The Anthropic Principle for Dummies Like Me

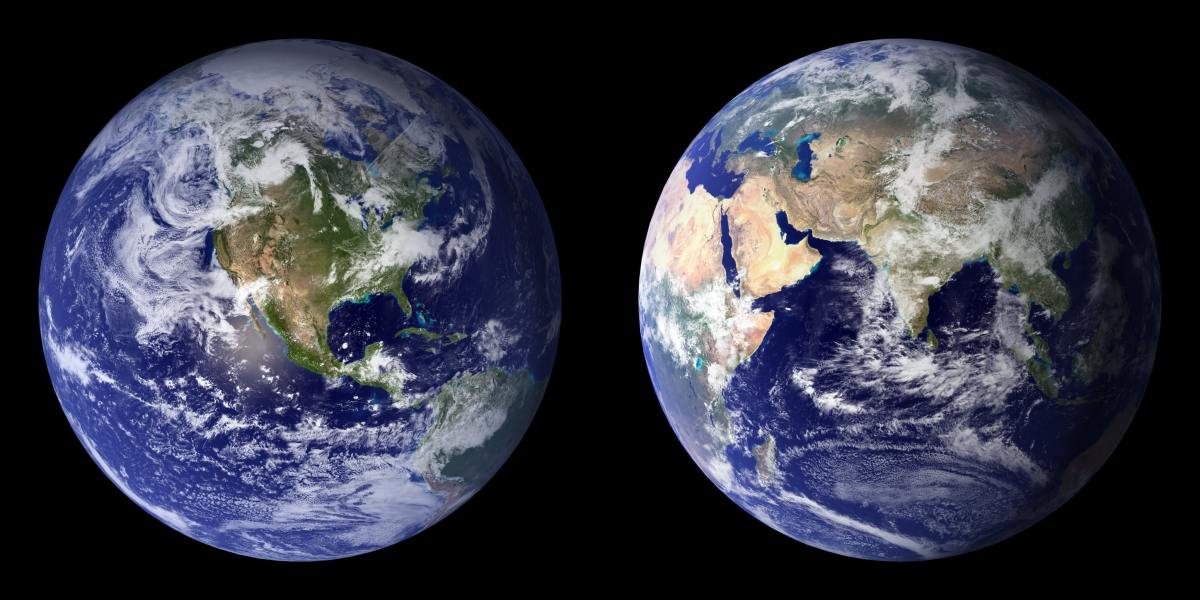

Goldilocks zone

You may have thought about how seemingly unlikely earth is to arise on this particular planet. If not, here's some food for thought: our planet, the earth, is in exactly that "Goldilocks zone", as astrophysicists call it, where life is suitable - not too close to the sun, like Mercury, where all organic life would simply bake away, and not too far away, where the world would be ice. Liquid water exists right here on earth, and as far as we know, liquid water is a necessary component for life to originate and evolve.

However, upon just a little bit of further examination, you can think about how there are seven other planets in the solar system, for eight total (sorry Pluto; please send all hate mail to Neil Degrasse Tyson). But what about the universe itself? Is it "fine tuned" for life? If so, how fortunate for us to exist! Is there a rational explanation for this besides evoking the supernatural? There is, and it's my goal to share it with you in plain language here. As always, if this does nothing more than to help you go to sleep at night sooner than you otherwise would, I will feel like I've done my job. If it opens a few new exploratory doors for your mind, even better.

The fine structure constant and other "lucky" numbers

In physics, the "fine structure constant" governs the strength of the bond between the electron and the proton. If this number wasn't exactly what it is, or very, very close, stars would not be able to sustain the nuclear reactions by which elements heavier than hydrogen or helium are created. In other words, we humans wouldn't be here, and neither would any life that we know of.

If the universe was 10% as old as it is now, stars wouldn't have had time to explode into supernovas, thus creating the elements by which we're made. If the universe was 10 times older, stars like our sun would have burned out (for the most part), leaving only white and brown dwarves, and life as we know it wouldn't have evolved, either.

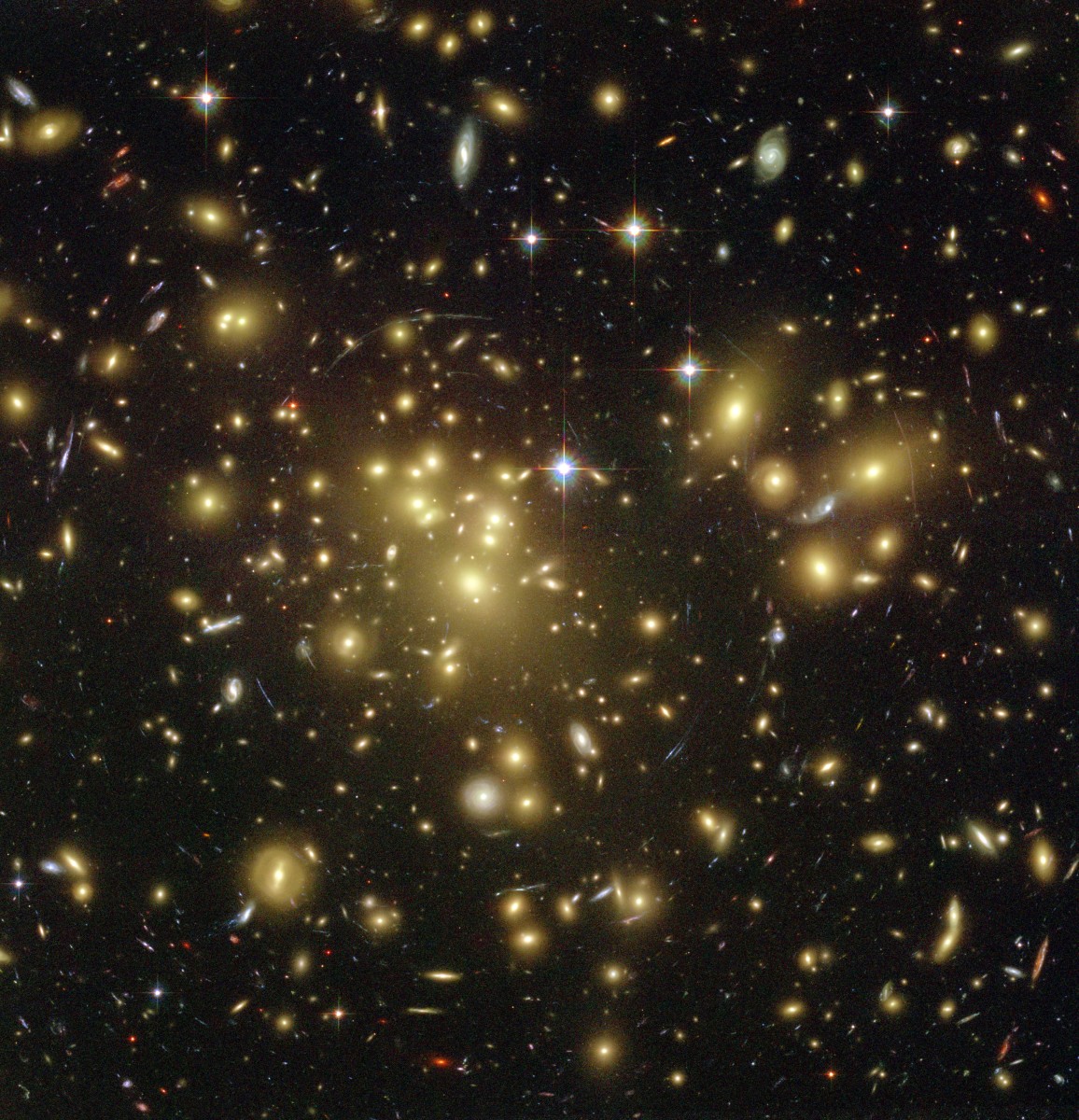

If the strength of any of the fundamental forces was just a hair off, we wouldn't exist! Imagine if the electromagnetic force was a bit stronger, say 20% stronger. Molecules wouldn't be able to form. If the cosmological constant (or "dark energy") was just a tiny bit stronger, galaxies wouldn't form in the first place (and without galaxies, presumably, we wouldn't have our solar system, either, or our sun, or the earth). On the other hand, if lambda (the cosmological constant) wasn't as strong, gravity would overwhelm the early universe, and black holes would dominate everything. Again, no galaxies, no stars, and no us. If the universe was made of different stuff, we wouldn't be here.

Oh hey, quick question:

What gives?!?

This is my thinking face

Answer #1: the anthropic principle

The anthropic principle gives us our first answer to the question: why is everything so fortunately the way it is? This answer is deceptively simple: because we wouldn't be here otherwise to even make the observation as to how fortunate we are to be here otherwise! To elaborate, we think that this universe (or solar system, or planet, or whatever) is something special by the very definition that we're here to make the observation that we're something special.

You can use biological evolution to underscore this observation even further. Of all the species known to exist on planet earth, more than 99% are currently extinct. Our species (the human one) is one of the very, very lucky ones indeed, the less than one percent that managed to survive! Imagine the odds that you are here reading this, given that virtually all other species are now extinct.

Imagine further, many, many humans were killed before they had the opportunity to reproduce. The average life expectancy during human prehistory was considerably shorter than it is today, and that's because so many people simply died in infancy. How lucky that you're not one of those infants who died before physical maturity, or one of those countless millions of cavemen who were eaten by a tiger, or who died of dysentery.

Even further still, virtually every human being that has ever lived is currently dead. How fortunate that you happen to be alive at this very moment in order to be able to read this wonderful, insightful article by yours truly!

How fortunate, indeed, that you are literate, and that the language you are reading right now is English, and that you happen to have stumbled upon this very Hub. What are the odds?

Vote

How many universes are there?

Answer #2: multiverse theory

The second answer physics offers to this conundrum is perhaps a bit more satisfying to our minds. The multiverse theory suggests that our universe is but one of many universes. How many? Perhaps infinitely many, or perhaps finitely many, but however many it is, it's certainly considerably more likely to come up with a universe in which all of the laws of physics are just so when you have many, many more opportunities for those constants to arise. The mutiverse theory suggests that in other universes, perhaps the fine structure constant and the various strengths of the forces of nature aren't the same as they are here in our universe.

Assuming that the number of other universes (think of each universe as an enormous bubble, one that will never, ever cross over any other universes) is infinite, that means that somewhere, out in another bubble, is a universe where the gravitational force is far, far stronger, and there's nothing but a supermassive black hole encompassing all of the mass. In another "island universe", there's twice the electromagnetic force, so atoms never form into molecules, and we don't exist. In still another universe, lambda is so high that the galaxies never formed, and the universe is nothing but a sparse collection of subatomic particles, ever accelerating and expanding.

And still weirder: there's another you out there, identical in every single way, down to the atom. And there's another you that is identical down to the atom except for having brown eyes instead of green eyes, or pattern baldness, or six fingers on one of your hands. Everything that can happen does happen, because the number of universes isn't just high- it's infinite.

Galaxies in our universe

The state of the theory

Is this the way things are? We have absolutely no idea right now, but there are, believe it or not, some ways to test whether the multiverse concept is real. Unfortunately, the theory isn't currently falsifiable - we could uncover potential evidence for the existence of these other universes, but we can't currently come up with a way to disprove them. After all, if these universes never encountered our own universe (it's important to note that several different versions of multiverse theories state that they have, in fact, crashed into one another, and one of these such crashes may be responsible for the Big Bang itself!), so there's no way we can know for sure if they exist or not. As such, the multiverse theory, while perhaps a useful mathematical construct, remains speculative and not within the current predictive canon. Nevertheless, it's important to think a bit ahead of the experimental curve, so to speak, to come up with lots of diverse ideas that may be one day testable. After all, today's science fiction often becomes tomorrow's science fact!