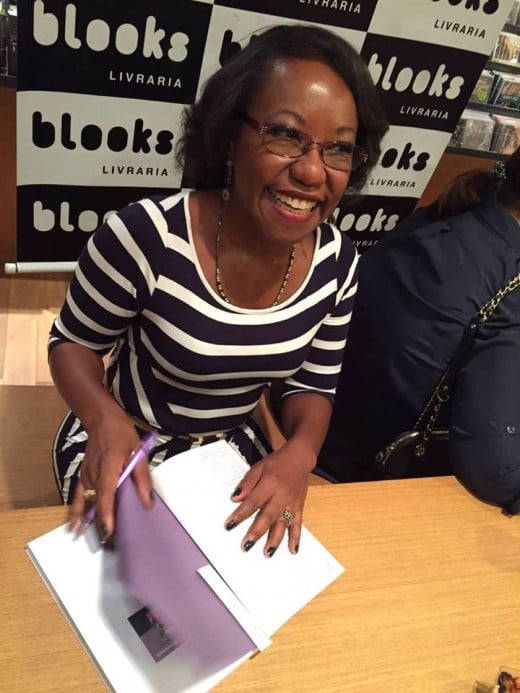

Vânia Penha-Lopes

Vânia Penha-Lopes is speaking up about racial and ethnic identity issues and colorism around the world.

A tenured professor at Bloomfield College in Bloomfield, NJ and an intellectual lecturer, Vânia is focused on speaking at colleges and conferences here in the U.S. and abroad to address the consequences of the African Diaspora.

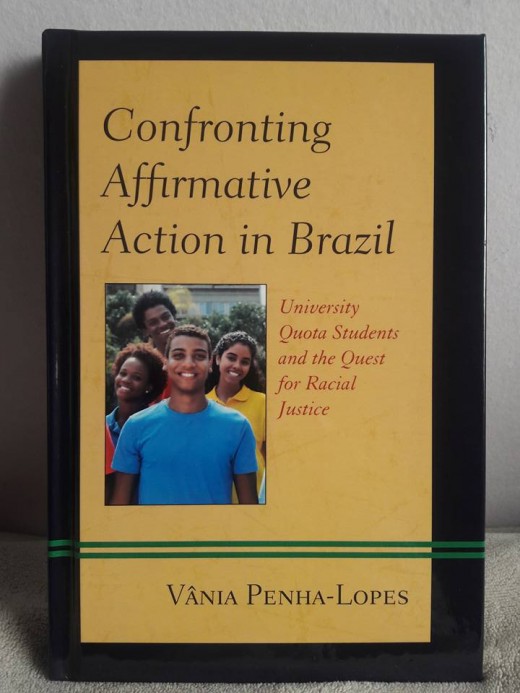

Vânia has authored two books, Confronting Affirmative Action in Brazil: University Quotas and The Quest for Racial Justice (2017) and Pioneiros: Cotistas na Universidade Brasileira (2013), as well as co-edited Religiosidade e Performance: Diálogos Contemporâneos (2015).

She serves as the co-chair of the Brazil Seminar at Columbia University (2008-present) and was a member of the executive committee of the Brazilian Studies Association-BRASA (2010-14).

A native of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Dr. Penha-Lopes graduated with honors from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro with a Bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences (1982). She is also a graduate of New York University, with a Master’s degree in Anthropology (1987) and a Ph.D. in Sociology (1999).

As a post-doctoral fellow at the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (2006-07), she did research on the first graduating class of Brazilian university quota students. She has received a number of awards, including the Carter G. Woodson Institute Predoctoral Fellowship in Afro-American and African Studies, from the University of Virginia (1996-98), and the Scholarship for Study Abroad from the Encyclopaedia Britannica do Brasil (1982), of which she was the youngest recipient.

With a particular interest in speaking on Comparative Race Relations, Racial & Ethnic Identity, and Colorism around the World, Dr. Penha-Lopes has lectured extensively on race and ethnicity, African American fatherhood, and racism in Brazil and has been interviewed for articles in Diverse Issues in Higher Education, O Estado de São Paulo, and The Washington Post. Her work has been cited in a number of books on race relations, in textbooks, and in peer-reviewed articles.

Dr. Penha-Lopes’ life experiences as an Afro-Brazilian and interest in the African Diaspora as a teacher make her a great personality for radio and TV interviews and panel discussions on the subject. In addition, her long career as a tenured professor is her passion for informing the public about the U.S., Brazilian, and Latina cultures that more connect us than we may be aware.

Q&A with Vânia Penha-Lopes

Q) Vânia, you are a tenured college professor at Bloomfield College in NJ. How long have you been a professor, what do you teach, and how did you get started as a professor?

A) After I got my master’s in anthropology and started a doctoral program in sociology at NYU, I began teaching college part-time in 1987. I also got teaching assistantships (TA) while in graduate school. At NYU, TA’s were fully responsible for their undergraduate courses, so I have been teaching ever since. My main focus has been on courses on the sociology of race and ethnicity and on family, and a number of specific topics within them, such as racial identity formation, African American families, African American fatherhood, masculinities, comparative race relations, and African American thought at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. I also teach social inequality and stratification, urban sociology, and introduction to sociology. Last year (2017), I started teaching social change, with a focus on the U.S. in the 1960's; I have enjoyed it immensely. Students get to see documentaries about the Civil Rights Movement, the youth counterculture, and the Vietnam War, and the rise of television as the main medium of mass communication. That course is now a staple of mine. This semester (Spring 2018), I am teaching a course on whiteness for the first time. I have created this course to focus on the roots and maintenance of the system of social stratification in the U.S. It is a challenging course because it requires students to get away from individual and essentialist explanations for the maintenance of prejudice and discrimination. It is a relevant course because it takes the focus away from “minorities” and moves it toward the roots of minority/majority status.

Q) Did you always want to teach after you finished your education, or was that something that became a natural progression?

A) As young as five years of age, I would answer to the question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” as “A scientist, an English teacher, and a writer.” I don’t know where my prescience came from, but I am indeed all three. As a sociologist and anthropologist, I am a social scientist; I am trained as a teacher of English as a foreign language; and I started writing poems when I was eight years old. At age 14, I decided to become an academic when I learned I could be paid to read and write. Writing is my passion; teaching is part and parcel of being a professor.

Q) Who was your biggest influence as a child growing up?

A) That is a tough question to answer, for I am fortunate to have had many strong, loving, and supportive influences in my life. My maternal grandfather, with whom we lived until I was eight, was the son a slave. I grew up knowing he had only a third-grade education, but he loved books, a love he passed on to my mother, who then built a library for us even before we were born; for example, I read all of Andersen’s tales as a little girl. My grandfather was and is my idol. He worked out diligently when that was not even in fashion, and I remember getting up early in the morning to work out with him. He was way ahead of his time by inculcating in his three daughters the necessity to work for pay. My mother is a retired social worker; she got a university degree at a time when most Black Brazilians were illiterate. My grandfather was also a very elegant man, with notoriously impeccable manners. He’s been gone for over 30 years, but I miss him to this day. My paternal grandmother taught herself to read by listening to her brother’s lessons; we’re talking about the 19th century, a time when Brazilian women were not commonly formally educated. She read the newspapers every day and was aware of current events throughout the world. Unfortunately, my maternal grandmother and paternal grandfather died before my parents ever met. My mother, who is 93, has a tremendous joie de vivre; she still goes to the gym regularly. She loves reading and is a very good writer. She taught us how to type when I was ten years old and was keen on our getting a great education. She enrolled my sister and me in English lessons when we were pre-teens; by the time I got to the U.S., I had won awards as the best student in all of the City of Rio de Janeiro at the school we went to. My mother told us early on that a woman must have her own career and salary so as to be independent. My father was very involved. He told us bedtime stories, read to us before we learned how to, taught us how to whistle. He also taught me to be sensitive to musicality and rhythm, and to pay attention to detail. My father taught himself how to play the harmonica and how to speak English when he was a teenager; he spoke so well that some thought he was from the U.S. when he came to visit when he was close to 60 years of age. He bought us books about science for kids and got involved in my school projects. For example, when I learned about the solar system, he built a device that would showcase each planet by pressing buttons that would light each in different colors. When I learned about the DNA molecule, he suggested we build a model of one. He would also take us on long walks and to the beach on Sundays. My father died over four years ago; I am so thankful for our time together. Both my parents worked for pay. During the day, we were cared for by our aunt, Tia Odete, who was a stickler for discipline and perfection. She was the one who checked on our homework, ironed our school uniforms, took us to school, fed us. She is a resilient 95-year- old who is very active in church and travels regularly.

Q) We often hear about the Diaspora as it relates to African Americans without

realizing the Diaspora was global. What has this meant for you as a teacher and how do you relate your own heritage in what you teach?

A) Most Americans, regardless of race, are unaware that only a minority of Africans came to the U.S. as slaves. The overwhelming majority went to Brazil, for a much longer time, and to a much larger area. That makes Brazil the country with the largest population of African descent outside of Africa. Brazilian mainstream culture has strong West African roots, in addition to the indigenous and the Portuguese. Unfortunately, Brazil is also the country where the highest numbers of Blacks are murdered, often with impunity. It is important that my students know all that because they often take it for granted that the Black American way is the only way to be Black. To wit, many students have asked me what I am, as if my being Black weren’t obvious. When I confirm that I’m Black, they reply that they thought I was Brazilian. Well, “Brazilian” is not a race, and neither is “Latino”! In my classes, I rely not only on history and geography, but on music as well. Du Bois wrote about the “Negro spirituals” as the main source of U.S. popular music. I bring in the fact that African-based music in the U.S. is the only one in the Diaspora that is not drum-based; that is because the slave owners and overseers recognized the importance of drums for communication and suppressed them.

Depending on the course, I may also discuss religious syncretism in Brazil and Cuba, to offset the idea that African religions are about devil worshiping, which is still very strong here in the U.S.

Q) Were you born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil? What was it like growing up there and how did you come to be in the United States?

A) A childhood spent playing in a big yard and plucking fruits from the trees with my sister and my cousins was idyllic. Even though my mother worked for pay full-time, she raised chickens and ducks, so our food was very fresh. She was also a culinary teacher; our birthday parties were delicious. Penha, the neighborhood where I was born, was racially and ethnically diverse: many of our neighbors were Portuguese immigrants, and their children played with us. There was also a door-to- door salesman who frequented our house regularly; he was a survivor of a Nazi concentration camp in Poland. I’m sure my ease with and curiosity about diversity come from my upbringing.

My mother planted in my head the idea of studying in the U.S.. When I was about 11 years old, a number of my friends at school were going to Disneyworld. I wanted to go too, but we had no money for that. My mother said, “Why go now? You don’t speak English, you’ll have no fun. Why don’t you wait and go to graduate school there?” At 19, while I was a student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, a friend told me about a national contest by Encyclopaedia Britannica offering ten scholarships for study abroad. One of the requirements was writing a 25-pp. original monograph. I did an ethnography of a Black Catholic brotherhood in Rio whose members held a strong African ethnic identity. I was the youngest recipient of award.

Q) I have visited Jamaica and the Bahamas, and one of the things that resonated with me is the stark poverty for the people whose resources and rich cultures are exported all around the world. Is this a similar situation in Brazil, and what do you feel is the root cause for this where so many resources exported must be very profitable? Why are these countries considered “third-world” and poverty is so high?

A) The term “Third World” became popular in the 1970s, later replaced by “developing countries.” Before, the same countries were called “underdeveloped.” This hierarchy is determined by Europe and the U.S., a reflection of the legacy of colonialism and the continuation of imperialism. Have you noted that most of the so-called developing countries have large non-White populations? That is not a coincidence. The world system is based on social inequality, racism, and economic exploitation, sustained by an ideology that claims that anything from Europe and the U.S. is better. Portugal invaded Brazil, claimed it as its colony and, for over 300 years, exploited our wood, gold, diamond and other gems, sugar cane, and coffee, all on the backs of enslaved Africans. Brazil has a tiny and very wealthy upper class, a very large poor population, and a small middle class as a result. I would add, however, that I can see signs of that pattern here in the U.S. Despite being considered a “First World” country, the U.S. has pockets of rampant poverty, the middle class is dwindling, and the very rich have become even richer. The difference is that, in Brazil, we assume that economic inequality exists. Here, even the poor believe in the American Dream.

Q) Besides being a professor, you are also an author and a speaker. Tell our readers the names of your books and briefly what they address?

A) I published Pioneiros: Cotistas na Universidade Brasileira (“Pioneers: Quota Students at the Brazilian University”) in Brazil in 2013. That book is based on the research that I did about the implementation of university quotas as part of an affirmative action program in Brazil. I interviewed a sample of the first graduating class of quota students at the State University of Rio de Janeiro, one of the first Brazilian universities to institute racial and social quotas in an effort to decrease social inequality. The policies generated a lot of controversy and quota students were seen as undeserving. I was interested in hearing from the students how they dealt with all that. Last year, I published a revised version of my book in English: Confronting Affirmative Action in Brazil: University Quotas and the Quest for Racial Justice (Lexington Books, 2017). In 2015, I co-edited Religiosidade e Performance: Diálogos Contemporâneos (“Religiosity and Performance: Contemporary Dialogues) with Marcia Contins and Carmen Rocha, also in Brazil. That is a collection of articles on religiosity and identity as they take place in Brazilian urban areas today. There are articles on Afro-Brazilian religious rituals, Catholic devotion, and Evangelical churches, among others.

Q) Where can our readers find your books?

A) All are available on amazon.com.

Q) Are you working on any new material for a book at the moment?

A) Besides academic writing, my favorite genre is the chronicle. I write about day-to- day life constantly, including when I travel. I would love to publish a book of chronicles in the near future.

Q) You are referred to as an “Intellectual Speaker,” having traveled the country as well as South America and Europe speaking at various conferences. What are your speaking topics and what type of conferences do you like to speak at?

A) I have presented my research mostly in academic conferences, but I have also been invited to speak at U.S. and Brazilian universities. With the exception of conferences on Afro-Latina women in New York and Boston in 2006, whose theme was autobiographical, I mostly speak about race relations here and abroad. I would love to break the wall of the ivory tower and venture into non-academic venues as well.

Q) If you were asked to give a commencement speech to the graduating class of 2018 this coming May, what would you like to share for these young people who face a rapidly changing world?

A) I would say to them, “Know about yourself, know about your country, know about the world.” Never has so much information been available literally in our fingertips and yet, fewer and fewer people access it. It pains me when I hear a young person confuse the Civil War with the Civil Rights Movement, for example. It is also baffling that, in this age of “globalization,” so few are familiar with the location of countries outside of North America. Moreover, after a few years of the promotion of the fallacy of a “postracial” U.S., we are witnessing an increase in racial hatred and the murders of unarmed African Americans. As I have mentioned earlier, men and women of African descent are also routinely murdered in Brazil, but most people in the United States are unaware of that.

We need to know our own history and our place in the world in order to develop a healthy sense of self and recognize our partners in solidarity. Only then can we stand against racism or any kind of inequality.

Thank you, Vânia. We look forward to your future works as an author and on the speaking circuits on tour.

Vânia's Photo Gallery

Vânia has authored 2 Books

Confronting Affirmative Action in Brazil Book Review in the American Journal of Sociology

as the ILWU members, to engage in “radical acts of solidarity” (p. 188) with much more vulnerable workers, such as seafaring workers who are mostly Filipino, Chinese, and Indian men and nonunionized Latino and Latina ware- house workers. This is an appealing vision but does not square with the history and ongoing context of white privilege, which the book has so thoroughly documented. Instead, it would be useful for the author to map out how the glob- alization of the shipping industry makes new antiracist approaches to union organizing even more crucial and what kind of radical shifts in racial forma- tion are also required to envision and enact these strategies.

One minor flaw of the book is that it has a very cursory index, just one and a half pages. The lack of a detailed index means that many important general concepts (such as gender and immigration) as well as specific indi- viduals, legislation, and legal cases that are thoroughly addressed in the book are somewhat difficult to find and reference.

In sum, Solidarity Forever is a timely, important, and original contribu- tion to the fields of labor and labor movements, race, gender and class in- tersectionality, immigration, and globalization. It is engagingly written, rig- orously researched, and theoretically sophisticated and would be a useful text for a range of undergraduate and graduate courses as well as a valuable resource to union organizers, policy makers, and workers.

Confronting Affirmative Action in Brazil: University Quota Students and the Quest for Racial Justice. By Vânia Penha-Lopes. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2017. Pp. xii1175. $90.00.

Luisa Farah Schwartzman University of Toronto

In Confronting Affirmative Action in Brazil Vânia Penha-Lopes uses orig- inal interview material, administrative university data, and a wide range of academic research and media sources to provide a detailed picture of what affirmative action looks like in Brazil, the meanings it acquires to different local actors, and the consequences of the policies to the policy’s beneficiaries, the quotistas. The most interesting material, based on qualitative interviews with students at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ)—before and after graduation—offers a window into how these students understand and experience race, racism, and affirmative action. Also valuable are the book’s use of administrative data to highlight quota students’performance at UERJ and its review of Brazilian research on quota students’ performance in Bra- zilian universities more broadly, organized and made accessible to an English- speaking audience here for the first time. Penha-Lopes also provides a de- tailed account of debates about affirmative action in the Brazilian media, and of the political struggles and institutional changes that have accompa- nied these debates.

1266

This content downloaded from 128.111.121.042 on March 09, 2019 15:03:30 PM All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Book Reviews

Penha-Lopes argues that Brazil and the United States are often used as “mirrors” of each other: Brazilian conversations often deploy U.S. race re- lations to convey a lesson about Brazilian race relations, and vice versa. But while debates about Brazil in the United States remain marginalized in specialized academic circles, comparisons with the United States are cen- tral to Brazilian political and public debates. The book also shows the distor- tions that these mirrors present. As an Afro-Brazilian sociologist working in the United States (a rare occurrence thus far, unfortunately), Penha-Lopes is uniquely positioned to look “behind the looking-glass” and to intervene in these two conversations. In the United States, the mirror has traditionally served to question Jim Crow segregation and its legacies and to help push a social constructionist view on race. In the 1990s, U.S. academics shifted and began evoking Brazil to call attention to the dangers of color-blindness: here, Brazil’s blurred ra- cial boundaries are nothing but an evil hegemony—the myth of racial de- mocracy—that obfuscates a racially divided society. More recently, in the 21st century, blurry racial lines have been making a comeback in U.S. soci- ology, in parallel with increased interest in “multiracial” U.S. populations, in colorism, and in the complex racial identities of post-1960s immigrants and their children. The consequences of this new attention to classification and boundaries for race-targeted policies in the United States, however, have not been much explored.

In Brazil, the U.S. mirror image is used to both defend and attack affirma- tive action. For the policy’s opponents, the United States exemplifies the evils of “identity politics,” which purportedly reinforce racial divisions. In this view, affirmative action threatens Brazilian racial conviviality. The pro–affirmative action camp portrays the United States as an exemplar: a place where one can be black and middle class, or even president, and where black people are proud of, and political about, their blackness. Both camps simplify the U.S. situation: for instance, they often say that the United States has “racial quotas,” which characterizes the Brazilian system but not its U.S. counterpart.

But Penha-Lopes also shows that Brazilian affirmative action debates are distinctly concerned with particularly domestic issues. One is the issue of racial boundaries: Do blurred racial boundaries undermine affirmative action as a possibility? Do racial boundaries become more distinct as a result of affirmative action? Is the heightening of racial identity a good or a bad thing? While “identity politics” has also been a controversial subject in the United States, the question of who identifies as black or white is rather mar- ginalized. Other Brazil-specific dimensions of affirmative action that Penha- Lopes discusses include the role of class categories in shaping people’s un- derstanding of affirmative action, the heightened influence that Brazilian university professors have on the public debate on affirmative action, and their own concerns about the kinds of students they will receive in their class- rooms.

1267

This content downloaded from 128.111.121.042 on March 09, 2019 15:03:30 PM All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

American Journal of Sociology

Penha-Lopes’s student interviews corroborate the idea that blurred ra- cial boundaries and “mixed” identities are part their lived reality that, none- theless, often include painful experiences of racism and, of pressure—espe- cially for women—to comply with white aesthetic norms. Thus, racism (and racial identities) can operate through continuous demarcations of the body, of which some characteristics (such as hairstyle) are manipulable. The inter- views, however, also suggest that Brazilians’ understanding of “race” is not just about the racialization of the body, but is often drawn from ideas about lineage, ancestry, and kinship. Thus, racism can exist in the absence of separate “races,” but pigmentocracy does not summarize this either. The big question then is can affirmative action be a solution to racism in such a context? Penha-Lopes only partially resolves this issue. First, she says that affirmative action has had an effect at the discursive level, which is allowing more people to adopt stigmatized identities such as negro or pardo. But she also shows the increasing concern with “fraud” that has per- vaded affirmative action debates, both in the courts and among some black activists that have pushed for the policy. Thus while the initial effect of af- firmative action was to broaden identification as “black,” the subsequent concerns with “fraud” seem to be narrowing it. As I have argued elsewhere, concerns with“fraud,”and the tightening of criteria for affirmative action as a response to it, may work to exclude candidates for arbitrary and unfair reasons. Given these contradictions, what are the implications for how Bra- zil should do affirmative action? As Penha-Lopes herself observed, affirma- tive action policies in the majority of Brazilian universities—and as it was initially implemented at UERJ—allow for a range of racial identities and social experiences to be counted, by including the intermediary categorypardo and by combining racial with public school quotas. Nonetheless, Penha-Lopes dismisses the implications of this insight, saying that public school quotas and the pardo category “dilute” affirmative action, leaving the question open as to the possibilities for affirmative action in the Brazilian context.

What Remains: Everyday Encounters with the Socialist Past in Germany. By Jonathan Bach. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017. Pp. xvii1 259. $30.00.

Lutz Kaelber University of Vermont

A nation’s past can be a formidable resource. Politicians might evoke it in order to bolster their policies, and schoolteachers might include it in their lesson plans to help their students learn from its mistakes. But what if a na- tion, as a juridical construct and sovereign entity, no longer exists? Who gets to commemorate a vanquished nation, and how? How do its former citizens relate to it?

1268

This content downloaded from 128.111.121.042 on March 09, 2019 15:03:30 PM All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Vânia Penha-Lopez Audio Interview

Follow Vânia on: Facebook

We need to know our own history and our place in the world in order to develop a

healthy sense of self and recognize our partners in solidarity. Only then can we stand against racism or any kind of inequality."

— Vânia Penha-Lopes