The Origin of Democracy

Primitive Societies

It could be argued that democracy is in fact the most basic form of government. When a small group of people, perhaps even prior to the Neolithic Revolution, functioned as a society, it follows logically that decisions would be made communally by way of discussion among members. With the growth of populations in these communities, however, oligarchy and autocratic forms of government developed for obvious reasons of practicality. Gathering hundreds or thousands of individuals to make communal decisions would quickly become impractical if not impossible.

Mesopotamia

Evidence exists to suggest that pre-Babylonian Mesopotamia may have been ruled by a proto-democratic system in which power resided with free adult males in the form of councils rather than in an autocratic society where authority resides with a king or similar figure.

Arguments against this theory state that this form of government is more similar to an early oligarchy than democracy, They cite the fact that while this system suggests a wider-spread influence among the citizens of a community, it does not necessarily state that power resides with all free people but rather an aristocracy of sorts. Still, this theory does suggest a dispersal of power in early forms of government, which was prone to develop in smaller rural communities.

Greece and Early Democracy

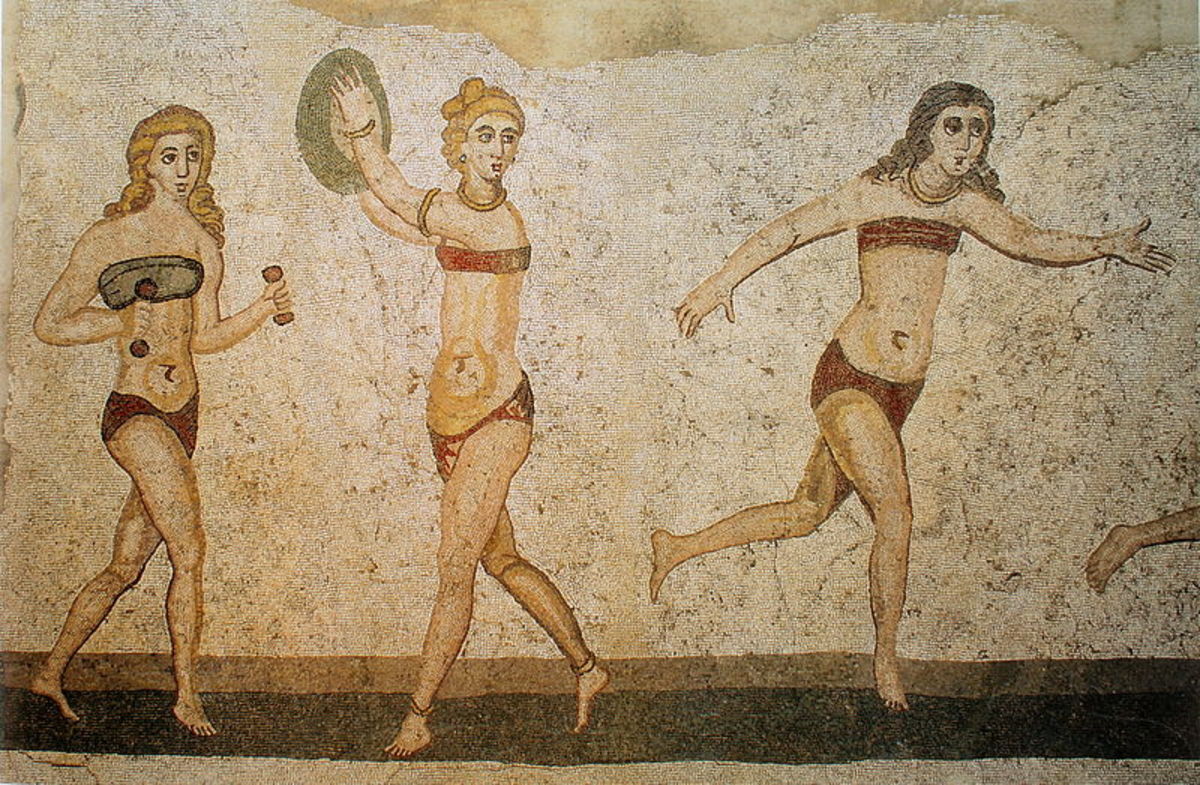

Some historians argue that the roots of democracy in Greece reside not in Athens but their rival state, Sparta. Though in broad strokes Sparta was an oligarchy, the structure of their government was unique and bore striking resemblances to the accepted definition of democracy.

The Spartan government consisted of two kings, who were included in a larger council of elders , as well as ephors, a small representative group who oversaw the kings and elders. Most critically in this context, however, was the apella. This assembly of all male Spartans over the age of 30 elected all officials excluding the kings and voted to approve or deny the proposals of the elders. This system bears a remarkable resemblance to the modern concept of democracy.

Ecclesia

Ecclesia in Athens was the popular democratic institution in which all decisions of policy were made. It was opened to all male citizens of Athens with at least 2 years of military service, and dates back in this form as far as 594 B.C., at which time Solon opened it to all Athenians, regardless of social or economic class.

Athenian Democracy

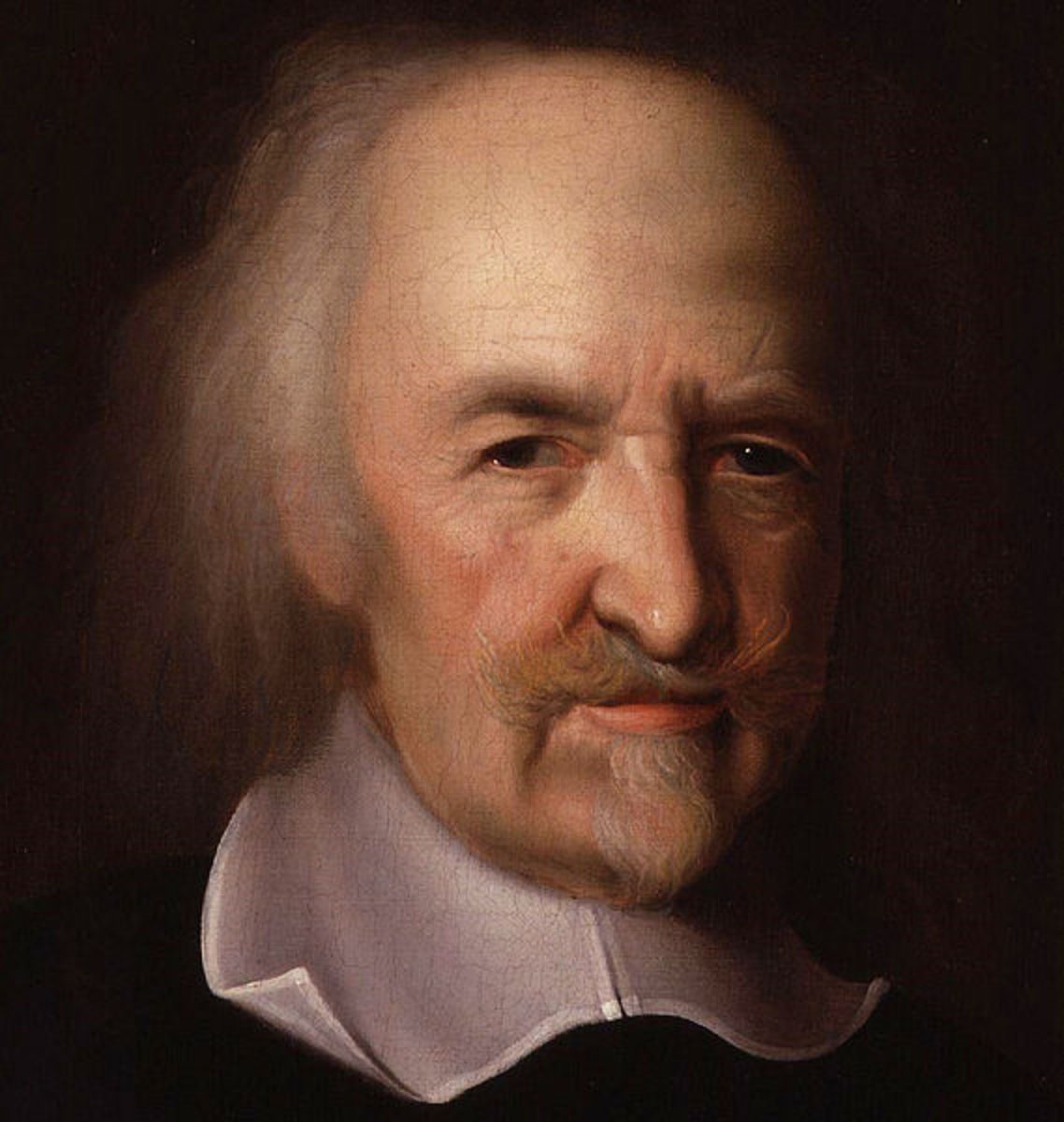

The opening of the Ecclesia to all Athenian classes is credited to a lawmaker and statesman named Solon, effectively establishing the foundation of Athenian democracy in response to the disposition of the previous tyrannical system in archaic Greece.

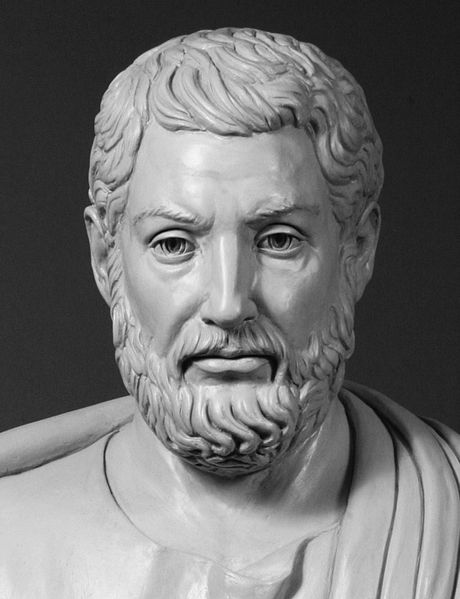

The first mention of democracy in Athens came under the reforms made by Cleisthenes around 508 B.C. The term, meaning "rule by the people", was used in this period to describe a system of government developed following the removal of the prior tyrannical system. This new concept restructured the society of the city-state and granted rights of equality to all. Further, it expanded ruling class by giving access to authority to a broader range of Athenians.

This concept was further defined by Pericles and Ephialtes, who once again restructured power in Athens in response to the demand of the bottom classes for say in their own government. The resultant system decided election of major officials by lottery, and these officials oversaw the operation of the government.

All major decisions in policy were made by majority vote in Ecclesia, in which any adult male Athenian could participate. This aspect of the Athenian system is a direct democracy in the truest possible sense for the circumstances, considering that thousands of Athenians could conceivably have participated at any given time.