- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Asia

The Sino-Japanese War: A Short Historical Analysis

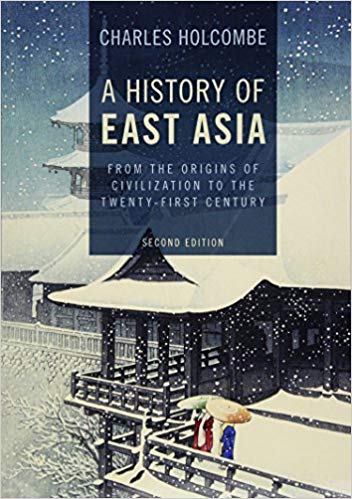

Charles Halcombe's A History of East Asia

The Sino-Japanese War: A Short Historical Analysis

The relationship of China, Japan, and Korea in the late 19th Century was centered in a power struggle between China and Japan, over the control and influence on the Korean peninsula. The conflict saw China’s status as a regional power challenged by Japan, and its subsequent decline after its defeat in the hands of the Meiji led Japanese government.

How It All Began

Before the onset of the Sino-Japanese War, China was considered as the dominant power in the Asian region with vast controls of land, political, and military influence; with Korea as one of its important “client” or tributary states. However, in the 1850s, Chinese influence under the Qing Dynasty experienced a power decline after a series of defeats (e.g. First Opium War against the British Empire) and rebellions. These events weakened the military and political influence of the Chinese in the Asian region. Such was so, that it created a power vacuum which encouraged growing powers like Japan to step up and assert its dominance in Asia.

Japan on the other hand, has seen the decline of the shogunate period and its isolationist policies. It instead gave rise to the Meiji restoration of 1868, which restored and centralized the practical rule of Japan under the Emperor Meiji. The restoration consolidated the political system to the Imperial household and changed the former feudal state into a modern industrial state, which leaned toward westernization. The new Meiji government oversaw numerous reforms to its political, economic, and military structure. It further assimilated western culture by sending representatives abroad to study and adopt western concepts and technologies. These actions and events brought about by the reform altogether strengthened the political, economic, and military capability of Japan.

The Korean Corridor to China

Korea, which had been for a time an isolationist state, finally opened its doors to foreign commercial trade and western influence after the Ganghwa Treaty of 1876 with Japan, and the establishment of diplomatic ties with the United States in 1880. However, even with the steady adaptation of western culture and technologies, Korea still did not have the capability to sufficiently defend itself against foreign invaders. This in turn worried Japan, as Korea is near Japan and is considered as a strategic entry and exit point to and from Japan. The then Meiji government expressed growing concerns over the threat to the national security of Japan, should the volatile Korean state be invaded by foreign powers. To combat this and to protect Japanese interests, the Meiji government chose to adopt a passive reform policy to Korea and encouraged the latter to model and liken its reforms to that of Japan.

After the events of the 1882 crisis, or the so called “Imo Rebellion” in Korea, efforts to continue reforms were thwarted and the Chinese were able to reassert their dominance over the country. This laid the groundwork for the Chinese and Japanese conflict over the control of Korea. The struggle’s focal point was mainly on the Chinese intent to retain control over Korea, versus Japan’s push for reforms in the Korean peninsula.

Which Drew the First Blood?

Various ideological differences and disputes of national interests led to the degradation of Chinese Japanese relations. One of the first issues which ignited conflict between China and Japan is when: “In 1884, pro-Japanese Korean reformers initiated a coup d’état to overthrow the Korean court and establish rapid reforms in the country. The plan was however thwarted by Chinese General Yuan Shikai which resulted in the death of Japanese legation guards in the process. Further hostilities between Japan and China were only avoided through the Tientsin Convention, which is also called the Li Ito Convention. Under the convention, both parties agreed to withdraw their troops from Korea” (www.britannica.com, 2018).

On March 28, 1894, a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary named Kim Ok Gyun, which was also a collaborator in the 1884 coup, was assassinated in Shanghai; to which the Chinese then extradited said body to Korea where it was cut, quartered, and displayed in all Korean provinces as a warning to supposed rebels and traitors. This occurrence outraged the Japanese government and furthered tensions with the Chinese.

The final string which worsened Sino-Japanese relations and subsequently started the war was the Donghak rebellion in Korea. According to historical references: “Upon the onslaught of the Donghak rebellion, King Gojong of Korea requested aid from the Qing government to eradicate and control the uprising. The Chinese accordingly sent General Yuan Shikai with troops to Korea. This action however was seen by the Japanese as a violation of the Tientsin Convention. The Japanese countered by also sending troops to Korea” (www.newworldencyclopedia.org, 2018). The Chinese then tried to further reinforce their troops in Korea, but the British steamer Kowshing which carried the reinforcements was sunk by the Japanese, which further aggravated the situation.

After a breakdown of negotiations between the involved parties, and King Gojong’s rejection of the Japanese reform proposals, Japan on July 23, 1894 invaded Seoul and established a pro-Japanese government in Korea. War was finally declared on August 1, 1894 between Japan and China.

The series of battles thereafter saw the spontaneous and continuous defeat of the Chinese, whilst the Japanese made steady advances. By August 4, the Chinese forces were pushed all the way back to Pyongyang in a defensive posture, while the Imperial Japanese Army advanced to the Chinese positions from multiple directions. The Chinese losses were further exemplified after the defeat of its Beiyang fleet, the capture of Port Arthur, Shandong province, Manchuria, and fall of Weihaiwei. The Chinese, although numerically superior in terms of military manpower, was plagued with corruption, and poor training within the ranks of its military. These shortcomings, as opposed to Japan’s newly modernized and westernized Imperial Japanese Army under the Meiji reforms, contributed greatly to the strategic defeats of the Chinese.

After the overwhelming losses against the Japanese, the Chinese government sued for peace. The official end to the Sino-Japanese war came in the form of the Shimonoseki Treaty: “Said treaty which ended the conflict, saw China’s recognition of Korea’s independence, and cession of Taiwan, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaodong peninsula to the Japanese. Apart from this, China was also forced to pay huge reparations for the war damages. Japan was however forced to return the Liaodong peninsula to China, after the joint intercession of Russia, France, and Germany” (Watanabe et.al., 2019).

Conclusion

To summarize, the events of the Sino-Japanese war saw the shift of power move from China to Japan. The results effected the decline of China and the rise of Japan as the dominant regional power of the period. Sources state that: “China’s defeat at the hands of Japan in the Sino-Japanese War, irrevocable shattered its traditional sense of self-assurance, and what remained of the pre-modern Chinese world order was rapidly undermined thereafter” (Holcombe, 2018). With the string of defeats, China became more vulnerable to western exploitation and demands as its political influence and prestige was badly damaged. It was henceforth no longer able to assert itself as effectively as it did during the peak of its dominance in the Asian Region. Korea through the conflict, gained independence but was still under Japanese Influence. Its political structure was also still considered to be weak relative to that of Japan and its other neighbors due to the preceding events which destabilized its government. Japan on the other hand began to be recognized by western powers as a formidable authority in the Asian region and began its rise as a global power way towards the end of World War II.

References

Holcombe, Charles. (2018). A History of East Asia : From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press, 2011. books.google.com.

“First Sino-Japanese War.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 25 Jul. 2018. Web. 27 Oct. 2018. <https://www.britannica.com/event/First-Sino-Japanese-War-1894-1895>

Watanabe, Akira, et al. (2019). “The Emergence of Imperial Japan.” N.p. https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan

Foreign Affairs.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 25 Oct. 2018. Web. 27 Oct. 2018. < https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan/The-emergence-of-imperial-Japan>

"Donghak Peasant Revolution." New World Encyclopedia. Creative Commons Corporation, 13 Oct. 2017. Web. 27 Oct. 2018. <http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Donghak_Peasant_Revolution&oldid=1007236>