The Nazi Need for Race

In looking over the Nazi treatment of the Jews, many have felt that it all came down to racial hatred. They targeted a group that had been harassed for centuries.

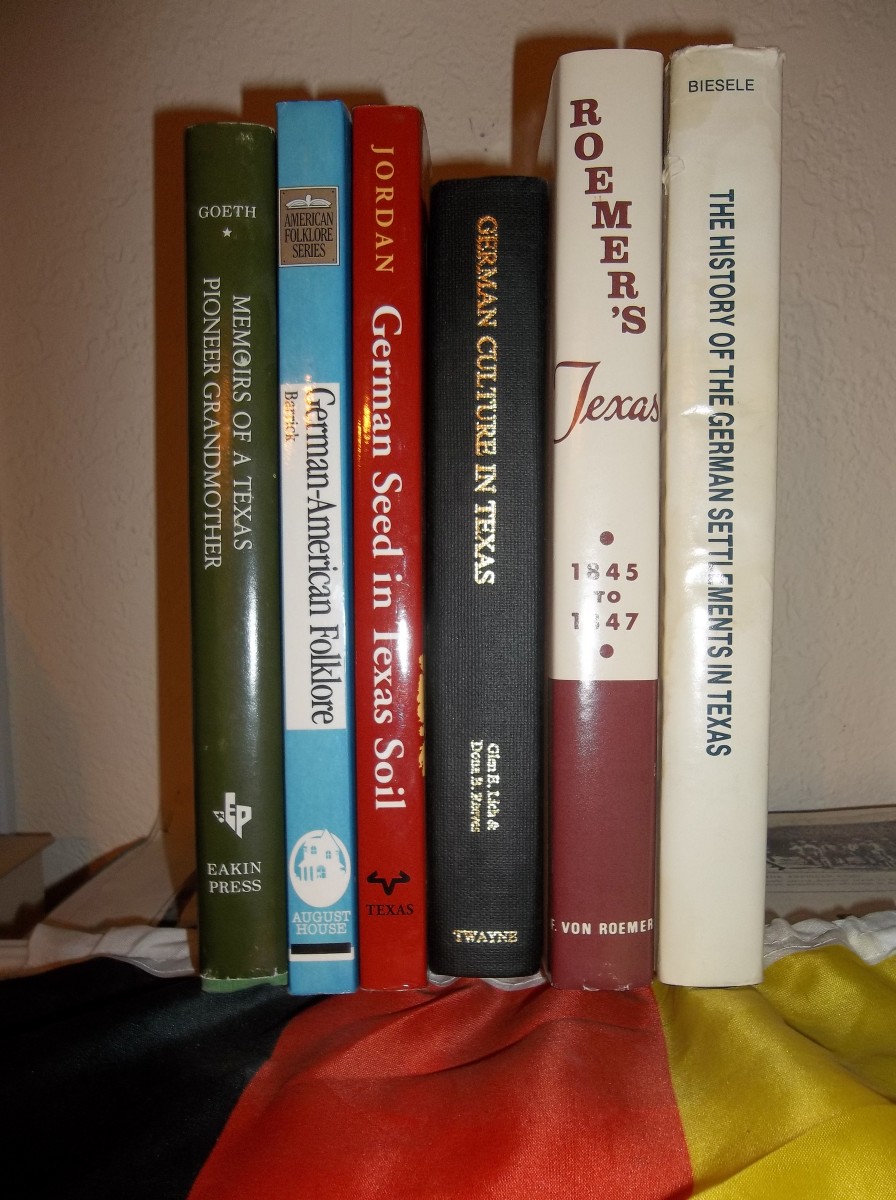

The Germans hated the Jews. Upon further analysis, the treatment is more a reflection of the German need to be unique and to be perfect. Germans needed to be all German. The Nazi party had to make race an issue to give themselves the foundation they needed to succeed.

Need for Identity

The Germans in the nineteenth and early twentieth century needed to have an identity. In that, they are not unlike other human beings on the planet. School children identify with their school colors or group’s image. To be part of something big and perfect is the goal of adults, too, as they take the banner of political, religious, and social groups. Germans wanted to feel special and clearly define what being German was.

On the surface, this sounds good, to establish pride in one’s country, but the path taken was to prove world-changing. It went beyond mere German pride. It went to the heart of the German people to not be ashamed of their heritage. The beating from World War I crippled the Germans emotionally.

Nothing New

The area that Germany occupied was historically an area of political disharmony. It was under Bismarck in the 1800s that unity was finally achieved. To many, including Bismarck, success had been achieved.

Though it was very successful in meeting the goal of Bismarck, many within Germany’s borders could only see how much more could be done. They saw how much bigger Germany could be. Many wanted to be successful in “precisely defining Germany.” They wanted areas on the outskirts of the country to be included. A clear definition of what it meant to be German was needed.

Defining Germany by Blood

In the process of defining Germany geographically, the minds of many within Germany began to wonder if the definition of Germany was much deeper than that. Was being German more than living in a certain area? Throughout Europe, races were mixing with a focus more on the unity politically as well as geographically. Lines of distinction were getting fuzzy.

Some saw nationality as something that could easily be changed as nothing could actually “prevent him leaving one nationality and deciding to become part of another one.” By moving to one country and adopting the culture, religion, and traditions one could easily become French, English, or Spanish. That was why man Jews called themselves German. They had lived in the area for a few generations. Being Jewish was more a religion and culture than a nationality to many.

Many within the Nazi party saw nationality as being in the blood. It was more than what a person was at that moment. Being German involved generations of history as well. You had to be German since the beginning of time.

It's All in the Blood

The Nazis began looking at genealogy. It was not to discover ancestors as more to discover where those ancestors came from. One drop of blood that was not Germanic was considered to be tainted. Even it was seven generations earlier, one could not have any African, Jewish, or Native blood.

The goal was racial purity. Race was not narrowed from human race to ethnic targeting. This allowed them to exclude many unwanted people.

Finding a Home

There was no country of Israel at this time. The Jews could not claim a motherland. They could be found in practically every country of the world. Taking this absence of a home into account made the Jew appear below the German or anyone else who could claim a homeland. They were nomads or gypsies, wondering with no roots to cling to.

To some, this stance was moot if the Jew was willing to adopt core Germanic principles such as the Christian religion and patriotism for the German country. Moving into a country and assimilating was not uncommon. By becoming “German”, there was no debate of race. Yet, many kept bringing up this subject. The idea of the blood became more prominent and was used to incite fear in many.

It did not matter if they were German, they were still Jewish. They needed to find a home.

Source:

Schleunes, Karl A. The Twisted Road to Auschwitz: Nazi Policy Toward German Jews 1933-1939. Chicago: University of Illinois, 1990.