Why are Smart Kids Unpopular?

Check out the new second edition of my book:

A revised version of this essay is included in the recently published, second edition of my (Freeway Flyer/Paul Swendson) American history book. If you click the link below, it will take you to a hub that provides more information.

Peer Pressure: Where does it come from?

I am not sure when it happened, but at some point in my life I stopped caring so much about what other people think about me. By virtue of being human, I will always experience a certain amount of self-consciousness. But these neurotic tendencies are nowhere near the level that they were in high school, or even college. This change may be part of the natural process of becoming an adult. Over the years, I have noticed that my older students are far less inhibited than the younger ones. These older students are so uninhibited, in fact, that it is sometimes hard to get them to shut up. I think that my personal reduction in self-consciousness, however, is also the result of spending about seventeen years in the teaching profession. Because in this job, you cannot be very effective if you care too much about what others think of you.

Excessive self-consciousness is one of the strongest impediments to education in American culture. It can sometimes be a problem for teachers, although I suspect that teachers who are always seeking approval from students do not last very long. The main concern is its impact on students, a phenomenon commonly known as “peer pressure.” In American culture, peer pressure may be the most common explanation for an assortment of behaviors, particularly with young people experiencing “adolescence.”

One of the ultimate examples of the impact of peer pressure, of course, is the attitude of many adolescents toward school. Because for “teenagers,” school is one of the ultimate evils of the universe, most likely in a close tie with parents (and old people in general). The last thing a young person wants, after all, is to receive one of the many negative labels that our culture has produced for people who do well in school, terms such as “nerd,” “geek,” “brown nose” or whatever the current terminology may be. On the other hand, many students take pride in academic failure, bragging about their poor study habits and lousy grades. Now in college teaching, you would think that this is no longer a problem. After all, college students are in school by choice. In some cases, however, I still have students who have not broken out of this “adolescent” way of thinking. These students are still trying very hard to present the image of a person who does not care, and they often pay the price when they play this role too well. Of course, this explanation for student failure fails to answer a simple question: why does peer pressure often push young people in a negative direction? Why is there often so much hostility toward school?

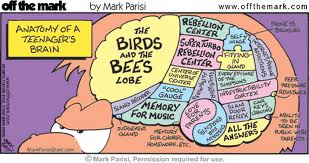

Now I would never claim to be a psychologist, but I am somewhat familiar with common psychological explanations for adolescent behavior. There is of course the “raging hormone” argument, which has been used, with some accuracy, to explain all sorts of irrational behaviors. Hormones, for example, may cause adolescents to think a bit more about the opposite sex (and sex in general) than academic pursuits. They may also lead to emotional outbursts that interfere with human reason. Another of these “biological arguments” focuses on the particular qualities of the adolescent brain. I have heard more than one expert over the years arguing that the teenage brain is not fully developed, with the “common sense” part of the brain not reaching full maturity until a person is in his or her mid-twenties (and sometimes never). Some would also argue that adolescent behavior is a natural part of the transition to adulthood. An attempt to assert one’s independence should be expected of people in this age group, and this is not necessarily a negative thing.

Youth Culture & Public High Schools

In my view, all of these psychological explanations have a certain amount of validity. As a History teacher, however, I am inclined to look for historical explanations for behavior. Could modern adolescent behavior also be a product of historical forces and not just a result of teenage biology? In my American History classes, there are two units in which I directly address the issue of adolescent hostility toward academics. One unit where this topic comes up is the 1920’s, a time period in which a distinct American “youth culture” was starting to form. This term “youth culture” refers to the development of a distinct way of life among so-called “teenagers,” involving certain types of dress, speech, music, and other behaviors. Today, it is taken for granted that young people in America want to develop a way of life that is different from their parents and from old people in general. The quickest way for something to become “uncool,” after all, is for a teenager’s parent to start liking it.

So why did this particular way of life begin to appear in the 1920’s as opposed to some other period? It seems that the appearance of this youth culture coincided with the development of public high schools and the increasing perception that a high school degree was crucial for success. The only way, after all, for adolescents to develop a distinct way of life was for them to have the opportunity to spend large amounts of time exclusively with other adolescents. (In addition, the growing prevalence of automobiles at this time created opportunities outside of school.) In the past, people in this age bracket never had the chance to hang out so often with exclusively teenage friends. In the nineteenth century and earlier, fifteen-year-olds may have been working on the farm, learning skills as an apprentice, or working as a manual laborer. In other words, they had somewhat made the transition to being an adult, and they were spending time in the adult world.

Now let us return to the raging hormones. Biologically, adolescents are becoming adults in their teenage years. In modern American society, however, they are not recognized as such. Instead, they are bottled up in high school, unable to make much of a contribution to society until they get that high school degree. Today, in an age where the college degree is seen as increasingly mandatory, young people are bottled up in school even longer .It can be very difficult to make a decent living on your own in America until you are in your mid-20’s, and in many fields – medicine, law, college teaching – the wait is even longer.

The biological definition of an adult, therefore, no longer matches the cultural definition. And because of this disconnect, we have a society that is populated by a large number of frustrated “wanna-be” adults who are stuck in school. It is only natural, then, that high school and sometimes even college students will lash out against educational institutions. Of course, “teenage rebellion” is directed against more than just school. If you look at a list of the behaviors that many – not all, of course – adolescents think are “cool,” you will see a list of some of the dumbest behaviors that a human being can engage in: drinking oneself into oblivion, driving like a maniac, having unprotected sex, and doing extremely dangerous things for no apparent reason other than showing off your “coolness.” To a certain degree, I think that teenage frustration is directed against authority in general. Authority figures, after all, are older people seemingly impeding the entrance of young people into the adult world.

The Jacksonian Era & Anti-Intellectualism

To understand this anti-school phenomenon, however, you must look beyond a discussion of adolescence and recognize a broader aspect of our American cultural heritage. So it is here that I bring up the second American History topic that relates to anti-school hostility: the Jacksonian era. When historians speak of the Jacksonian era, they are referring to American political history of the 1820’s and 1830’s, a period in which Andrew Jackson was the most influential political figure. It was also a period in which The United States became a somewhat more democratic nation, a phenomenon Jackson would take advantage of in his rise to power.

When our country was founded, only a small percentage of Americans had the right to vote. The majority of Americans were disqualified for a variety of reasons. Women and slaves were ineligible throughout the United States, and in many states even free black men were disqualified. Many other states, as had been common in colonial times, required that an individual owned a certain amount of property to be able to vote. The typical voter, therefore, was a white, male, and free property holder.

In the early nineteenth century this situation gradually changed as a movement grew in support of “universal white male suffrage.” In other words, people pushed for the elimination of the property requirement mentioned previously. (Other barriers to voting, of course, still generally applied.) Most of the new western states that were rapidly being created established themselves without these property requirements. Over time, many states in the east were pressured to do the same. And as an increasing number of “average guys” gained the right to vote, politicians began to adapt their campaigns to appeal to this new kind of voter.

This movement toward democracy, however, involved more than simply changes in voting rules. It was also an ideological movement in which people came to believe that average, everyday Americans should have more of a say in the political system. When our country was founded, many Americans felt that citizens should defer to higher status people whose success and educational backgrounds qualified them to rule. Our founding fathers – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison – generally came from this class of people. By the 1820’s, however, many voters, particularly these new non-property holding voters, came to see elite status as more of a negative. A person with a large amount of wealth and education, after all, would be out of touch with the needs of the “common man.”

It was in this environment that Andrew Jackson rapidly rose to prominence in the 1820’s. While he was hardly a common man, he effectively presented an image that common men found appealing. Jackson was a farmer, a westerner, and a war hero. He was a self-made man, not a person born into wealth and status. He was also a man that even his supporters would never describe as a great intellectual. Some would describe the rise of Andrew Jackson as the beginning of “mass politics.” Campaigns from that point forward utilized techniques that appealed to the masses: rallies, parades, picnics, catchy slogans, and the careful cultivation of a candidate’s image. Jackson then rewarded his supporters by hiring them to political positions, signifying even further the entrance of the average guy into politics.

So what does this nineteenth century history lesson have to do with modern education? This historical discussion began as an attempt to figure out why many young people are hostile toward education. I then proceeded to explain how early twentieth century adolescents began to create their own distinct sub-culture. Now while I still hold to my teenage subculture thesis, I also believe that the adult dominated, broader American culture still manages to impact adolescents. And as much as older Americans preach the importance of education, there is to this day an anti-intellectual, anti-elite bias in American culture that can be traced back to the days of Andrew Jackson.

To see this, just look at recent political campaigns. George W. Bush, in my mind, is an excellent example of a Jacksonian politician. Like Jackson, he is hardly a common man. Most people were not born into the wealth that his family possessed. Most do not have a father who was recently president. And yet he did a very effective job of appealing to the average American voter. More than once I heard voters say that George Bush seemed like a guy you could have a beer with. His famous grammatical and pronunciation “issues,” rather than being detrimental, may have helped him cultivate this image of the average guy. On the other hand, Al Gore and John Kerry were caricatured by the Republican Party as stiff, snobby, liberal elites. (Their lack of anything resembling charisma only served to strengthen the caricatures.) Even Barrack Obama, an African-American man raised by his single mother and grandparents, was described by Republicans during the 2008 campaign as a member of the liberal elite. His Harvard degree, a degree I assume he earned through intelligence and hard work, was seen by many as evidence of his elitist attitude. Then, in this same campaign, Republicans turned to Sarah Palin, the ultimate example of the candidate designed to appeal to the “average” voter. She, after all, was a “soccer mom” just like millions of Americans. She also talked the language of the average voter, and she did not have all of those fancy degrees or elite political credentials.

Now you may be wondering why I have suddenly degenerated into a stereotypical liberal professor promoting the Democratic Party. Believe it or not, this is not my point. I am merely trying to demonstrate that “elite” status, something often associated with intellectual achievement, is often viewed negatively in American culture. And in a culture that often describes educated people as arrogant, out-of-touch nerds, it should not be surprising that young people pick up on some of this anti-intellectual hostility. Personally, I find this general hostility toward “smart” people disturbing. I want highly educated, intelligent people running for high office. I do not particularly want average guys (like myself) running for congress and the presidency. Most of us “average guys” are not remotely qualified for these jobs. This does not mean, of course, that a fancy degree in itself qualifies a person for political office. It also does not mean that a person without impressive educational credentials should be instantly disqualified. There is much more to life experience, after all, then “book learning.” But holding intellectual achievement against someone is simply ludicrous.

Final Thoughts

Having made these various arguments, a part of me wonders if I have made all of this too complicated. It is possible, after all, that people simply dislike school because it is so difficult and monotonous. Once you have stopped being a student for a while, it can be easy to forget how hard it was to get through school. This can be particularly true for teachers, who after many years can forget what it was like to be the test taker. It is important, therefore, for teachers to try to maintain a certain amount of empathy for students. The majority of my students, after all, are still growing up in a culture where it is hard to become an adult. They are also trying to become educated in a society that often does a poor job of helping them, either because of poor teachers or because a quality education can seem increasingly unavailable or expensive. In addition, they listen to preaching from adults about the importance of education in a society that continually uses negative terms to describe intellectuals. In short, it is not easy being a student, especially when you are young (and those damn hormones keep raging).