- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Underground Railroad: A Code of Secrecy, Part I

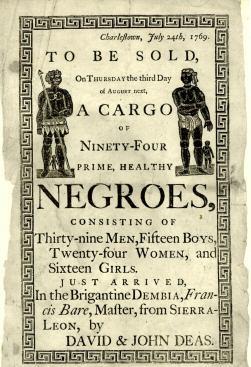

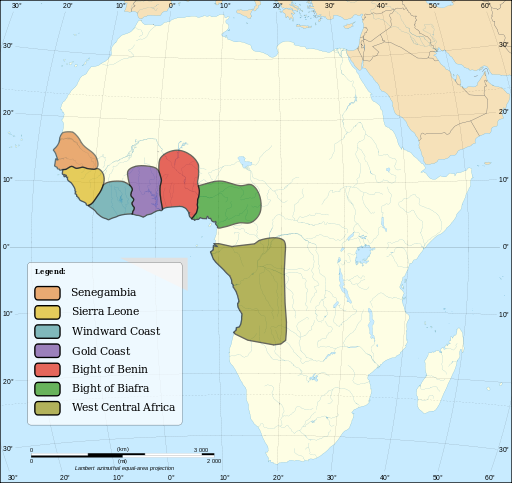

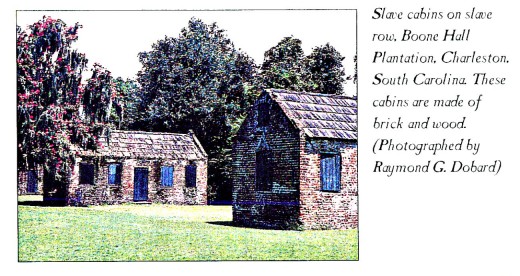

Almost four hundred years ago, approximately, four million African men, women, and children were among the slave population in America. One of the first points of entry for these enslaved Africans was Charleston, South Carolina, a place where they once out-numbered the white population four-to-one. Their journey to America had originated in one of the major slave trading regions of West Africa, where most of the slave trade was conducted.

“From the moment Africans were captured in the interior and coastlands of West Africa, to the time there were sold as slaves in the Caribbean and the new colonies of North America, black slaves acted as aggressively as possible, to maintain their African heritage and seek freedom. There were never willing victims. They resisted, survived and escaped.” And their efforts laid the first tracks of the Underground Railroad.

A Tale of Two Continents

“This is the story of a proud African people. It is a story that spans the Atlantic, linking forever the peoples of Africa and America. It is a story of places, North and South. It is a story of secrets, involving routes and language, codes and music. It is, in the end, a story of triumph and freedom, bought at great price, by individuals, cultures, and countries.”

Were Slaves Selected Randomly?

Historical documents provide proof that many plantation owners desired Africans skilled in areas that they lacked knowledge in, specifically, the harvesting of rice, sugar, and indigo, and slave traders sought out these particular Africans as slaves.

Slavery, an Economically Profitable Institution

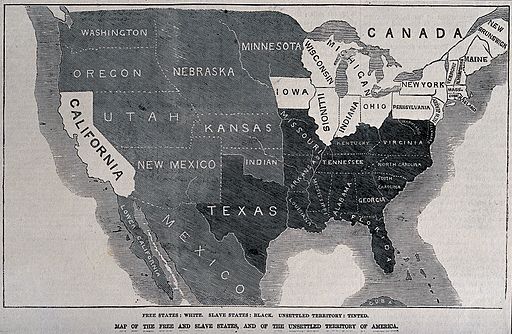

As early as 1619, indentured servants, both white and black, had arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. In 1641, over twenty years later, the Massachusetts colony wrote laws that authorized slavery, and the status of blacks changed. While white indentured servants were, eventually, allowed to acquire their freedom and rejoin society as equals, black indentured servants became slaves, with little hope of freedom. “This created the first distinction of servitude based on race in America.”

By 1775, all thirteen colonies legally recognized this “economically profitable institution” in direct contradiction to the principle of freedom on which the country was founded. This decision would have dire unexpected consequences in the future history of America. In The Underground Railroad, Lucia Raatma wrote:

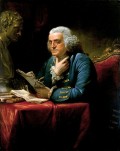

When the country’s founders wrote the U.S. Constitution in

1787, they struggled with the idea of slavery. Benjamin Franklin

was president of an abolitionist society that had been formed in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1775. Wealthy landowners

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, however, both owned

slaves.

“Many slaveholders dealt with the contradiction of ‘I believe in freedom’ but I have slaves, by their belief that they were providing security for people who could not do so for themselves.”

-Professor Spencer Crew, George Mason University, Virginia

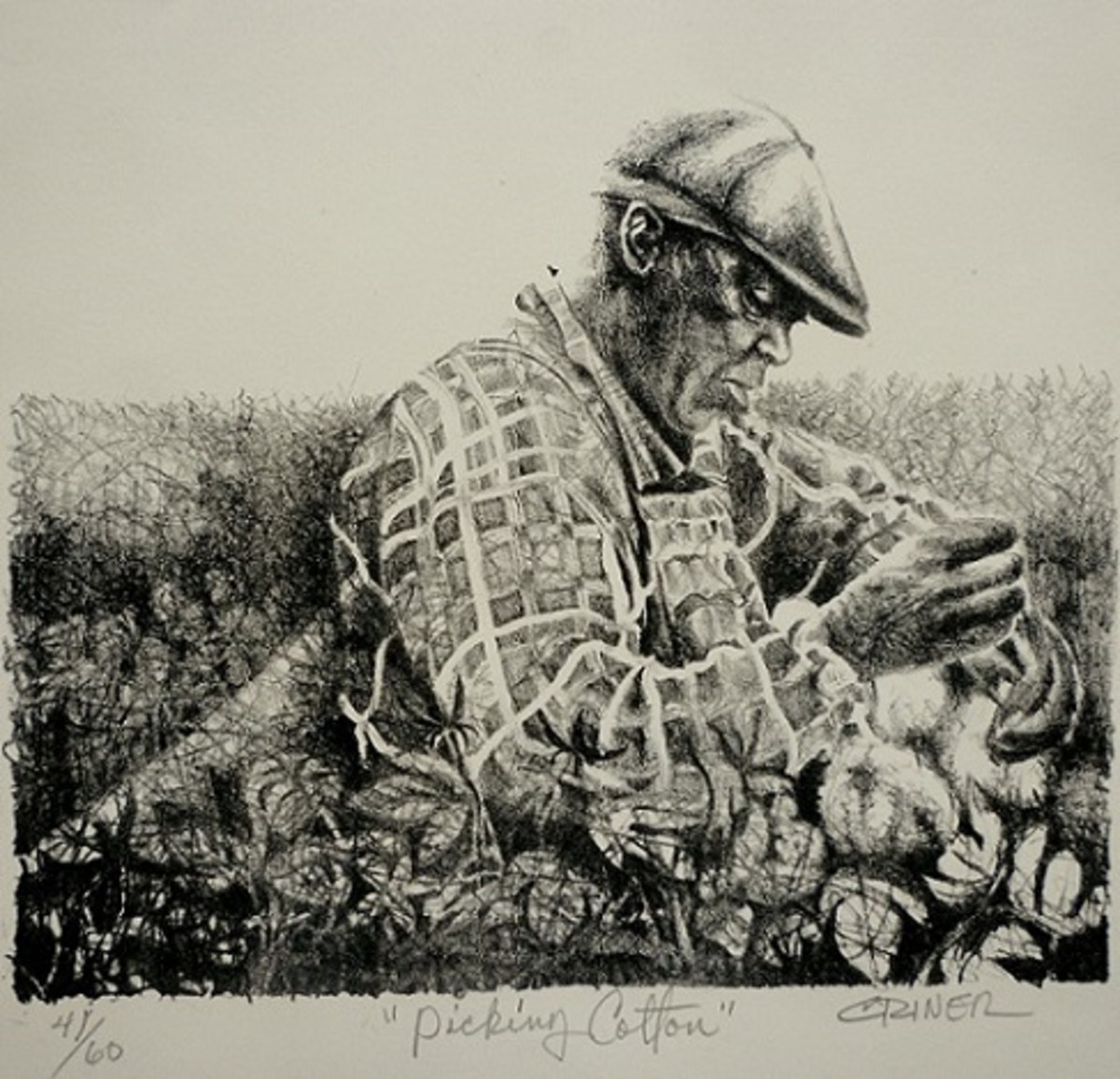

By the early nineteenth century the South’s economy depended on slaves to work in the plantation fields of cotton and tobacco, from 10 to 18 hours a day, in hot and humid weather, with no pay and substandard diets.

When the cotton gin enabled Southerners to become the principle supplier of raw cotton for Northern and European textile factories, slave labor ensured greater production and profit.

“By 1860, the dollar value of slaves—there were about four million—was greater than the dollar value of all of America’s banks, all of America’s railroads, all of America’s manufacturing combined.”

- Professor James Horton, George Washington University, Washington D.C.

And all benefited, except the slave.

A Network Built Out of Necessity

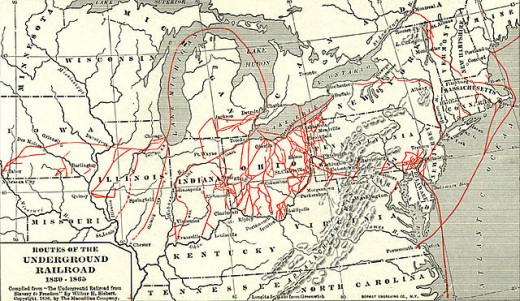

The Underground Railroad was not, literally, a railroad and it was not underground. Instead, it was an informal network of people and safe places that enabled fugitive slaves to move in secrecy, from bondage in the South, to freedom in the North, or many times, as far as Canada.

The system was most active in the 20 to 30 years leading up to the American Civil War (1861-1865). By this time, the slave trade had endured for more than two hundred years.

Where Did the Name Originate?

“Legend has it, it was a slave catcher who gave the Underground Railroad its name when the runaway he was chasing seemed to just disappear, as though the earth swallowed him up.” And the name stuck.

But there is no definitive explanation of how the term materialized. This and several different stories told by slave owners or slave hunters, to explain the disappearance of escaped slaves, contributed to its origin and, later, widespread use.

Building the Railroad, One Track at a Time

Many slaves who escaped knew where to go and how to get there. Why? Most free blacks who were part of the network were literate, so they were capable of passing on essential facts that were beneficial to future runaways, such as landmarks and geography, places to avoid, obscure trails, mileage and locations of safehouses, where food and rest were waiting. Although most early escape attempts were individual efforts, the tactics and routes that were used contributed, later, to a more organized system.

A World of Secret Codes and Terms

Naturally, every attempt to escape had to be kept undercover and not spoken of, therefore, it was absolutely essential to develop a “secret code of words and terms to describe the participants and safe places.”

There were people who guided runaways from one place to another. They were called conductors. Locations where slaves would be safe were called stations or safehouses. The average distance between stations was 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 kilometers). The farther north a runaway slave traveled, the closer together the stations became. People who hid fugitive slaves were called stationmasters. Runaways who were traveling with a conductor or staying with a stationmaster were known as cargo or freight.

The busiest parts of the railroad were near the regions that bordered slave states, which made the Ohio River the center of activity. It was called the River Jordan. Canada was a “safe haven” where slavery was illegal, and a fugitive’s ultimate destination. It was called “the promised land.”

The routes between stations were called lines. Two main lines carried most of the freight. One line crossed over into Canada at Niagara Falls, NY. The other, the Mason-Dixon Line, ran along the boundary between free and slave states, and put Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on “the front line of the great struggle over slavery.” Unfortunately, because slave hunters kept in close proximity to border towns, fugitives sometimes got caught “on freedom’s door.”

A Conductor Called Moses

One of the best known Underground Railroad conductors was Harriet Tubman, who was nicknamed “Moses,” after the prophet in the Bible who led the Hebrew people out of slavery in Egypt. In 10 years, she made about 19 trips back to the South and led more than 300 people, including her own family to freedom.

Stations and Safehouses

Many slaves who escaped stayed in personal residences. Often, a stationmaster used a lit lantern as a signal that their home was safe.

Oakdale was the name of a home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and the first Underground Railroad stop north of Delaware. What made it unique was a secret square room located between a walk-in fireplace and a carriage house wall. It housed runaway slaves.

White Horse Farm, located in Schuylkill Township, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, was a safehouse with an illustrious owner, Elijah F. Pennypacker, a member of the Pennsylvania State Legislature.

Churches were also “safe places” for fugitives, particularly, AME or African Methodist Episcopal churches. The Bethel AME Church in Indianapolis, Indiana, and the St. James AME Church in Ithaca, NY were included on the list of important Underground Railroad stations.

Throughout the United States, there were dozens of other stops on the railroad, but they were not always along escape routes. In those situations, runaways improvised. They built temporary shelters or used barns or empty sheds as places to sleep for the night. Frequently, graveyards were used as hiding places, because of their locations near churches, or their proximity to rivers or the outskirts of town.

Fugitive slaves may have spent days hiding in swamps, “knowing that to be spotted was to be caught,” as they traveled with only the North Star to guide them, hiding by day and running by night.

A Journey of Uncertainty and Fear

Overall, the Underground Railroad stretched for thousands of miles. From Kentucky and Virginia the lines spread across Ohio and Indiana. From Maryland, the lines crossed Pennsylvania into New York and New England. This meant that escaped slaves traveled by any means possible: wagon, horse, boat and, later, train. But the main mode of transportation was on foot, walking for hundreds of miles. It was a tumultuous endeavor, which resulted in severe punishment, if unsuccessful.

The majority of escapees were healthy men, but also included among them were females, and both the young and old, alike, from many different states. Although women and children had a harder time, older people could not manage the miles of walking and other physical challenges.

“Of all the reasons to run—the beatings, the hard labor, the starvation diet—none compared to the breaking apart of family.” As a result, some slaves fled because they knew they were about to be sold, or to become the property of a new owner.

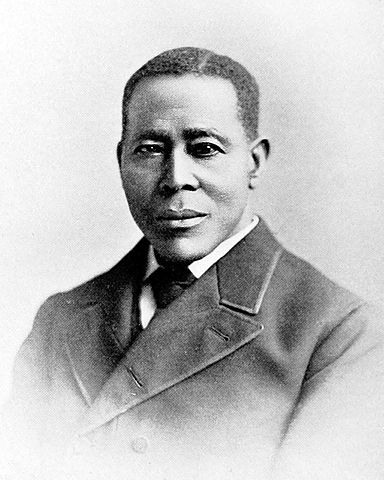

William Still, an Unknown Hero

William Still was one of the most important, but lesser known heroes of the abolitionist movement. Once designated the “father of the Underground Railroad” by The New York Times, by the late 1840s, Still had become the chief conductor in Philadelphia, one of the railroad’s central stations and busiest branches. He also used his home as a frequent stopover for fugitives and helped smuggle, on average, 60 escaped slaves a month, across the U.S. border to Canada.

“William Still didn’t invent the Underground Railroad, but he ran, arguably, one of the most important or busiest single Underground Railroad operations in the country.”

-Fergus Bordewich, Historian, Writer, Editor

Still was born a free man, and was the last of eighteen children. Prior to his birth, his mother, Sidney, escaped to freedom on her second attempt, along with her two young daughters. But she left her two sons behind, a decision she anguished over for the rest of her life.

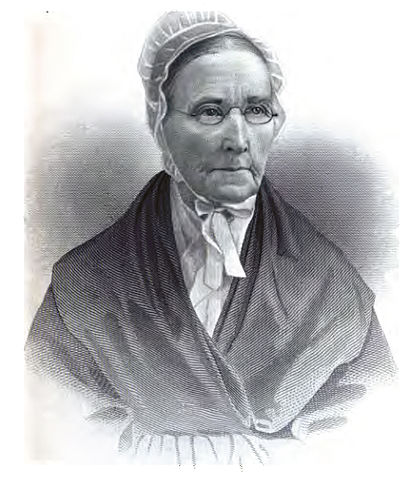

The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society

William Still joined the Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia and, eventually, became its secretary. (Lucretia Mott, a Quaker who worked for abolition, social reform and women’s rights, founded the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society along with her husband.) During his time of service, unbeknownst to him, in Alabama, a man named Peter Freedman had finally raised the $5,000 needed to purchase his freedom, after forty years in slavery. At the age of 50, Peter traveled 1600 miles from Alabama, where he and his older brother, now deceased, had toiled as slaves, “searching for any scrap of information about his family.” Finally, he arrived at the office of the Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. When William asked him if he knew the names of his parents, the stranger replied that his father’s name was Levin and his mother’s name was Sidney. At that moment, William Still realized that he was related to Peter.

“My dear brother who I had never before seen was before me. My feelings were unutterable.”

“Once William had his experience with Peter, he realized that families who were separated in slavery had no place to go to find one another, to find their relatives.”

-Gloria Still, Still Family Historian

From that moment on, Still was even more determined to reunite families separated by slavery. So, at great risk and with the knowledge that secrecy was essential for the safety of all, Still kept secret notes that detailed the fugitives’ stories—where they had come from, how they had escaped, and the families they left behind.

“It was an incredible risk to maintain these records about people he was helping to escape because it condemned both of them.”

-Rosemary Sadlier, President, Ontario Black History Society

After 14 years of service, when the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fr. Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, two months later, William Still resigned his position in the Anti-Slavery Society. During his time as secretary, he helped more than 800 fugitives on their journeys to freedom.

His book, documenting the names and details of escaped slaves, was later published in 1872, entitled, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, Etc. Narrating the Hardships, Hair-Breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom.

He died at the age of 81 and, by then, his book was recognized as “the most authentic account of the brightest moments in one of America’s darkest chapters.”

A Mass Movement to Abolish Slavery

The Quakers were the first organized group in the United States to oppose slavery, because it violated their Christian beliefs. Their strong opposition to slavery combined with an abolitionist movement in the North, and a large free black population, collectively, produced “the human synergy” that was needed to operate the Underground Railroad efficiently.

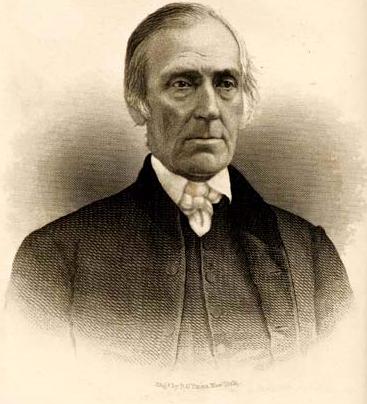

Grand Central Station

Two Quakers, who were very active in the Underground Railroad in Ohio and Indiana, were Levi Coffin and his wife, Catherine White Coffin. Their home in Newport, Indiana, was known as Grand Central Station. During the years they lived in Newport, Levi and Catherine helped about 2,000 slaves reach freedom.

Other Famous Abolitionists

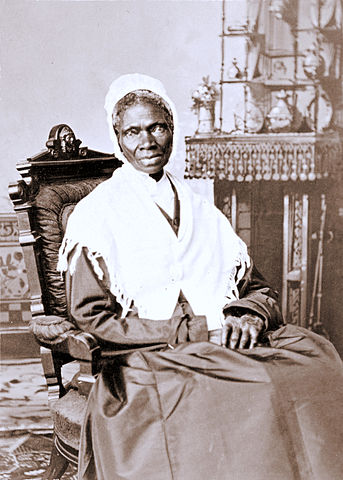

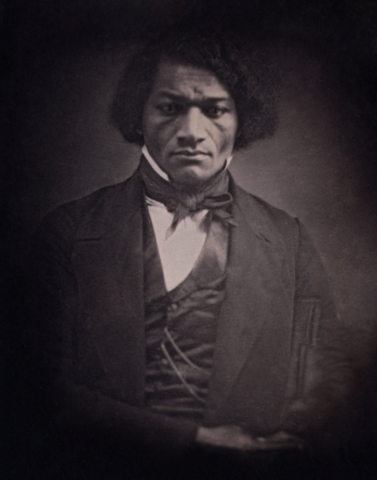

Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass are included among the list of well-known abolitionists. Both were slaves.

Sojourner Truth, a name she gave herself, was born a slave in New York, but she later escaped with her infant daughter. She was a proclaimed Christian who believed that “God had called her to preach against injustice.”

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland. He escaped to Canada and, subsequently, became a leader in the abolitionist movement, as well as a talented writer and public speaker.

Douglass wrote several autobiographies about the Underground Railroad, as well as his experiences as a slave. Among them are: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and My Bondage and My Freedom.

A Federal Law Passed to Appease the South

In the fall of 1850, in an effort to quell the frustrations of Southern slave owners and shut down the Underground Railroad, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act. It said that every state and territory in the United States was required to return fugitive slaves or escaped African Americans to their owners or their owners’ agents, and these agents had the right to seek them out anywhere in the continental United States.

It made assisting or hiding slaves a federal crime, punishable by jail or fine, as much as $500 (equal to approximately $10,000 today). Therefore, slave hunters could come to the North and force slaves back to their owners. This Act meant that many people who had successfully escaped slavery, established communities, and built new lives were no longer safe; no one was.

“It means there’s no safe haven left for fugitive slaves no matter how far they’ve run or how long ago.”

-Professor Karolyn Smardz Frost, York University, Toronto, Canada

Therefore, in order to hold on to their freedom, hundreds, possibly thousands, whole congregations of black churches and, even entire neighborhoods, picked up and, abruptly, immigrated to Canada.

The Compromise of 1850

In 1848, the United States acquired a great deal of land in the West, and as part of the compromise, California entered the Union as a free state. The territories of Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico were given the right to allow slavery, if they chose to.

Another part of the compromise was the second Fugitive Slave Act, which also passed in 1850, and was even more powerful than the first. It stated that any official who did not assist and return a runaway slave could be jailed or fined $1000 (equal to approximately $20,000 today).

A War on the Horizon

The preexisting turmoil between the North and South was fueled by these efforts to shut down the Underground Railroad, and eliminate any hope of freedom for slaves, from “the shackles of bondage.”

Whereas Northerners were frustrated by slave hunters who invaded their homes, looking for runaway slaves, Southerners were agitated by abolitionists who helped their slaves escape. This long-enduring battle over slavery would intensify and, eventually, erupt into an all-out war between the North and South.

Northern Boundary Lines Redrawn

In the end, the Fugitive Slave Acts that were intended to shut down the railroad had the exact opposite effect. Because the boundary lines had been redrawn for what north meant, the Underground Railroad became even longer. The railroad’s last stop was no longer one of the northern states. It now extended all the way into Canada, where under British law, slavery had been illegal since 1833.

This story continues in Part II. Thank you for reading this hub. Enjoyed the article? Have any questions or concerns? Leave a comment below or contact me anytime. I look forward to hearing from you.

References

Books

Raatma, Lucia. The Underground Railroad. New York: Children's Press, 2012.

Tobin, Jacqueline L., and Dobard, Raymond G. Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts' and the Underground Railroad. New York: Doubleday, 1999.

DVD

Underground Railroad: The William Still Story, 2012.