Tiny Houses: A Short History

Homes steadily increased in size during the last half of the 20th century and a vibrant economy was created around home construction industry. But not everyone was ultimately charmed by the notion of home ownership and the debt attached to it -subsequently binding them to creditors - nor being forced to depend on utility companies for services required to maintain a home. Proliferate zoning laws, property taxes and high costs of repair and maintenance detract from the benefits of owning a modern style home as well. More square footage also means that ownership requires more time spent in upkeep – time taken from what is little available to most workers on the weekend. A tiny home, while sacrificing space, also makes up for it in energy saved by having to clean and organize less.

A discussion of the tiny house movement must include the recent proponents and builders belonging to the trend, those who lent tremendous momentum to the growing fervor over tiny houses – homes under 400 square feet. A rediscovery of small house living synchronically took flight in the late 1990s concurrent with the beginning of the housing boom and rapid rise in traditional home prices. Susan Susanka was one of the first to champion the purpose and design of tiny houses having published her book The Not So Big House in 1998, wherein she discusses how to live better and build better by downsizing. She in turn was influenced by Christopher Alexander, an Austrian architect who proposed the existence of a universal system of building that could be adapted to any size in the book A Pattern Language, published in 1977.

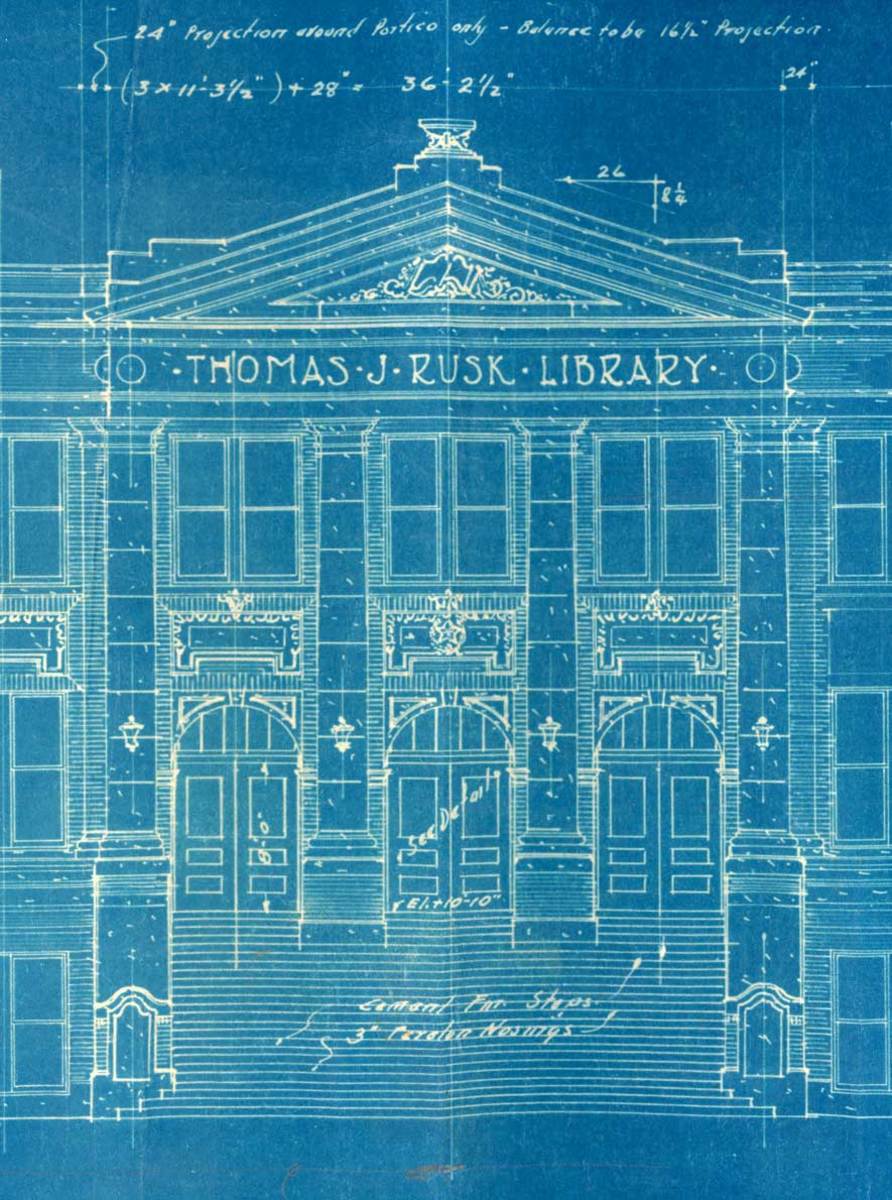

It was in an organic way that the tiny house movement gained popularity in the months after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 when the city of New Orleans had to deal with finding housing for displaced people. FEMA trailers were problematic and so as a response to this, architects such as Marianne Cusato were hired to design and build small cottages that reflected the vernacular of the region. Most of Cusato's blueprints are for homes larger than the tiny house standard, the smallest model is around 310 square feet and the largest at big as 1800 square feet. Needless to say, the Katrina Cottage or "Cusato Cottage" solved the housing problem. And blueprints for the cottages are nowadays selling wildly.

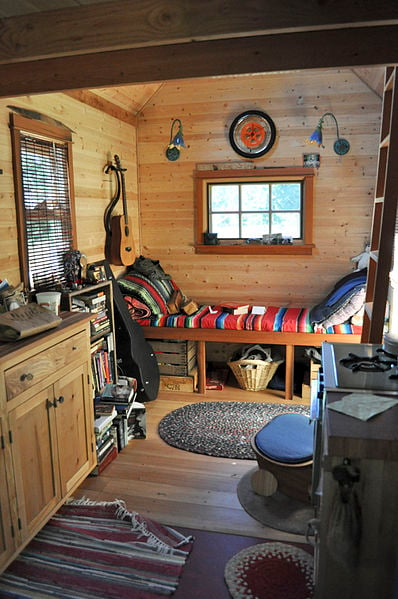

In 1997, a tiny house innovator named Jay Shafer built and moved into a tiny house and from that grew his building company called Tumbleweed that has since become well-established and renowned. Shafer has written prolifically on the subject of tiny houses and guided other small home builders through their own tiny home building process. He has left Tumbleweed to start Four Lights Tiny House Company. Another well-known tiny home proponent and consultant is Dee Williams who with Joan Grimm runs an endeavor called Portland Alternative Dwellings through which tiny home workshops are conducted. In 2004, Williams sold her conventional house in Portland and built and moved into an 84 square foot tiny home. Ten years on, she is the author of Go House Go and is widely regarded as one of the foremost experts on tiny house building. But Williams and Shafer haven’t been the only ones building small homes in years past.

The tiny house movement of today seems to have revisited ideals and practices of the counterculture and activism of the 60s and 70s. Hippies went to live in communes, what might be called "intentional community" now, and lived apart from society in settlements incorporating structures like yurts, tents, abandoned buses, and even domes. These structures were built by hand and in isolated areas beyond the reach of conventional housing laws, building codes, and public power and water, so experimenting with living in alternative dwellings was possible. Authors Art Boericke and Sammy Shapiro produced a book on construction in 1973 called Handmade Houses: A Guide to the Woodbutcher's Art with designs and advice regarding self-built small homes. In 1979, Artist Jane Lidz published Rolling Homes: Handmade Houses on Wheels - a rare and coveted book that surveys 70s Era portable homes like converted school buses or gypsy wagon style rolling trailers (the same type that inspired the design of tiny homes on wheels produced by Tumbleweed and other companies).

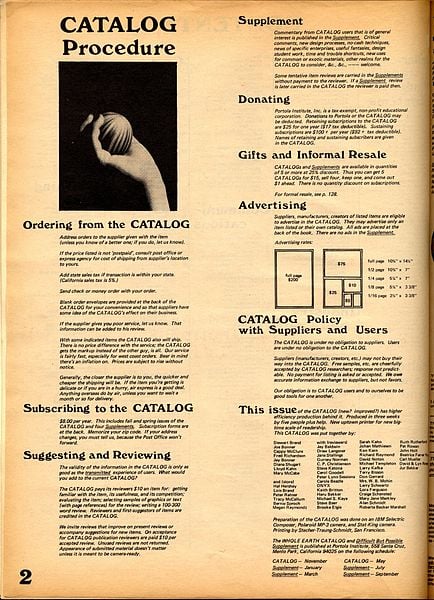

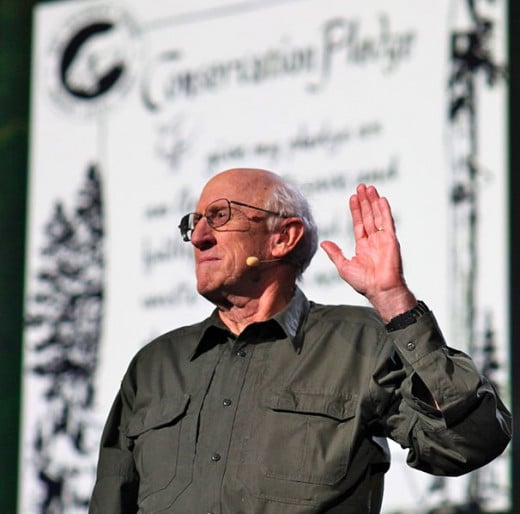

Stewart Brand, author of the Whole Earth Catalog published between 1968 and 1974 (then sporadically through 1994), promoted self-sufficiency through knowledge of building and tools, and green living through which self-sufficient harmonious community could be built.Lloyd Kahn was co-editor of the section on shelters in the Whole Earth Catalog and undertook extensive experimentation on building small sustainable dwellings including some dome houses. In fact, in 1973 Kahn published a book called Shelter, a guide to small dwelling types around the world. His recent book, and popular reference, called Tiny Homes: Simple Shelter was published by Shelter Publications, a company he owns. Both Brand and Kahn owe something to mid-century American philosopher and architect Buckminster Fuller who advocated inexpensive and sustainable pre-fabricated housing as demonstrated in his design of geodesic structures sometimes called Fuller Domes. In fact, his Dymaxion house built in 1929 (an example of which sits in the Henry Ford Museum) is an early example of an autonomous house, a completely self-sustaining or “off-the-grid” dwelling – a sort of prototype for today’s tiny home.

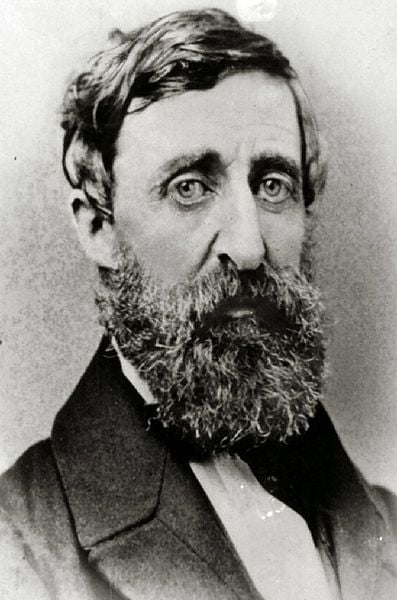

The story of tiny home would not be complete without mentioning the early Americans who were familiar with living in small dwellings that befitted a homesteader’s life - families resided comfortably in cottages, cabins, sod house, and more miserably, tenement housing. Immigrants to America gladly relinquished old world possessions for the promise of freedom even if that meant building by hand their one room shanty in the wilderness. Autonomy and intrepidity will always be a uniquely American solution to feeling oppressed whether by the British or by debt and recession. Some credit is also due 19th century writer Henry Thoreau and his iconic book Walden in which he sketches a bucolic picture of a simple life in a small cabin. It doesn’t seem a coincidence that Thoreau’s embrace of civil disobedience in protecting individual rights reflect the inherent feel of the small house movement in its passive resistance to widespread mortgage debt and dependence on public utility.