Existential Psychotherapy, Viktor Frankl, and Jean-Paul Sartre - To Clear a Misunderstanding

Being an admirer of the existential tradition in psychology (particularly of the work of Dr. Viktor Frankl), I was eager to see how James Hansell and Lisa Damour, in their widely used textbook Abnormal Psychology, would portray it among the various theoretical perspectives. I suspected that it would be relatively marginalized, and it was; while eight pages were devoted to the biological perspective, six to the psychodynamic, four to the cognitive, and three pages to the behavioral, only a single paragraph was granted to the existential tradition. Although this bothered me, what bothered me far more was the way the perspective was not just marginalized, but marginalized to such an extent that I believe it was seriously misrepresented.

On page sixty-one, the text states that the perspective explains "psychopathology . . .based on [one's] inability to accept responsibility for creating one's own meaning in life." Next, it claims that existential therapies encourage clients "to face this responsibility" (p 61). On page fifty-two, the text lists the theorists who primarily developed the techniques used in existential therapy, listing Dr. Frankl among them. But nowhere is it suggested that Frankl himself (arguably the most important figure in the development of this perspective) would never have encouraged anyone to face the "responsibility" for "creating one's own meaning in life".

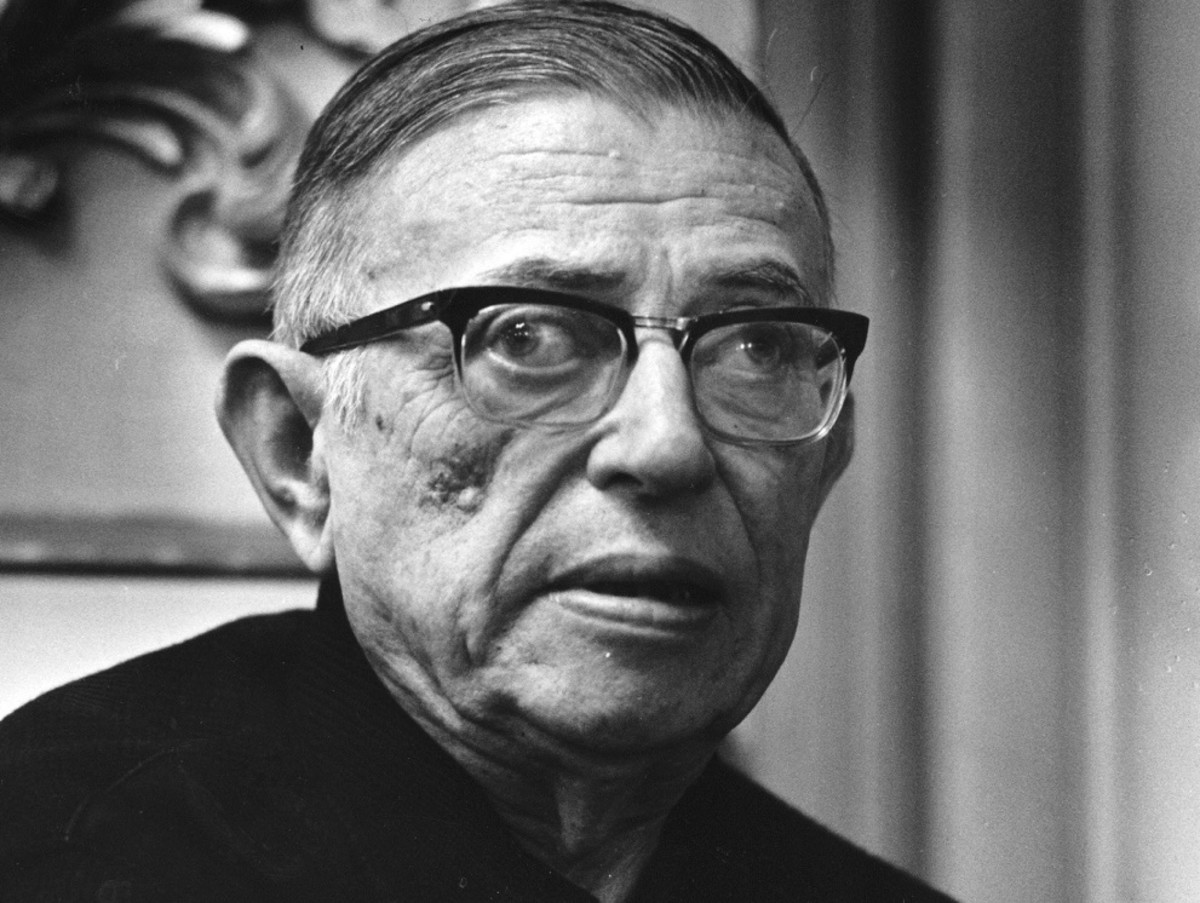

The philosophical concept of life's inherent meaninglessness and the resultant need for humans to "create" their own life meanings is indeed found within the existential tradition of Jean-Paul Sartre, but neither is this dogma a quintessential concept of existentialism, nor is Sartre the only important figure in the development of existentialist philosophy (Kierkegaard, for example, presents existentialism much differently). When the text, however, refers on page fifty-two to the "existential tradition" from which existential psychology draws, it cites only Sartre.

When Hansell and Damour overgeneralize existential therapy as encouraging people to be responsible for creating their own meanings, perhaps they rely too heavily on Sartre's conception of what existential therapy ought to be, found in his (cited by Hansell and Damour) Existential Psychoanalysis (1953). Sartre, however, was neither a psychologist nor a neurologist. Victor Frankl was both. The text's presentation may have been more nuanced if it had considered Frankl's Psychotherapy and Existentialism (1967), which states, "The meaning which a being has to fulfill is something beyond himself . . . only a meaning which is not just an expression of the being itself represents a true challenge" (p 11). Frankl further explains this, in The Unconscious God (1975 Edition):

". . .the 'to what' of all responsibleness must necessarily be

prior to the responsibleness itself.

What I feel that I ought to do, or ought to be, could never be

effective if it were nothing but an invention of mine--rather than a

discovery. Jean-Paul Sartre believes that man can choose and design

himself by creating his own standards. However, to ascribe to the self

such a creative power . . . is it not even comparable to the fakir

trick? The fakir claims to throw a rope into the air, into the empty

space, and claims a boy will climb up the rope. It is not different with

Sartre when he tries to make us believe that man "projects" himself . .

. into nothingness." (p 58)

I believe (although the scope of this article is far too limited to begin explaining), that therapy based on Sartre's perspective differs from therapy based on Frankl's perspective as night differs from day. If life has no meaning, attempting to discover one's meaning (as Frankl encourages) is an exercise in futility. If life has inherent meaning, any meanings that we merely create (as Sartre suggests) would border on the psychotic. Thus, Hansell and Damour's failure to delineate these radically differing views within the existential therapeutic tradition--one of the views being handed down by (in my opinion) the father of existential therapy--is an oversight that I consider tragic.