When "Think in English" is Easier Said Than Done

If you are an ESL/EFL student, have you ever been advised that it is not enough that you speak English, but you also have to think in it? Any progress? If your commitment to learning has been giving you gradual steps toward fluency, I salute you. Otherwise, let us find out why it is not working for you.

"Think in English" is a piece of indispensable advice. Thinking about things outside your native language allows you to make better decisions and helps to speed up your thought-processing. Thinking in English also will enable you to learn the language faster. However, you have this habit of mentally translating your thoughts from your native language to English. Doing so would slow down your thought-processing skills because your mind is taking time to translate.

Moreover, if you are still in the stage of grasping the fundamentals of English grammar, mental translation puts you at a significant disadvantage. The sentence patterns in your native language are different from that of English, and therefore, you will be predisposed to construct English sentences using your native language's sentence pattern. This is why many non-native speakers, especially from Asian countries, speak English with total disregard for articles, such as "the," "an," and "a." Articles have no equivalent or are non-existent in Mandarin, Hangul, and Nihongo.

Still, while you are aware of this cardinal rule, you translate mentally, and such habit is persistent among beginner and intermediate levels. Of course, this is not exactly your fault. Your native language is hardwired into your brain, and it has long shaped how you think.

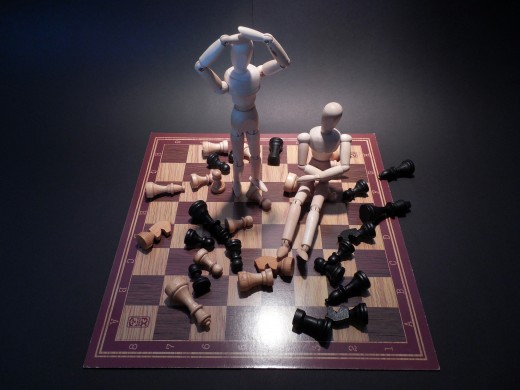

Learning a new language means getting out of your comfort zone and undoing the things you have gotten used to in communicating. Any teacher can champion the virtues of thinking in English, but it all boils down to you. Read these questions and see why you find thinking in English is easier said than done.

1. How do you approach this method?

Do you immediately attempt to construct a sentence, even a simple one? Depending on your level, you may also be tempted to build a compound-complex structure, but your linguistic limitation is a barrier. Make a realistic assessment of your skills. If you are beginning, start with words. If you are already picking up, work with phrases.

Think of the time when you learned to ride a bike. You did not just sit on your BMX and started pedaling at high speeds. No. Surely, you were wobbling on the handlebars, and you bruised your knees a couple of times. Like any skill that takes time, the acquisition of English does not come overnight. Be patient and realistic. Do not compare yourself to advanced learners. You will get there.

2. Are you speaking enough?

If you live in a non-English speaking country, the lack of immersion will be a significant hurdle. You and your fellow natives will not be speaking English to one another, and the sordid fact is that even if you are all learning how to speak English, you will still be speaking in your native tongues because you do not want anyone around you to think that you are possessed.

This inhibition to speak English is an issue for you to resolve. If you want to spare yourself from such embarrassment, try talking to yourself in your room. Assume the role of an actor. Speak English before a mirror. Do this every morning or before going to bed. Make it a habit. It only takes twenty days to form a habit. If you can do this for twenty days, you will be doing it continuously.

3. Are you afraid to make mistakes?

This takes us back to the bicycle analogy. You learn a language in increments, not in a single go. In learning any language, either you use it, or you lose it. You have to forgo of any inhibitions and use it. You have to start somewhere. Making mistakes is part of learning. Expect that there will be people who will call your attention to your grammatical boo-boos.

Regardless of whether they did it to ridicule you or as a gesture of constructive criticism, will you let it affect you? When you were a child, remember how your parents reprimanded you for playing in the rain because you might catch a cold, or that you were grounded for a week for breaking your curfew? Did you take these things personally and let it affect you while you were growing up?

4. Do you take time to listen?

Man is a social animal, and we learn by mimicking how others on how to do things. Part of immersion is listening to how English speakers use the language. Pay attention to how they string words and phrases together. Note down words or phrases that you are not familiar with. Listening helps you to identify keywords, and it is the basis for your speaking, reading, and writing skills as well. Listening also helps you to use your general knowledge and polish how you fish for context.

You would probably say that you live in a country where English is not spoken, so there is no one you can you listen to. That could be a valid excuse twenty or thirty years ago. With the advancement of technological communications, such excuse no longer carries weight. This takes us to the next question.

5. What type of tools and reference materials are you using?

Podcasts and videos are accessible online and are great tools for honing your listening comprehension. You are wired and connected wherever you are in the world. Online English courses are readily available as well. You can join groups on social media with similar language learning interest.

Reference materials like dictionaries and encyclopedias can be found online and on your tablets and smartphones. But here's a caveat: Choose your reference tools wisely and carefully. Some dictionary and thesaurus apps do not have enough word entries. Similarly, there are cheap electronic dictionaries that only provide literal definitions and not how a word is used in slang or figurative sense.

In some contingent purpose that you might find the need to translate from your native language to English, Google Translate can prove useful for words or phrases; but for longer sentences, do not count on it too much. It operates on Statistical Machine Translation, gathering texts that are equal in meaning between two languages, and hence, long sentences get off-the-mark translations.

You can ask yourself questions on why "think in English" is harder in practice than in theory. By addressing the above issues, you are well on your way to re-assessing the way you learn English and get a better grasp of how to "think in English."