- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

The Murmansk Run

Hitler made the decision to attack the Soviet Union in 1941 based upon two assumptions: 1) the Germans would have success similar to that which they experienced in Western Europe; and, 2) as the German army moved into western Russia her industrial base would crumble as would her ability to wage war. At first it appeared Hitler had assumed correctly. The Russian army suffered defeat after defeat and their losses in lives and material were colossal. It was highly unlikely the remnants of their industrial base would be able to make up for all of the equipment being lost. Then a very early and extremely severe winter took hold. The Germans were ill-prepared and the first victim of the weather was their heavy armor; it was rendered virtually impotent. During that period they lost 75,000 motor vehicles and 180,000 horses. The Germans had lost striking power and mobility, yet the German High Command remained confident of victory. They believed the Russian losses were too heavy to sustain and they would be unable to resupply.

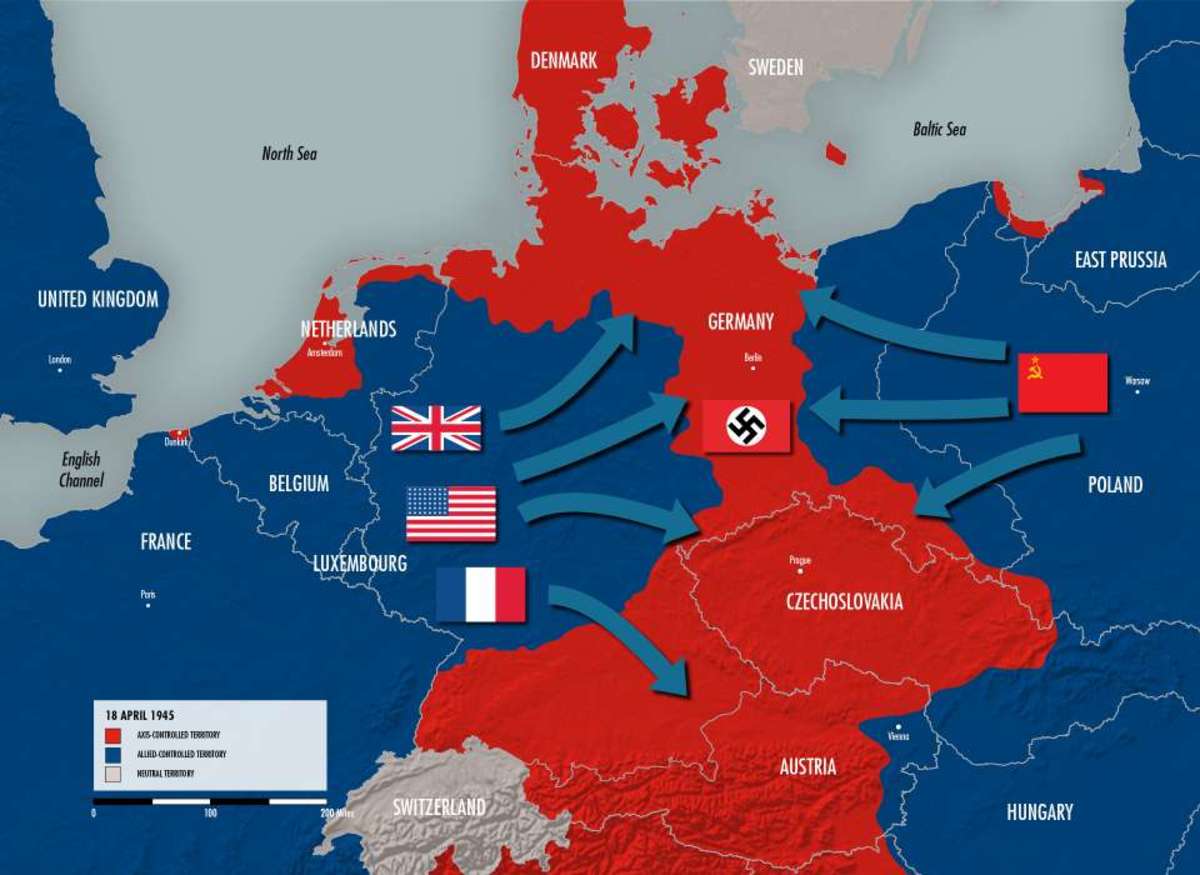

Four elements would combine to keep the Soviet Union in the war and Germany’s eastern front engaged: 1) the winter losses of Germany’s army had brought its numbers down to almost those of the Soviet army; 2) the severity of the winter gave the Soviets time to reorganize and plan counterattacks; 3) unbeknownst to the Germans, Stalin had begun relocating factories to eastern Russia and those factories continued to produce unabated during the German invasion; and, 4) the United States and Great Britain conducted a massive campaign to keep the Soviets resupplied.

Non-intervention

The U.S. had a policy of non-intervention prior to the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. Public sentiment essentially was that the war in Europe was a European problem and that America had no need to get involved. The American point of view was shaped by World War I and the effects of the Great Depression. President Roosevelt realized it was essential for the U.S. to become involved; he also realized Congressional and public sentiment was strongly anti-war in 1940-41. What he was able to do was get Congress to agree to supply the war efforts of those countries fighting Germany and Japan. Even then FDR had to campaign vigorously to get the aid agreed to. Congress wanted to know how the U.S. was going to be paid for all of the material being shipped to Europe and Asia. FDR likened it to your neighbor’s house being on fire. He said you lend your neighbor your garden hose to fight the fire; you don’t sell it to him. When the fire is out, he’ll return the hose. The vote in Congress fell along party lines and FDR signed the Lend-Lease Bill into law March 11, 1941 extending aid to Great Britain and by the end of the year it would also include aid to the Soviet Union.

The U.S. Merchant Marine

When one thinks of the great battles of World War II or the contributions of the various services to the Allied victory, the U.S. Merchant Marine is often overlooked. The U.S. Merchant Marine fleet constituted one of the most significant contributions made by any nation to the eventual winning of the war. It is arguable that without the resupply effort to Europe the war would have been lost.

There was no question that the shortest, quickest route to supply the Soviet Union was from the east coast of the United States, through the North Atlantic to the Russian port of Murmansk. Murmansk is located on the Barents Sea on the northern shore of the Kola Peninsula. It is the largest city north of the Arctic Circle. Murmansk exists because in World War I Russia needed an ice-free port that could be connected to the railway system and through which military supplies could be transported into the interior. In spite its geographical location, 124 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Murmansk remains ice-free year round due to the warming effects of the Gulf Stream.

A voyage to the northern shores of Russia was never a routine affair. Regardless of whether or not a ship faced enemy attack it still had to deal with Atlantic storms and the hazards of ice. From a day or two after departure a ship could expect submarine surveillance or attack at any point along the trip. Passing along the coast of Norway Allied shipping was in easy striking distance of German air bases spaced strategically along the coast. During the short summer period and 24 hours of daylight Allied shipping was a potential target from the air the whole time it was in range of the German air bases. The rest of the year they simply had to deal with some of the worst weather on earth; spray that froze on topside surfaces, blinding snow, driving sleet, and storms that scattered ships and broke up convoys.

Forty convoys, with a total of more than 800 ships, including 350 U.S. ships were on the Murmansk run from 1941 through 1945. Ninety-seven of those ships were sunk by either bombs, torpedoes, mines or the fury of the elements. They carried more than 22,000 aircraft, 375,000 trucks, 8,700 tractors, 51,500 jeeps, 1,900 locomotives, 343,700 tons of explosives, a million miles of field telephone cable, plus millions of shoes, rifles, machine guns, tires, and radio sets.

Of all the convoys that made the Murmansk run the one that is most often remembered is the PQ17. The PQ17 left Iceland carrying cargo worth $700 million loaded on 33 merchant ships and one oiler for refueling. These ships were escorted by three rescue ships, five destroyers, three corvettes, three minesweepers, four anti-submarine trawlers, two anti-aircraft ships and two submarines. The uniqueness of the PQ17 was that a large battle fleet of British and U.S. Navy ships were sailing on a parallel course. The plan was to lure the Germans into an uneven battle using PQ17 as bait.

The British Admiralty mistakenly believed the Germans were preparing to engage with naval strength superior to their own. British command could not afford the anticipated losses so gave the order for American and British ships to abandon the convoy to avoid heavy losses. The convoy was ordered to scatter and proceed to their destination at the utmost speed.

Of the PQ17, five destroyers were ordered to join the fleeing Navy ships and some of the escorts ran for safety while others attempted to help the merchant ships make the remaining 700 miles to port.

Between July 4 and July 14, 1942, German torpedo-bombers and U-Boats launched repeated, devastating attacks on the ships. The Germans wanted to stop Allied aid to the Soviets and believed one hundred percent annihilation of a convoy would be the answer.

Eleven of the 34 merchant ships reached Murmansk

Of the 215,000 U.S. mariners involved in the war, about 8,300 were killed at sea, 12,000 wounded (1,100 died from their wounds), 663 were taken prisoner. Thirty-one ships simply vanished without a trace. One in 26 mariners died in the line of duty, a percentage greater than the war-related deaths of all other U.S. services. Casualties were kept secret during the war in order to keep information regarding their success from the enemy and in order to attract and keep mariners at sea. In 1942 thirty-three Allied ships were sunk on average each week, but those numbers were never released until after the war.

Did the U.S. Merchant Marine win the war? No, no one branch of the service or no single engagement was responsible for victory. What the U.S. Merchant Marines accomplished by moving supplies and keeping Russia engaged with Germany on the Eastern Front enabled the other aspects of the Allied war effort to be more successful.