The Emergence of Nuclear Power and the Meltdown at Three Mile Island: March 28,1979

Three Mile Island

Minutes from Disaster

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 was a significant turning point in the evolution of nuclear energy within the United States over the next thirty years. This legislation shifted the onus of nuclear energy development from the military to civilian control, assigning it to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The AEC assumed the role from the Manhattan Engineer District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had secretly developed the atomic bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki under the top-secret Manhattan Project.

The project was designed to bring an end to the Second World War. It involved research and production at more than thirty sites across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, with an adjusted cost of 14 billion dollars in today's currency. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) launched the development of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. Following this, the AEC approved the construction of over a hundred commercial nuclear power plants throughout the United States.

Industrial powerhouses General Electric and Westinghouse were in competition for valuable contracts to construct nuclear power plants. The Atomic Energy Commission promised the American public that nuclear power would provide a cleaner, safer, and more efficient way to generate electricity. By March 1979, the construction of forty-seven nuclear power plants across the United States heralded the beginning of a new epoch in economical energy generation.

In the early hours of March 28, 1979, progress was halted abruptly on an island in the Susquehanna River near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The incident at the Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear power plant marked a pivotal moment in the history of American commercial nuclear power. Following the significant Three Mile Island incident, the construction of nuclear power plants in the United States came to a standstill. The Three Mile Island accident was rated as a level five event, defined as an "accident with wider consequences," on the seven-point International Nuclear Event Scale.

Less than three weeks after the release of the Hollywood epic "The China Syndrome," the most severe nuclear accident in the history of American commercial power generation occurred. The Three Mile Island incident echoed scenes from the film, which depicted Elliot Lowell, a physics professor, as an opponent of nuclear power generation.

Lowell claimed that overheating of the fuel rods in a nuclear reactor's core might cause them to melt through the plant's floor swiftly. Such an event could lead to an explosion, dispersing a deadly radiation cloud over the northeastern United States, possibly causing millions of fatalities and making the region uninhabitable for thousands of years.

The choice of Pennsylvania for comparison by Lowell was indeed a strange coincidence. The Three Mile Island incident became a major international event due to mistakes, oversight, and poor decision-making at various levels. Today, the cooling towers of Three Mile Island serve as a stark reminder of the potential dangers inherent in the production of nuclear energy.

The Three Mile Island incident commenced around four o'clock in the morning on March 28, 1979. A substantial leak of coolant water occurred due to an open valve in the recently constructed Unit 2 reactor. In the following two hours, operators misinterpreted the signals, neglected to close the valve, and erroneously deactivated the automatic emergency cooling system, leading to the overheating of the reactor core. By the break of dawn, America was facing its gravest nuclear crisis.

For nearly a year, the TMI nuclear power plant quietly generated electricity on an island in the Susquehanna River. Located just ten miles from Harrisburg, the state capital, it was also only 100 miles downwind from the major metropolitan areas of Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington D.C.

In the early hours of Wednesday, March 28, 1979, the exposed core of Unit 2 at Three Mile Island began to overheat, reaching temperatures above 4,300 degrees Fahrenheit—merely 1,000 degrees away from meltdown. Plant operators scrambled to stabilize the escalating reactor core. News of the incident first reached the public via a local radio station broadcast.

Lieutenant Governor William Scranton announced to the public that Metropolitan Edison, the owner of the plant, had the situation under control and that no radiation had leaked from the facility. Yet, upon departing the podium, Scranton learned that radiation had, in fact, been released and resolved to no longer rely on Metropolitan Edison for information regarding decisions.

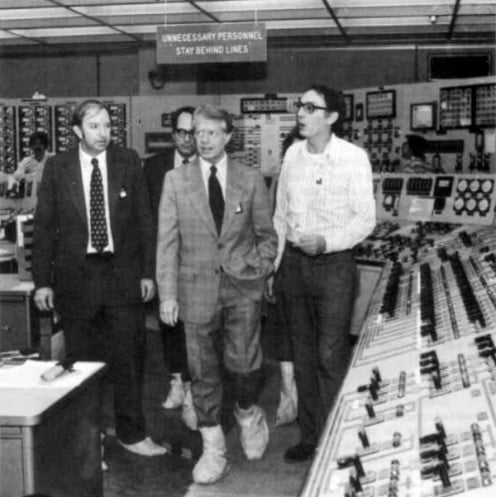

Carter Visits Three Mile Island

Meltdown

The events that transpired over five days at Three Mile Island would go down in history as scientists hurried to avert a meltdown disaster. Government officials swiftly intervened to assuage public fears, leading to the evacuation of thousands to emergency shelters around the facility. The crisis peaked when The Associated Press issued an urgent bulletin about the potential explosion of a hydrogen bubble in the compromised reactor. The local residents experienced intense anxiety as the situation escalated.

The U.S. Department of Energy has outlined a worst-case scenario to state officials, suggesting that an explosion compromising the containment vessel could release fatal radiation levels. A state official has forecasted "extremely high" radiation dose rates, potentially reaching thousands of rems per hour. Such exposure would be fatal for residents near the plant, as a dose of five hundred rems per hour is deemed lethal.

President Carter visited Three Mile Island (TMI) the Sunday following the incident to assist in crisis management and calm public concerns about the facility. As an ex-nuclear submarine officer, Carter probably had a more profound grasp of nuclear reactor operations than any other president before or after. His examination of the plant's damage showed significant courage.

At the news conference in Middletown following the tour, Carter implored the public to stay calm in the event of an evacuation. His visit signified the crisis's conclusion. Subsequently, scientists confirmed the reactor core's stability, leading to the gradual return of residents to their homes. Despite assurances of minimal radiation release during the incident, the event sustained lingering skepticism within the community for years to come.

Three years post-incident, a robotic camera provided the first glimpse into the core of TMI Unit 2, revealing the extent of damage from the 1979 event. Roger Mattson, a senior engineer at the NRC, informed the public, "We experienced a meltdown at Three Mile Island. The core was partially destroyed or melted down, with roughly twenty tons of uranium settled in the bottom head of the pressure vessel. It was undeniably a core meltdown." Although a considerable amount of radioactivity was released from the reactor, the majority was contained. The cleanup effort, costing over one billion dollars, continued until 1993, culminating in the removal of the last hazardous materials from the site.

Clean Up

The Clean-up and Cover-Up

The term "Big Lie" is associated with claims that the radiation releases at Three Mile Island were "insignificant." However, the stack monitors designed to measure such radiation were overwhelmed and rendered nonfunctional. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) conceded to Congress that it did not know the quantity of radiation released or how it dispersed. Despite initial claims, melting did occur within Unit 2's reactor core. Later inspections by robotic cameras disclosed that a considerable part of the fuel core, amounting to twenty tons of uranium, had melted down.

The public was initially told that evacuation was not needed. Nonetheless, Pennsylvania Governor Richard Thornburgh ordered the evacuation of pregnant women and young children from the area surrounding Three Mile Island. Unfortunately, a number of evacuees were sent to nearby Hershey, which was also affected by the fallout. In hindsight, a prompt evacuation of the entire region would have been prudent.

The government had assured the public of comprehensive studies on the health histories of local residents. Despite Pennsylvania's state authorities hiding the health impacts, the evident tripling of the infant mortality rate near Harrisburg remained conspicuous. The government issued average radiation dose estimates received by residents, claiming them to be safe, even in the absence of verified data on the levels of radiation released.

The estimates were dismissed, partly because they did not account for the potential impact of high doses of concentrated fallout on specific areas. Official statements equated the exposure for everyone in the region to that of a single chest x-ray. Yet, it is widely recognized that pregnant women are not subjected to x-rays due to the established risks that even one dose can pose to an embryo or fetus in utero.

The most credible studies were carried out by locals such as Jane Lee and Mary Osborne, who conducted door-to-door surveys in the areas most affected by the fallout. Their findings showed a significant occurrence of cancer, leukemia, birth defects, respiratory issues, hair loss, rashes, lesions, and other serious health conditions. Historical records suggest that the local populace within a 10-mile radius of Three Mile Island suffered severe effects.

Numerous central Pennsylvania residents experienced sunburns, skin sores, and lesions while outside during the fallout. Many quickly developed large, visible tumors, had difficulty breathing, and described a metallic taste in their mouths, similar to those who witnessed the Hiroshima bombing and were exposed to nuclear tests in the South Pacific and Nevada, known as atomic soldiers. Studies by Dr. Stephen Wing, an epidemiologist from the University of North Carolina, and others, significantly challenge the official government account of the radiation emissions and their health impacts.

Arnie Gundersen, a former nuclear industry executive and nuclear engineering expert, has stated, "My accurate analysis of the containment pressure spike and the environmental dose measurements after the Three Mile Island incident indicates that the releases were about a hundred times more than the industry and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) have acknowledged, partly because of leakage from the containment vessel."

It is recognized that containment vessels can experience leakage through the various pipes and electrical conduits that penetrate their walls. Due to the high cost of sealing these penetrations, federal regulators allow a certain level of leakage.

Some experts have suggested that the radiation released at Three Mile Island could have been up to a thousand times greater than the figures reported by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). This discrepancy has sparked debate over the prudence of allowing the construction of such facilities, considering the possibility of radiation leakage from structures designed to confine it.

Living with Nuclear Power

Can we believe?

The Three Mile Island nuclear incident marked a pivotal moment in the development of nuclear power plants in the United States. After the incident, the issuance of new permits for constructing nuclear power plants ceased. There is a hope that the United States will follow Germany's lead in decommissioning all nuclear power plants and pursuing alternative electricity generation methods to avert irreversible environmental harm.

Ironically, Three Mile Island Unit 2 was considered a state-of-the-art reactor, similar to Chernobyl. It commenced operations on December 28, 1978, and experienced a meltdown precisely three months afterward. If it had been operational for a longer period, the radiation emitted from its core might have been substantially more. The "Big Lie" is still officially upheld.

The Three Mile Island incident is often termed a "success story" because there were no immediate fatalities. However, the reactor, once valued at $900 million, quickly became a multi-billion-dollar liability. Currently, all active reactors in the U.S. are significantly older, and more than thirty years have passed since the meltdown at Three Mile Island's Unit 2. The potential consequences of a similar event today could far exceed those of the 1979 incident.

Highlighting the gravity of the crisis faced by the residents of central Pennsylvania, the renowned CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite commented after the Three Mile Island incident, warning that "the world has never known a day quite like today."

The incident confronted the substantial uncertainties and dangers of the most severe nuclear power plant disaster in the atomic era. The alarming truth is that conditions could worsen. If Three Mile Island were to happen today, we would have a data center with advanced capabilities to assess any damage or risk.

The event prompted the creation of a specialized unit within the Department of Energy, focused solely on simulating the potential risks of fine particles from nuclear fallout or chemical blasts as they spread through the environment. The National Atmospheric Release Advisory Center, situated at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, acts as our protection against nuclear and chemical incidents or attacks.

The system was implemented in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island incident. Throughout the crisis, determining the exact quantity of the released radiation—which was tasteless, odorless, and invisible—or its drift direction was unfeasible. The sensors designed to monitor radioactive emissions were overwhelmed, and the plant's existing instruments were insufficient for the scale and scope of the release that transpired at Three Mile Island.

Intermittent releases of radioactive gas surged into the sky, veiling the aftermath, and the events that transpired on the Susquehanna River in the early hours of March 1979 may never be fully understood. The Three Mile Island incident continues to be enveloped in secrecy, forever relegated to the domain of the unknown.

Sources

Gray, Mike. The Warning: Accident At Three Mile Island A Nuclear Omen for the Age of Terror. W.W. Norton & Company Ltd. New York. London, Castle. House, 75/76 Wells Street London WIT 3QT. 1982

Walker, Samuel J. Three Mile Island: A nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles & London., 155 Grand Ave Ste 400, Oakland, CA 94612. 2004