nation.

Bibliography

Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, “Nineteenth-Century Indian Education: Universalism versus

Evolutionism.” Journal of American Studies 33 no. 2 (1999): 323-341.

Kramer, Paul. “Making Concessions: Race and Empire Revisited at the Philippine Exposition,

St. Louis, 1901-1905.” Radical History Review 73, (1999): 74-114.

Martin, D. Jonathan, “‘The Grandest and Most Cosmopolitan Object Teacher’: Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West and the Politics of American Identity, 1883-1899.” Radical History Review 66,

(1996): 92-123.

Miller, M. Bonnie. “The Image Makers’ Arsenal in an Age of War and Empire, 1898-1899: A

Cartoon Essay, Featuring the Work of Charles Bartholomew (of the Minneapolis Journal)

and Albert Wilbur Steele (of the Denver Post).” Journal of American Studies 45 no.1

(2011): 53-75.

Mitchell, Michele. “‘The Black Man’s Burden”: African Americans, Imperialism, and Notions of

Racial Manhood-1890.” International Review of Social History 44 (1999): 77-99

Molin, F. Paulette, “‘To Be Examples To… Their People’ Standing Rock Sioux Students at

Hampton Institute 1878-1923 (Part One)” North Dakota History 68 no. 2 (2001): 2-23.

Paulet, Anne, “To Change the World: The Use of American Indian Education in the Philippines.”

History of Education Quarterly 47 no. 2 (2007): 173-202.

Pérez, A. Louis Jr., “The Imperial Design: Politics and Pedagogy in Occupied Cuba,

1899-1902.” Estudios Cubanos 12, no. 2 (1982): 2-19.

Pettigrew, John. “Brutes in Suits: Male Sensibility in America, 1890-1920.” Baltimore, John

Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Vaughan, A. Christoph. “The ‘Discovery’ of the Philippines by the U.S. Press, 1898-1902.” The

Historian 57, no. 2 (1995): 303-314.

© 2019 Ryan Thomas