Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

What is the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment?

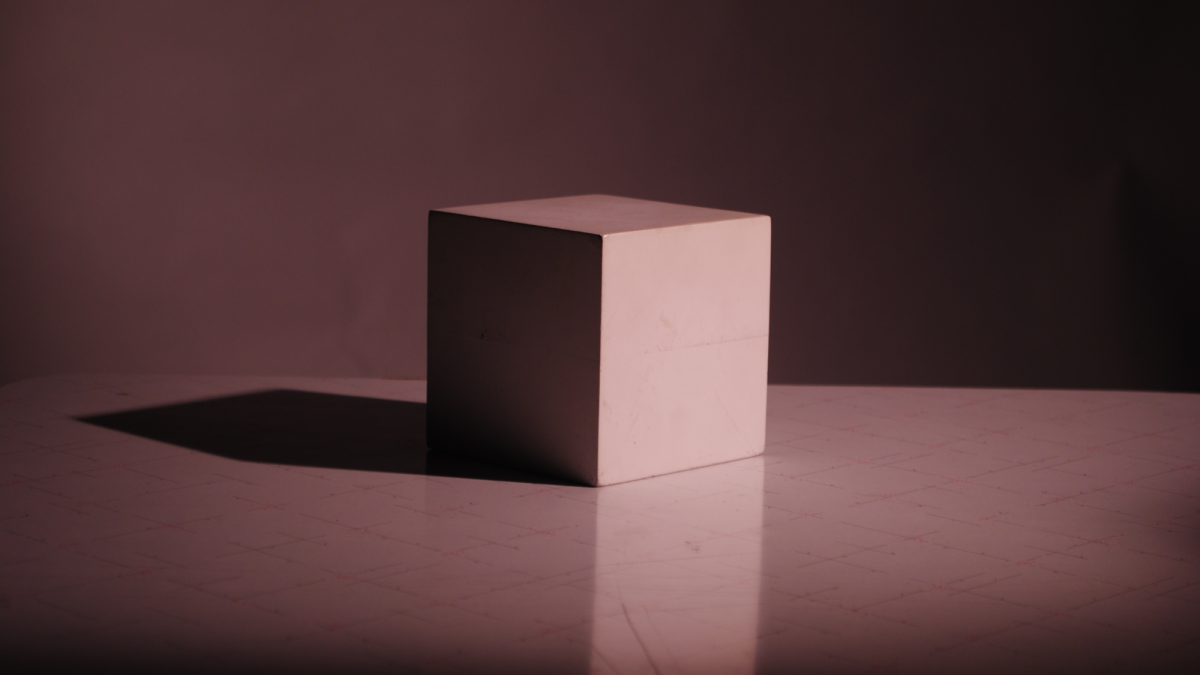

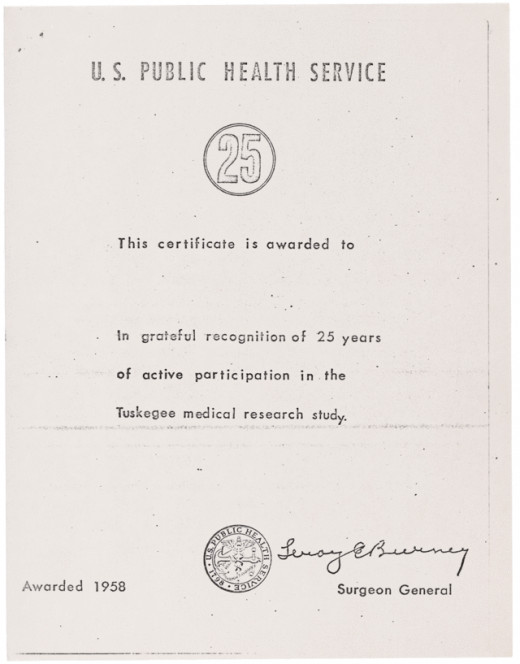

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was an experiment conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service between 1932 to 1972 in Macon County, Alabama. The study was meant to discover how syphilis affected blacks as opposed to whites.

600 African American men were chosen for this study. 399 of the men were in late stages of syphilis while 201 of the men were healthy. The syphilis they were studying was tertiary syphilis.

The men who volunteered for the experiment were given free medical care, free meals, and free burial insurance for participating.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was named after the Tuskegee Institute who helped in the experiments.

What is Tertiary Syphilis?

Tertiary syphilis occurs anywhere between three to fifteen years after an initial infection of syphilis. It is not infectious. Tertiary syphilis can turn into gummatous syphilis, neurosyphilis, and cardiovascular syphilis.

Gummatous syphilis occurs on average fifteen years after initial infection of syphilis. Someone who has gummatous syphilis will start to form soft, inflamed, tumor-like balls that vary in size. Gummatous syphilis can occur anywhere, but usually affects the skin, bone, and liver.

Neurosyphilis is an infection involving the central nervous system. Someone with neurosyphilis may have seizures, dementia, and their pupils may constrict when they focus on close objects but do not constrict in bright sunlight.

Cardiovascular syphilis can result in aneurysms.

Considering the facts, do you think it was wrong for the nurses and doctors to deny medicine to the volunteers?

Ethical Issues of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

One of the biggest ethical issues involving the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was the fact that the test subjects didn't know that they had volunteered for the study in question. The 'volunteers' of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment thought they were being treated for 'bad blood'. This was a local term for illnesses including syphilis, anemia, and fatigue.

To make matters worse, the study didn't need the volunteers alive. In fact, data from the experiment was to be collected from autopsies of the volunteers.

While the volunteers thought they were getting free medical care, doctors and nurses involved in the experiments purposefully gave the volunteers extremely small doses of treatment for syphilis. So small, it helped less than 5% of volunteers. Eventually, doctors and nurses gave them 'pink medicine' - a medicine that didn't help syphilis at all. Ultimately, the volunteers were left to degenerate by means of syphilis.

In the midst of the study, in the 1940s, it was discovered that penicillin was a cure for syphilis. Although this was known, the experimenters refused to give the volunteers any, denying them if they asked for any cure. Some volunteers even tried to join the U.S. Army and when refused because of their syphilis, the experimenters refused them to join the Army.

Regardless of what the volunteers needed to stay healthy, the 'doctors' always had the final say in their treatment. Countless times nurses knowingly denied and lied to their patients in order to protect the validity of the experiment. Even after the experiment was over, some nurses felt like they didn't do anything wrong.

Many nurses and doctors, some even African American, were promised mentions in the experiment papers and hoped to create a name for themselves.

More Ethically Questionable Experiments

Other Ethical Issues of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

While the experiment was being conducted, two laws were put into effect. One was the Henderson Act in 1943 and the other was the World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki in 1964.

The Henderson Act required testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases.

The World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki spoke for human rights in experiments and set ethical principles for human testing. In the World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent was required for experiments involving human beings.

While knowing that the Henderson Act and the World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki were in effect, the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment continued on.

Results of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment ended in 1972 after the experiment came to public light in an article written by Jean Heller in the Washington Star's July 25, 1972 issue.

At the end of the experiment, 28 men died of syphilis and 100 men had died for related complications. 40 of the men's wives were infected with syphilis and 19 of their children were born with congenital herpes.