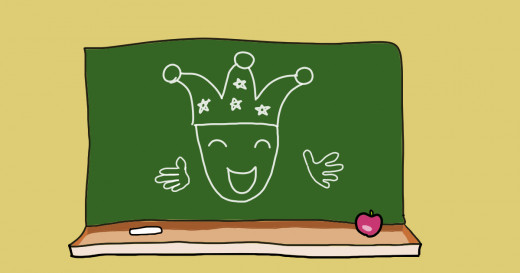

The Playful Magic of Humor in Education

Have you ever noticed that the best comedy shows don’t just make you laugh, but also blow your mind? Perhaps you’ve caught yourself saying, “That’s so true!” or “Wow, I never thought of it that way before!” In other words, the humor taught you something new.

Humor is deeply linked to learning. Both involve making connections between separate ideas. Moreover, humor has emotional benefits – such as enjoyment, enthusiasm, and relief – that make it easier to learn.

The possibility that humor could help education is why I started this blog. ProvocaTeach is founded on the view that we could use more humor in education, along with its cousins play, spontaneity, wit, and creativity.

I hope to convince you that mixing humor with education isn’t like mixing bleach with vinegar. There will be no poisonous effects or nasty surprises. On the contrary, a humorous classroom is an ideal worth striving for – one that opens new possibilities for students’ learning and well-being.

Humor for learning

Humor as a form of play

There are many theories of humor, but the one I like best sees humor as a form of play. When we play, we re-interpret or imitate otherwise serious situations in enjoyable ways (Moeller & D’Ambrosio, 2017). Humor fits this definition well.

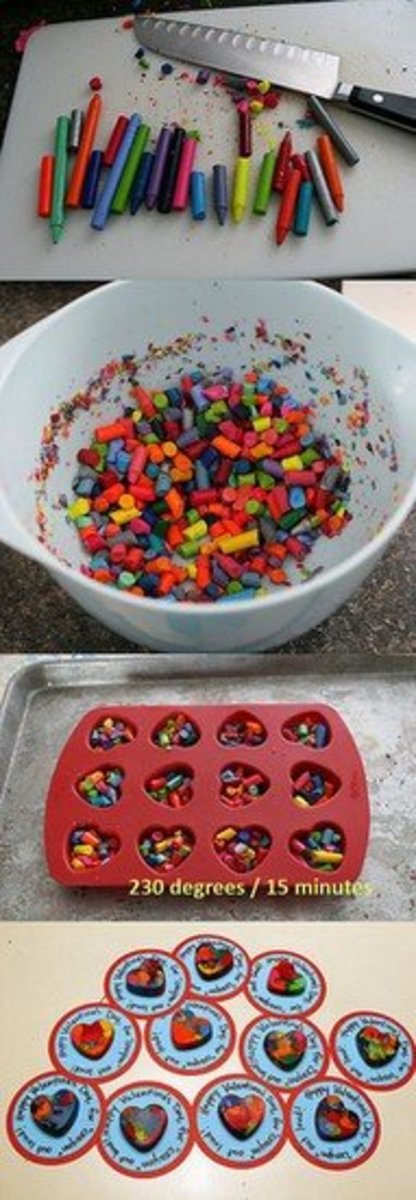

Play and humor are both ways of “trying on” new roles. A young child might play the role of “pet owner” by pretending to walk a dog. He might use his hand to hold an imaginary leash, or stop to let the imaginary dog sniff around.

Play helps the mind grow

Play is magical in its ability to create something out of nothing. It prepares us for new situations without directly exposing us to them.

Make-believe play teaches children how to plan, self-monitor, and reflect (Bodrova, Germeroth, & Leong, 2013). For example, a group of children playing “surf contest” might:

-

choose the surfers;

-

choose the announcer;

-

decide what the waves are like today;

-

set the rules of the contest.

They can simulate all of this and learn social skills without entering the water. (The only thing they won’t learn is how to surf!)

Witty humor connects ideas

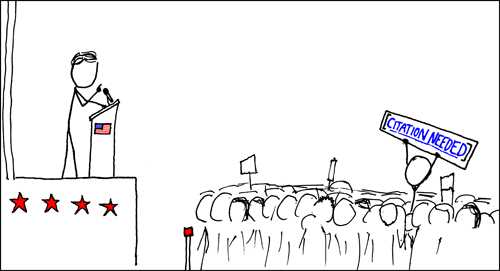

Not all humor has equal educational value. The jokes that belong in the classroom connect seemingly unrelated ideas in clever ways. James Geary (2019), in his book on wit, put this as, “In poems, words rhyme; in puns, ideas rhyme.” (p. 10)

The first stage, connecting seemingly unrelated ideas, is purely creative. It is unstructured and occurs in a part of the brain known as the “default network”. The second stage organizes those connections into a witty remark. This stage takes place in the “executive network”, the part of the brain responsible for working memory, planning, and inhibition.

But “finding connections between seemingly unrelated ideas” is not only useful in humor; it’s also the definition of discovery! And the second stage, verbalizing those connections, is the essence of academic communication.

Thus, engaging students in witty conversation has tremendous educational value. It trains their minds to take successful creative risks and communicate the results – two highly sought-after academic skills.

Humor to relieve pressure

Moral and social pressure

School can be a stressful place. With adults and peers telling them what to wear, say, do, and think, students bear the weight of social and moral pressures.

These pressures can negatively affect their academics. Many students, for example, do not volunteer in math class because they fear the shame of being wrong.

However, by telling a well-placed joke or two, the teacher can loosen these pressures somewhat. Humor that is used to relieve social and moral pressures is referred to as carnivalesque (Moeller & D’Ambrosio, 2017), after the carnival tradition born in the Middle Ages.

Is humor immoral?

The Medieval carnivals were not concerned with following the moral and social norms imposed by the religious orthodoxy of their time. In other words, the humor was amoral; it was independent of morality. The value of carnivalesque humor lies in its ability to relieve the stress of moral fear.

However, the church saw the carnivals as not merely amoral, but immoral – that is, wrong. Similarly, when a student tells a joke in the classroom, it is often treated as immoral. At best, the teacher tries to move on quickly; at worst, the student gets punished.

Nevertheless, the function of humor in the classroom need not be immoral; the amoral aspect is what provides the main benefit. Lifting moral and social pressures frees students to play with ideas in creative and potentially-disrespectful ways. This affords new possibilities.

Conclusion

While there is a place in the classroom for morality, moral and social fears can get in the way of students’ creativity. By creating space for relevant and witty humor in education, teachers can lessen moral and social pressures. This can have a strong impact on school climate, improving students’ well-being.

I can’t promise your students’ standardized test scores will shoot up. But if you’re looking for something to care about, consider humor in education. Every student can benefit from cracking a smile.

References

Bodrova, E., Germeroth, C., and Leong, D.J. (2013). Play and Self-Regulation. American Journal of Play 6(1) 111-123. URL: eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1016167

Geary, J. (2019). Wit’s End: What Wit is, How it Works, and Why We Need It. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, NY. URL: jamesgeary.com/wits-end

Moeller, H. and D’Ambrosio, P.J. (2017). Genuine Pretending: On the Philosophy of the Zhuangzi. Columbia University Press, New York, NY. URL: cup.columbia.edu/book/genuine-pretending/9780231183994