- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

Causes of World War Two (WWII): Was It Anti-Fascist?

Essay

Although time has rendered world war two as an anti-fascist war there is much evidence to contradict this view. Anti-fascism was definitely a factor but it seems as though it was probably less significant than the prevailing fear of communism and concern over the expansionist policies of the Nazi’s and protection of the empire.

Britain and France’s reluctance prior to 1939 to aid those under threat of Fascist rule in various parts of the world is an indication of their not being as opposed to fascism as thought today. At the time communism was much feared and it was thought fascism was by far the more tolerable option. The occupation of Chinese Manchuria by Japan is an example of this pacification which allowed Fascism to spread. In September 1931 Japan carried out an operation to seize Manchuria after minor damage was caused to a Japanese railway at Mukden. Despite China’s appeal to the League of Nations, in which both Britain and France were highly influential, it was not effectively supported. The final report, which criticised the Japanese, appeared a year later by which time the League of Nations was powerless to take effective action and it’s integrity was damaged. On the subject of Manchuria Churchill, then an MP, said in the Commons 17 February 1933; “On one side…the dark menace of Soviet Russia. On the other the chaos of China”. This sentiment make’s clear Churchill’s resentment of communist states and sympathy towards Japan’s actions. Actions taken during the Spanish Civil war, 1936-1939, also conveyed how communism was perceived. British officials interpreted the democratic victory of the Spanish left in the February 1936 election as evidence of Spain‘s Communist tendencies. The fascist Salazar regime warned the British Ambassador 4 March that “Spain was moving fast towards communism”. Portugal’s Foreign Minister rushed to London to warn Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, of Spain’s apparent approach toward communism which Eden took seriously and influenced British non-intervention policy even when Germany and Italy became involved. Again the anti-communist view of Winston Churchill can be seen in his statement “a communist Spain spreading it’s snaky tentacles through Portugal and France”

A final example of this lack of opposition to fascism which has no communist involvement is seen in Abyssinia. In 1935 fascist Italy began to brutally occupy Abyssinia after fabricating an incident between Italian and Abyssinian troops. Abyssinia appealed to the League of Nations for help but found that the opinions of those in power within Britain supported Italy’s actions. Lord Hardinge viewed the Abyssinians as “a savage barbarous enemy” while Lord Stanhope had said that Britain could not sell arms to the poorly equipped Abyssinians as that “would be going back on the white man everywhere”. Despite these views being felt by those in power the attitude of the British public was very different. The Manchester Guardian wrote of cinema viewings of news of the attack on Abyssinia that; “photographs of Mussolini and his two sons are now the signals for a storm of booing…For the emperor of Abyssinia…there is always a burst of cheering”. This meant that if the British government was to act as it wished it would result in public distrust. Officially therefore, the international opinion had to be of condemnation of the illegal war and so the League of Nations eventually imposed economic sanctions on Italy. However, unofficially both British and French governments broke the economic sanctions and sold oil and war materials to Italy throughout that war. Russia also sold oil to Italy after joining the League of Nations in 1934. The Abyssinians were left isolated and defenceless against the technologically superior Italians. British foreign secretary, Hoare, and French foreign secretary, Laval, formed a secret pact which was leaked to the press on 9 December, 1935. This Hoare-Laval pact offered Mussolini control of two thirds of Abyssinia leaving Abyssinia with what the Times described as only “a corridor for camels”. This was a disappointment to those who had hopes of the League of Nations ending the war and this ‘peace deal’ led to outrage. Fascist Italy’s war continued and in May 1936 Italian troops entered the Abyssinian capital Addis Ababa, successfully conquering Abyssinia. The League of Nations lost respect after failing to protect one of its members from an illegal war.

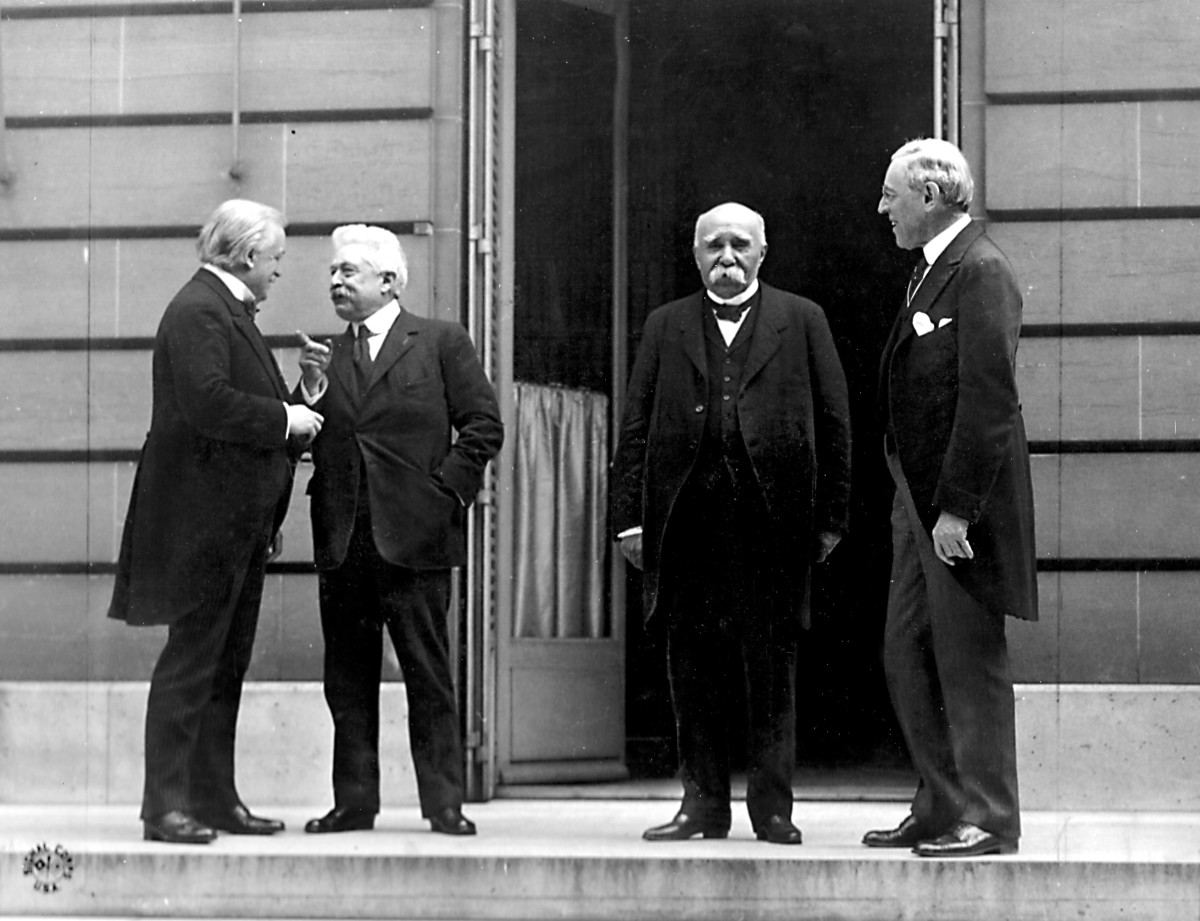

Another key reason for the outbreak of the war was Hitler’s expansionist policy and the threat it posed to the British empire. Both Britain and France had no need to be openly aggressive because of their having previously built up respective empires. Britain and France therefore adopted a policy of appeasement in order to safeguard there lucrative gains. Appeasement though resulted in the allies submitting to the axis powers aggression and withdrawing from upholding the post-WWI system of control set up through a series of treaties signed in Paris (including the Treaty of Versailles) and the League of Nations. Initially in 1935 Britain formed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement which acted to limit rather than stop Hitler’s rearmament programme despite a German navy being banned by the Treaty of Versailles. Britain settled the naval agreement without consulting her allies. The result of this agreement though was that Britain would maintain a level of control and power over the German Navy without conflict. It also meant that Germany would be more limited in it’s capacity to expand. Another example of appeasement allowing Germany to break the treaty is the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, March 1936. This was conducted using the excuse that France had signed a mutual assistance treaty with Russia which Germany found threatening. Britain though did not seem to mind, many politicians believed the Franco-Soviet pact had unduly provoked Hitler and that the Germans were “only going into their own back yard”. Despite this being an expansionist action on the part of Germany, Britain was willing to allow it probably due to the fact that the Rhineland posed no threat to Britain’s own empire. British politicians were clearly not entirely opposed to the ideas of fascist ideology.

In conclusion, although anti-fascism was definitely a factor in the war it was not the only and was certainly not the primary cause. Key British politicians were clearly not entirely opposed to the ideas of fascist ideology. Churchill for example seemed to greatly dislike the Jewish population believing that “the majority of leading figures [in bolshevism] are Jews”. He also said on the matter of Mussolini that he “could not help being charmed.” and that if he had been Italian he would “have been whole-heartedly with you from start to finish.” Clearly, therefore, it was not hatred of fascism which was the prime reason for the declaration of war. Churchill had however always had his doubts about Hitler and vehemently opposed the appeasement policy when speaking in the house. These doubts and resulting wish not to appease Hitler could only have been derived from Hitler’s threatening expansionist policy which would compromise British state interests and consequently the war was not fundamentally an anti-fascist war.