- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Time for Change: Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Time for Change: Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Born on November 12, 1815, Elizabeth was the eighth of eleven children born to Judge Daniel Cady and his wife Margaret, though tragically seven of her siblings died young. Because her parents were emotionally distraught over the deaths of their children, much of the child-rearing was left to Elizabeth’s oldest sister Tryphena and her husband, Edward Bayard, a legal clerk in her father’s office. Bayard spent a lot of time educating Elizabeth on law—and how it didn’t exactly favor women.

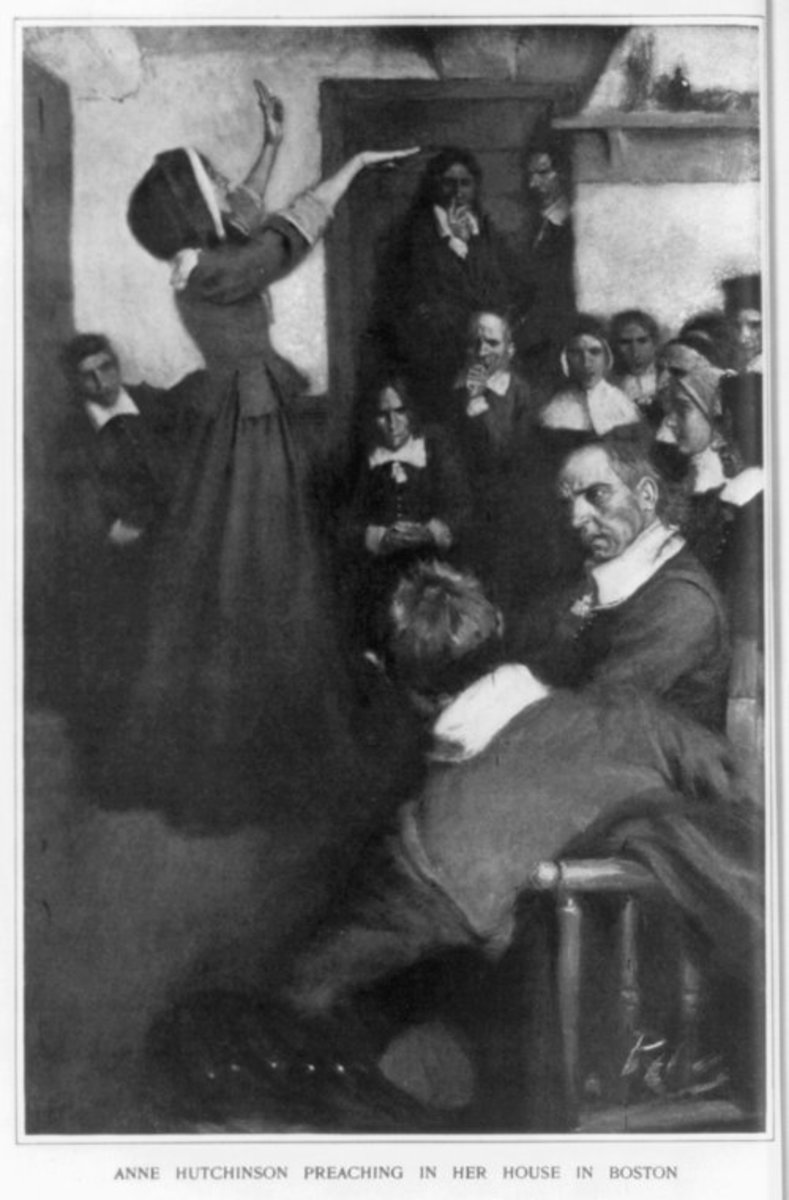

When Elizabeth was young, her older brother Eleazur died suddenly, and her parents were devastated. Elizabeth tried to comfort her father, but she was shattered when Judge Cady lamented, "Oh, my daughter, I wish you were a boy!" In tears, Elizabeth went to her neighbor, Reverend Simon Hosack. Hosack was angered by Judge Cady’s words and then proceeded to give her a classical education that would rival any boy of her age, something that was highly unusual for girls at that time. Later, she graduated from Emma Willard’s Academy, but she was disappointed that she could not go on to attend college.

As a young woman, Elizabeth became highly active in the abolitionist and temperance movements. It was during her work with the movements that she met young journalist and future attorney Henry Stanton. They married in 1840 after Elizabeth made the minister omit “promise to obey” from the wedding vows ("I obstinately refused to obey one with whom I supposed I was entering into an equal relation,” she said), and she kept her last name in addition to Henry’s. They settled in Boston, Massachusetts and had seven children.

In 1840, Elizabeth and Henry traveled to England to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention, where she hoped to hear the Quaker minister, abolitionist leader and future friend Lucretia Mott speak. To Elizabeth’s shock, Lucretia was not allowed to give her speech.

Why?

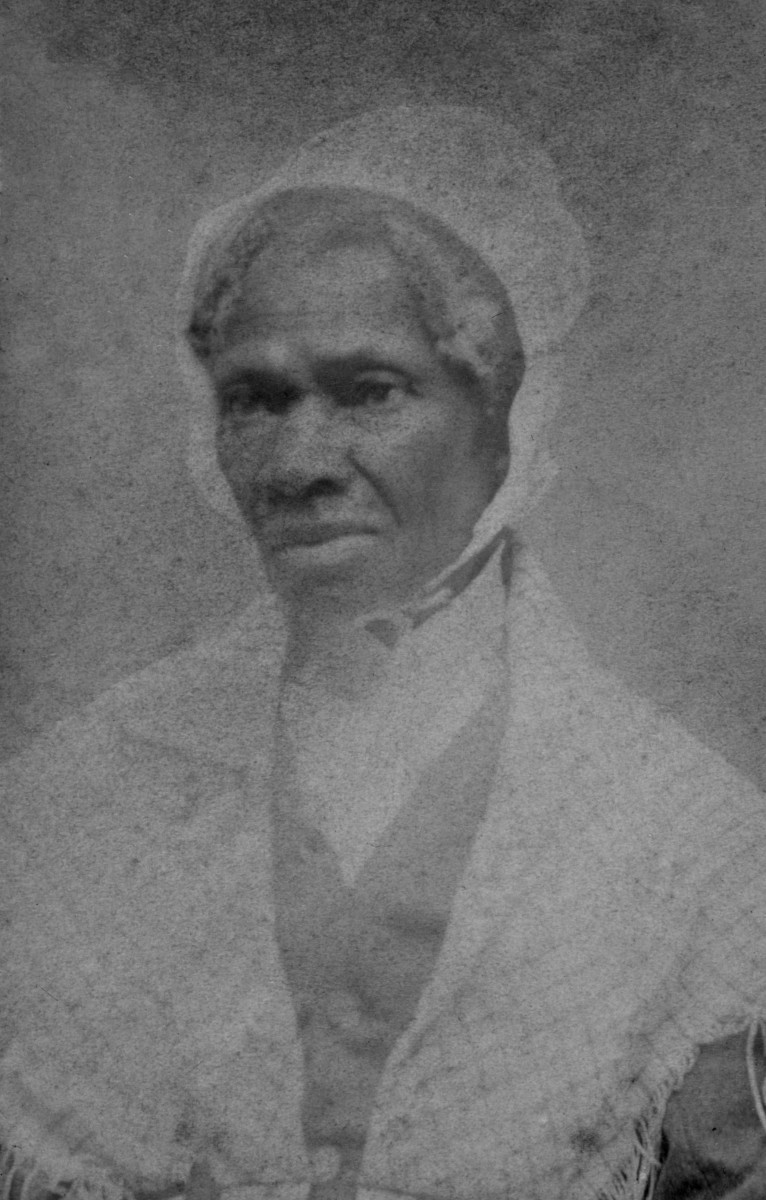

Because she was a woman. Women weren’t allowed to speak at the convention, though many of them had worked hard to end slavery in their home countries. Years later, Elizabeth recalled the conversation she had with Lucretia afterwards: “As Mrs. Mott and I walked home arm in arm … we resolved to hold a convention … and form a society to advocate the rights of women.”

At first, Elizabeth loved being a housewife, with all the cooking and cleaning and minding the children, and often wondered why so many other women hated it … and then they moved to Seneca Falls, New York, and Elizabeth learned a shocking truth: she loved housework because she wasn’t really doing anything. Most of the cooking, cleaning and childcare was done by the family servants, not by her. When they moved to Seneca Falls, they left behind their old servants and hired new ones that had very little training, forcing Elizabeth to do nearly all the work—work that was complicated by her hyperactive and often sick children getting underfoot. Being constantly busy with no reward or recognition for her work made Elizabeth very unhappy. “The novelty of housekeeping passed away,” she admitted.

To escape the frustration, Elizabeth often visited with Lucretia Mott, to whom she vented her feelings with “vehemence and indignation.” During this time Elizabeth and Lucretia often discussed how poorly women were treated, how laws favored men and husbands over women and wives (for example, a husband had the legal right to beat his wife, and if she divorced him he kept her property and their children—even if he was abusing them as well—and she never would receive alimony, or if a woman was forced to work to support her family she was legally forced to hand over her earnings to her husband and had zero control over what he did with it.) Many women felt the way Elizabeth and Lucretia did, filled with anger and resentment at a society that still treated them as inferior humans in comparison to men. Women had no legal rights, no higher education, and no way to support or protect themselves as long as these archaic laws were still in place. The only way to get these laws changed was to give women the legal right to vote, something that Elizabeth and fellow abolitionist Susan B. Anthony would come shortly after black men were given the right to vote, but it had never happened. Something had to be done about that.

Deciding that enough was enough, Elizabeth and Lucretia decided it was time for a change. They placed an advertisement in the local newspaper announcing that there would be a two-day meeting to discuss the rights of women in America (later called the Seneca Falls Convention), to be held at a nearby Methodist church. Together the women drafted a Declaration of Sentiments, modeling it on the Declaration of Independence, outlining the inequalities women suffered and declaring that a change must be made to free them. On July 18, 1848, the roads to the church were clogged with wagons and carriages, filled with people who wanted to take part in the meeting. Elizabeth and Lucretia were stunned to see forty men arrive as well—they had originally intended that the meeting be women-only, but they decided to let the men in. Somewhat oddly, Elizabeth and Lucretia asked Lucretia’s husband James to preside over the gathering.

Once the meeting was called to order, Elizabeth stood, speaking for the first time ever in public. Though nervousness prevented her from speaking very loudly, Elizabeth nevertheless stated that women have been denied their rights for far too long, and that the laws that kept them oppressed had to be changed … and she knew exactly which law had to change first: women had to be given the legal right to vote.

This wasn’t something Elizabeth had discussed earlier, and Lucretia was horrified, gasping, “Oh, Lizzie! If thou demands that, thou will make us ridiculous! We must go slowly.” Not only were the Motts aghast, but Elizabeth’s own husband Henry (who was against women getting the right to vote) was so embarrassed by the tumult she caused that he left town. Word of her statement reached her father, who rushed to her house to see if she had gone insane, then threatened to disinherit her if she continued to talk about giving women the right to vote (although Elizabeth might not have cared too much about that—anything she inherited would be placed under the control of her husband.)

Things got worse; the convention at Seneca Falls attracted national newspaper coverage, though it mostly ridiculed everything about it, including Elizabeth. The fallout was so bad that most of the women who had sign Elizabeth and Lucretia’s Declaration retracted their names. Two weeks later Elizabeth attended another women’s rights convention in Rochester, NY, but she thoroughly embarrassed herself when she refused to support a motion that a woman preside over the meeting. Mortified, Elizabeth later wrote to a friend, “My only excuse is that woman has been so little accustomed to act in a public capacity that she does not always know what is due.”

Instead of retreating and hoping everything would blow over, Elizabeth began to press even harder for women’s rights. She was delighted when Amelia Jenkins Bloomer (who had attended the Seneca Falls Convention) invented “bloomers,” a type of billow harem pant for women that kept their modesty but freed them from layers of skirts and petticoats. Elizabeth loved wearing them, but the backlash was horrendous; her friends refused to have anything to do with her as long as she wore bloomers. In the streets little boys would harass and make fun of her, and outraged men would screech that bloomers were blasphemous, going against Deuteronomy’s decree prohibiting cross-dressing.

Though no one knows exact how they met, Elizabeth and Susan B. Anthony became friends and remained so for over fifty years, even though their personalities were vastly different. For example, Elizabeth loved being a wife and mother, but Susan thought that marriage and childbearing was an act of betrayal to the cause “for a moment’spleasure to herself or her husband, she should thus increase her load of cares under which she already groans.” Elizabeth liked to stand up to people and loved to say things to shock a crowd (when expressing her frustration that black men had gotten the right to vote but both white and black women didn’t, she shocked her friend Frederick Douglass,) while Susan, though she did most of the public speaking, wasn’t as strong willed and often had serious doubts about her abilities.

Elizabeth and Susan communicated largely through letters, which apparently was a blessing for the Stanton children; later, Elizabeth’s daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch remarked that to see Susan B. Anthony standing on their doorstep “was not a matter for rejoicing.”

By now suffragism was in full swing and had been solidly divided into two factions, with moderate Lucy Stone and her followers on one side and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and many other more radical followers on the other.

Now leaders of the suffrage movement, Elizabeth (now president of the National Women’s Suffrage Association or NWSA) and Susan played to their strengths, with Susan, always a fiery orator, traveling and speaking at public events, and Elizabeth wielding her pen, crafting letters and impassioned speeches from her desk.

Seeing that it may be too difficult to get support for women’s rights in places like New York, Elizabeth and Susan would make regular “pilgrimages,” as Elizabeth called them, to Wyoming, where women had the legal right to vote for years (women played such a vital role in the creation of Wyoming that when it came time to ratify the state, the men refused to join the Union unless the women were permitted to vote as well.) Though people there might have been a little more supportive than in other states, Elizabeth and Susan were still met with detractors. “Neither one is handsome,” sniped the editor of the Cheyenne Leader.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

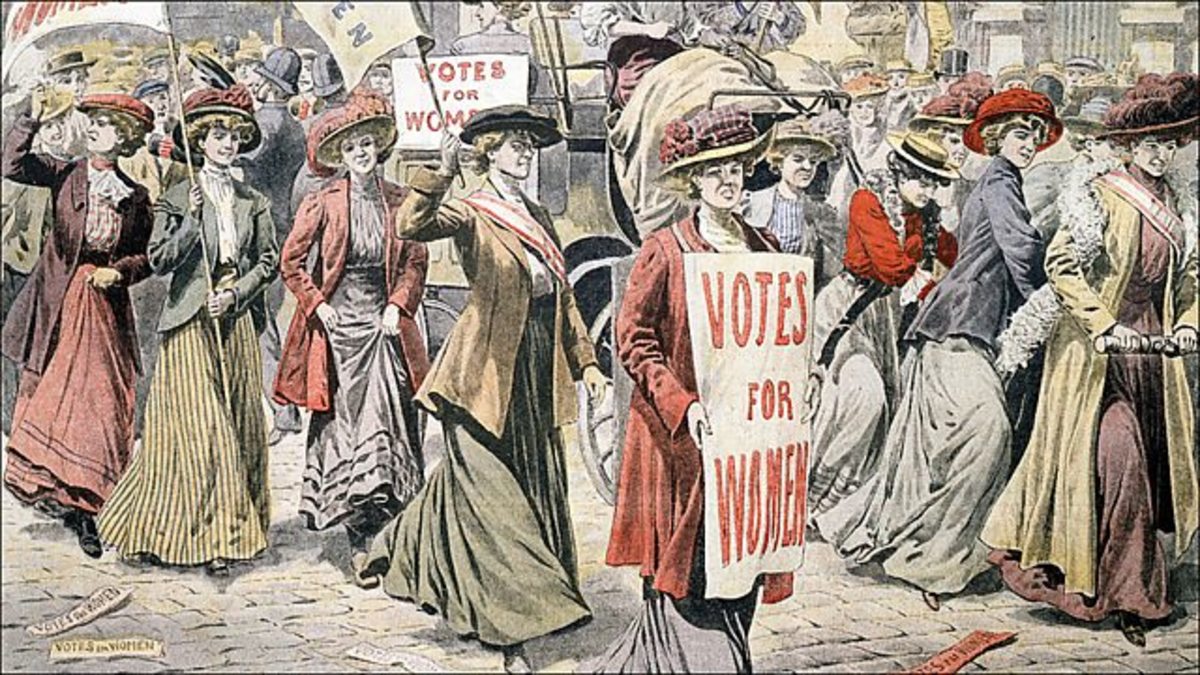

Harassment and criticism only seemed to strengthen Elizabeth, Susan and the other suffragettes’ resolve, and they continued to march, picket, distribute flyers, speak and write about women’s rights and the unfairness of their treatment. Elizabeth was bold enough to publicly defend Hester Vaughn, a rape victim who was facing a death sentence after her baby (the result of the rape) had frozen to death in her derelict hotel room. Elizabeth wanted stricter prosecution of rape, repeal of birth control laws, the acceptance of women into higher education, a change to divorce and property laws, and she wanted changes made to organize religion (much of women’s oppression was rooted in misogynistic religious teachings). Hoping to see these changes made, Elizabeth ran unsuccessfully for a congressional seat in 1866, and in 1872, Susan and fifteen other women were arrested in Rochester, NY for attempting to vote in a presidential election.

Though the suffragette movement continued on and was considered a legitimate and respectable cause, after so long it began to run out of steam, and with few notable changes being made (she did successfully get the Woman’s Property Bill passed in New York), and Elizabeth and Susan began to fear that they wouldn’t live to see women get the right to vote.

On January 189, 1892, Elizabeth, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone and Isabella Beecher Hooker stood before the United States House Committee on the Judiciary to speak about the suffrage movement. In her last public speaking engagement, Elizabeth said, “The strongest reason for giving woman all the opportunities for higher education, for the full development of her faculties, her forces of mind and body; for giving her the most enlarged freedom of thought and action; a complete emancipation from all forms of bondage, of custom, dependence, superstition; from all the crippling influences of fear—is the solitude and personal responsibility of her own individual life. The strongest reason why we ask for woman a voice in the government under which she lives; in the religion she is asked to believe; equality in social life, where she is the chief factor; a place in the trades and professions, where she may earn her bread, is because of her birthright to self-sovereignty; because, as an individual, she must rely on herself ...."

At a tribute given in her honor on her 80th birthday, Elizabeth quipped, “I fear you think the New Woman is going to wipe you off the planet, but be not afraid. All who have mothers, sisters, wives or sweethearts will be very well looked after.” Never one to miss an opportunity to shock people, Elizabeth then declared it was time to rewrite the Bible. In 1898, she did just that, writing The Woman’s Bible. The NWSA was shocked by its publication and censured her. This eventually led people to see Elizabeth as too controversial and to give Susan B. Anthony nearly all the credit for suffragism and its success.

On October 26, 1902, eighteen years before the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was passed, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died of heart failure in her home. Her daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch continued the fight for her.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton works cited:

America’s Women, by Gail Collins

“The State Where Women Voted Long Before the 19th Amendment,” http://www.history.com/news/the-state-where-women-voted-long-before-the-19th-amendment

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Cady_Stanton#Childhood_and_family_background

“Declaration of Sentiments,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_Sentiments

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton,” http://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/elizabeth-cady-stanton

“Seneca Falls Convention,” http://www.historynet.com/seneca-falls-convention

“Seneca Falls Convention,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Falls_Convention

Suffragettes Picketing Outside the White House, 1917