The Spread of Gold.

The Spread of Gold

“once extracted from the earth it can be made into artefacts or coins, melted down again, turned into bars or jewelleries, sold, smuggled, looted or stolen; changing its appearance but retaining its essential character.”

Gold mined in the Ashanti forest 300 years ago, carried to the coast, shipped to London, turned into English guineas and passed down again from hand to hand for decades, then melted down again, may today form part of an Indian bride’s dowry. Because of its remarkable anonymity we cannot always tell where any particular piece of gold began its journey, although we can get a broad idea of how gold has spread around the world since it first began to be valued.

Throughout history, gold has been moved across the world, its presence indicating power, and its absence decline and defeat; and gold, in this context, cannot usually be divorced from its use as money. Although some groups, such as the Ashanti, continued to use gold dust as currency until this century, most of its monetary use has been in the form of coins.

The invention of coins, quantities of metal of fixed mass and of agreed value, is attributed to the Lydians, Greek inhabitants of what is now western Turkey, some time late in the 7th century BC.

Creating coins was a revolutionary step, making all sorts of exchanges easier and quicker. Virtually everything that could be counted, measured or weighed could also be given a value measured in coins. This enabled sellers to hold on to the value of what they sold until the time was ripe for them to take other items in exchange for it. Once coins had been “invented”, much of the world’s gold and silver was destined to be used in this form.

The earliest coins were made of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, but the first pure gold and silver coins are traditionally ascribed to Croesus of Lydia (561-546 BC), a ruler who is said to have sent 3,400kg (7,500 lb) of gold to decorate the temple at Delphi, Greece. Gold coins, however, were comparatively rare in the classical world; they were normally outnumbered by silver, which was more readily available, or by bronze. The Athenians for example, only minted gold coins in an emergency, stripping gold from statues to do so. As Greek power expanded, more gold was coined.

In the 4th century BC, Philip of Macedon obtained enough gold for the regular minting of gold coins; his son Alexander the Great, was able to greatly extend the area in which gold coins circulated, having seized the hoarded gold treasures of the pharaohs and the Achaemenids of the Persian Empire and gained control of gold sources farther east.

Gold coins were rarely struck under the Roman Republic but Imperial Rome began to use them. The gold solidus struck by the emperor Constantine remained unchanged in its weight and purity until the Empire itself disappeared. Many of the gold coins made under the Empire, however, seem to have been traded out of it into India and the far east.

Travelling East.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire gold coins tended to disappear from circulation, for the most part being replaced by silver coins debased to varying degrees. One problem was that the West was short of gold. The contrast with the Islamic world was striking. In the 690s the caliphate started minting a gold coin that was soon to be accepted from Spain to Malaya. This was the dinar, its name derived from denarius aureus, the gold solidus coin of the late Roman Empire. The dinar set the standard for purity and wide acceptability for centuries to come: it penetrated into Christian Europe, sometimes continuing to be used in trade, sometimes turned into jewelleries and ornaments. The abundance of gold in Islamic countries had a great deal to do with their access to the gold producing areas of West Africa. The great network of overland trade routes from those areas existed largely to pump gold into the Islamic countries where dynasties like the Almoravids of Morocco minted it into dinars.

West African gold sometimes came into circulation outside Africa in more direct ways. When the great king of Mali, Mansa Musa, who ruled between 1307 and 1332, made the pilgrimage to Mecca, he took 500 slaves with him and so much gold, that after he left prices in Cairo took three years to get back to their old levels.

Gold coins clearly carried a high level of prestige. A country minting gold indicated both wealth and stability, allowing it to command easier trade terms simply because people trusted the purity and constant weight of its coinage. Thus the revival of the European economy in the 13th century was signalled by the reappearance of gold coins. The emperor Frederick II, for reasons of prestige, issued gold coins in 1231. In 1252, Florence issued fiorino d’oro, or florin, and Genoa the genovino d’oro. Venice issued the ducat in 1284, France had gold coins by 1330, and the English noble dates from 1351. Some of this gold must have been obtained from Islamic countries by trade, possibly in exchange for silver, a metal Europe had far more of, and some probably came from new gold mines in Hungary.

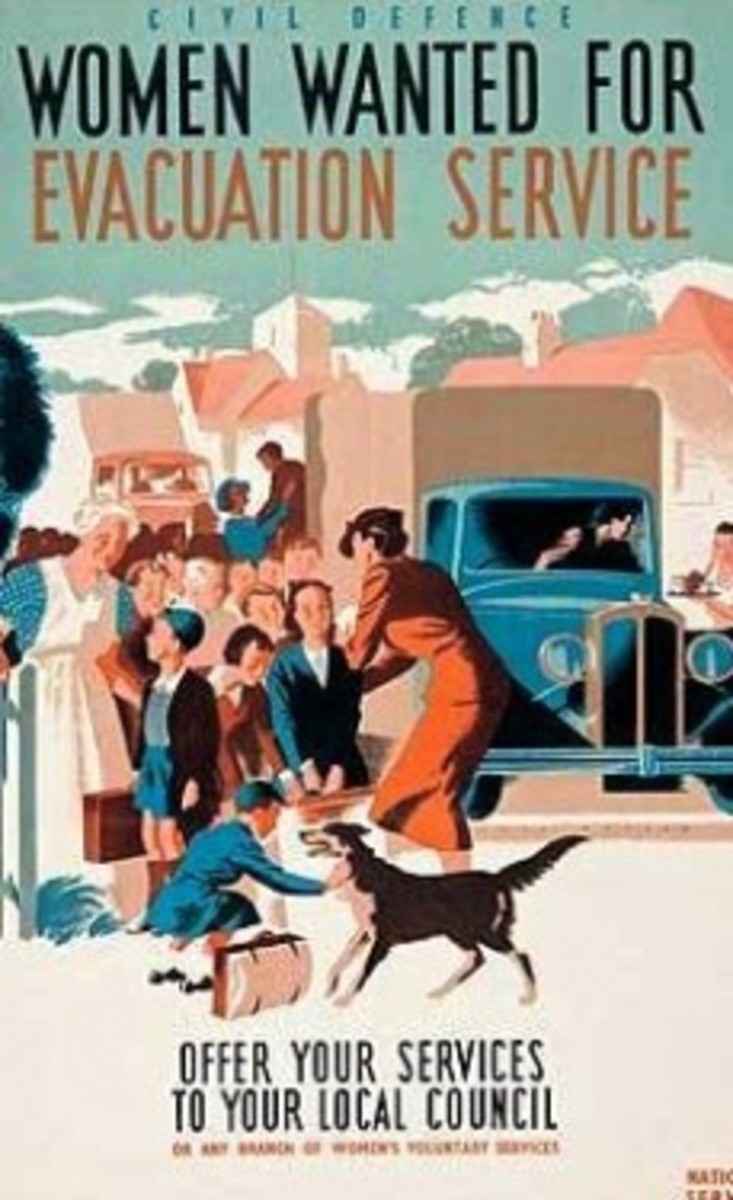

THE SILENT TRADE.

The movement of Europeans around the world from the 15th century on, aided by their increasingly efficient sailing vessels with unprecedented firepower, caused major changes in the movement of gold and an increase in its circulation as coins. The Portuguese, for example, captured the North Africa coastal town of Ceuta in 1415 and learned from the Moors of gold rich lands on the Upper Niger and in Senegal. This was the era of what has been described as “silent trade”, when the Moors trading with the Akans who occupied present day Ghana, obtained large quantities of gold (as well as slaves, ivory and pepper) in exchange for iron, pewter basins, brass, pots, pans, knives, dagger and salt. Until the 19th century, salt was a particularly important item for barter in West Africa. Indeed, one gold-producing forest tribe was so much in need of it, they were willing to exchange salt for gold, weight for weight.