- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Nez Perce

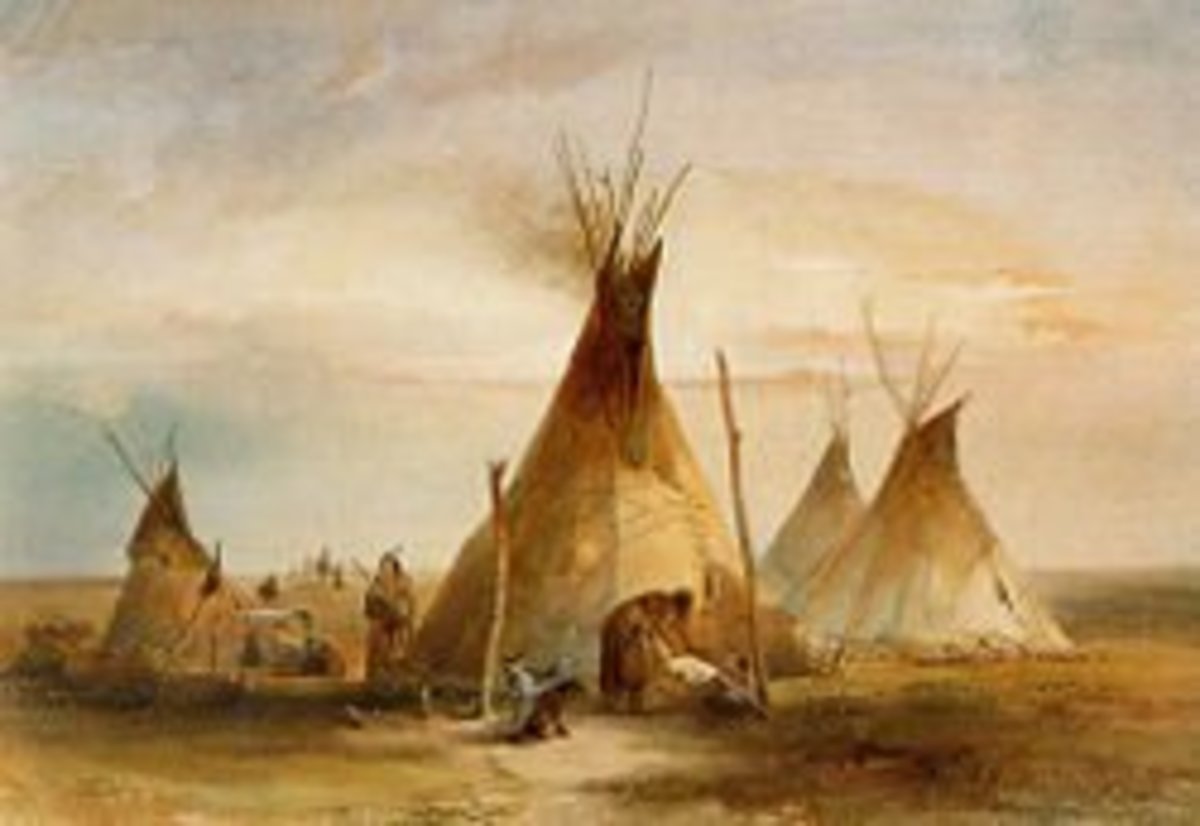

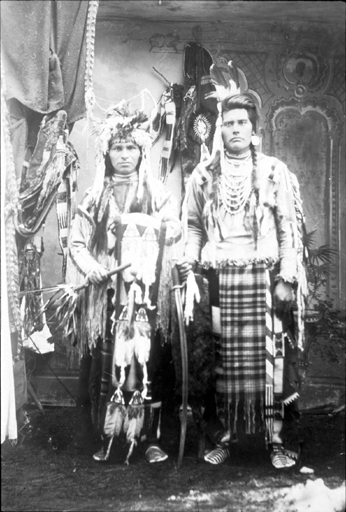

Long before the Western trinity of guns, germs, and steel swept across a New World, the Nez Perce of the Plateau lived scattered along a landscape of yawning canyons, flowing rivers, and sudden elevation shifts. Their territory, which stretched across central Idaho, northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington, allowed for a semi-nomadic lifestyle, dependent upon the seasonal location of food sources. They were thought the preeminent group in intertribal relations on the Plateau, as evidenced by the use of the Nez Perce language in economic and political situations across the region.

While unified under a tribal name, a visible division existed between the Upper and Lower Nez Perce. The former generally resembled a Plains life-style more so than the latter, a differentiation attributed to dialect of speech. Either division managed to retain a cultural and social connection with the Sahaptin speakers of the southern Plateau, who have been identified as having a close linguistic relationship to the Nez Perce.

The Natives of this region extracted a number of plentiful resources from their surroundings. Throughout the spring, during which the river valleys were settled for the duration of several months, hunting of small and large game animals such as rabbit, badger, deer, and elk was pursued via employed methods of trapping, ambushing, and deadfalls. While offering to sustain the population throughout the year, hunting although did not engage the same extent of manpower as that attributed to the salmon runs.

Enhanced by progressive fishing technologies that included lines, spears, harpoons, and dipping nets, thousands of pounds of fish were captured annually. Those acquired by the fall salmon runs, during which the Nez Perce inhabited the highlands of the Plateau, received proper curing and were stored. Additional surplus included late yielding crops as well as roots, berries, nuts, and seeds, all gathered in preparation for winter, when a sedentary lifestyle was adopted, until the early days of spring.

The semi-nomadic lifestyle revealed through the subsistence pattern of the Nez Perce featured band level organization of villages lying near tributary systems that came to identify them. These villages, which commonly included semi-subterranean housing, a sweathouse, and menstrual hut, comprised extended families who were overseen by the eldest male, chosen either by council for his generosity, war lust, or shamanistic powers, or assumed a hereditary position stemming from a well established lineage. These leaders then attended to the needs of his community, serving in roles such as spokesperson or moral guide to those within his care.

The headman of the largest village further assumed the role of bandleader, thereby guaranteeing membership into a composite band council, which organized cooperative ceremonies, economic practices, and most importantly, defense. Unification only extended to this composite band level. The Nez Perce did not become a singular entity under a head chief until after 1830, and this only under terms that were dictated by the progression of historical events.

Life among the inhabitants of the headman’s village was a seemingly well-socialized and traditional existence. Grandparents readily accepted the role of rearing Nez Perce children who, through them, would be introduced to the basic tenants of life and guided through pre-adolescent years. Youths enjoyed integration into subsistence responsibilities at an early age and were conditioned in their gender roles, such as hunting for boys and rooting digging for girls, that upon maturation would become expected behavior.

Ceremonies, which were generally performed in temporary, mat-covered longhouses, marked the major watersheds of an individual’s life and were celebrated at times when, for instance, the first child of a union was born, a young boy trapped his premier animal, or a girl experienced her first menstrual cycle. Perhaps the most profound of these traditional milestones occurred around the period of adolescence, when a child was required to elicit a vision from a tutelary spirit, which, if achieved, would prompt a successful and prosperous future for the concerned youth.

Marriage was another highly celebrated transitional period in life. Whether pre-arranged or self-motivated, a pre-nuptial process comprised of negotiations, lineage assessments, and feasting proved a requirement in order to assess the compatibility of the concerned match. A marriage was sanctioned only after the second of two gift exchanges between the families of the betrothed concluded. Sororal polygyny was a regular practice, and while divorce was easily obtained, it remained discouraged.

While the adherence to traditional practices generally suggests some form of social cohesion, it is evident that perhaps the overall solidity of Nez Perce society was steadily challenged by individual conflicts concerning respect, wealth, and authority. The practiced religious system encouraged the pursuit of power, a necessary path believed to have to be taken in order to surpass a standard existence and achievable only through the assistance of great shamans. The epitome of attainable power given to an individual by tutelary spirits was granted in the form of song during adolescence and publicly recognized by the community during spiritual events such as the winter tutelary spirit dance.

Power acquired through spirits often manifested itself through sorcery, a significant component of Nez Perce social control. Through belief in the supernatural capabilities of an individual, all manner of transgression, including disrespect or failure to fulfill a social obligation, could be punished without immediate consequence. Besides curing the stricken and affording relief to those suffering, the abilities of a shaman to exorcise and heal those afflicted by sorcery served to weave him into the social fabric of society beyond his usual responsibilities of sustaining the seasonal religious ceremonies.

Yet, these seemingly primordial traditions of the Nez Perce were not immune to the rapidly transforming state of the world. While the economy was the initial area to become subject to external forces via Euro-American fur traders by 1811, the prime territory of culture soon thereafter fell victim to the invasion as well, but this at the hands of missionaries. In only a short span of time, a people defined by their polygynous marriages, fervent beliefs in the supernatural, and cultish ceremonial practices, became adherents of Protestant theology, adopters of horticulture, and literate Bible readers.

The adoption of a Christian life was not without costs. Horrific epidemics eradicated a large amount of the Nez Perce population, whose estimated number of 6,000 individuals was reduced to a meager 1,800, while internal instability based upon either the following or avoidance of the Protestant presence further decimated any social unity that may have remained. The treaties of 1855, 1863, and 1868, which divided and distributed Native land to non-Native populations and maintained for Christian governance over remaining Nez Perce territory, provided only further realization of what penance must be paid in order to successfully co-exist with Western society.

The only form of mass-resistance ever attempted by the Nez Perce stemmed from its non-Christian sect, which steadfastly refused further infringement by White pioneers, consequently spurring a conflict known as Chief Joseph’s War. The result of this three-month engagement was the surrender of over 400 Nez Perce and the further entrenchment of Christian based rule and Euro-American culture on what remained of the tribe’s reservation, which was but a small acreage of land that, by 1895, was being allotted to non-Native American settlers.

Fifty years would pass before the Nez Perce would again adopt a system of self –governance, free of Presbyterian influence and based upon ancient tradition. The Tribal Executive committee and other councils established during the mid-1900s severed any remaining ties that may have linked hopes of existence with assimilation. Instead, focus was concentrated on educational, housing, and legal programs directed at reviving and re-inventing the economic and cultural practices of an earlier time.

Copyright Lilith Eden 2011. All Rights Reserved.

Most of my information was gathered from the Handbook of North American Indians (Deward E. Walker, Sturtevant, William C., Walker, Deward E., Jr.).