- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Road to Wounded Knee December 29,1890

The Great Sioux War of 1876

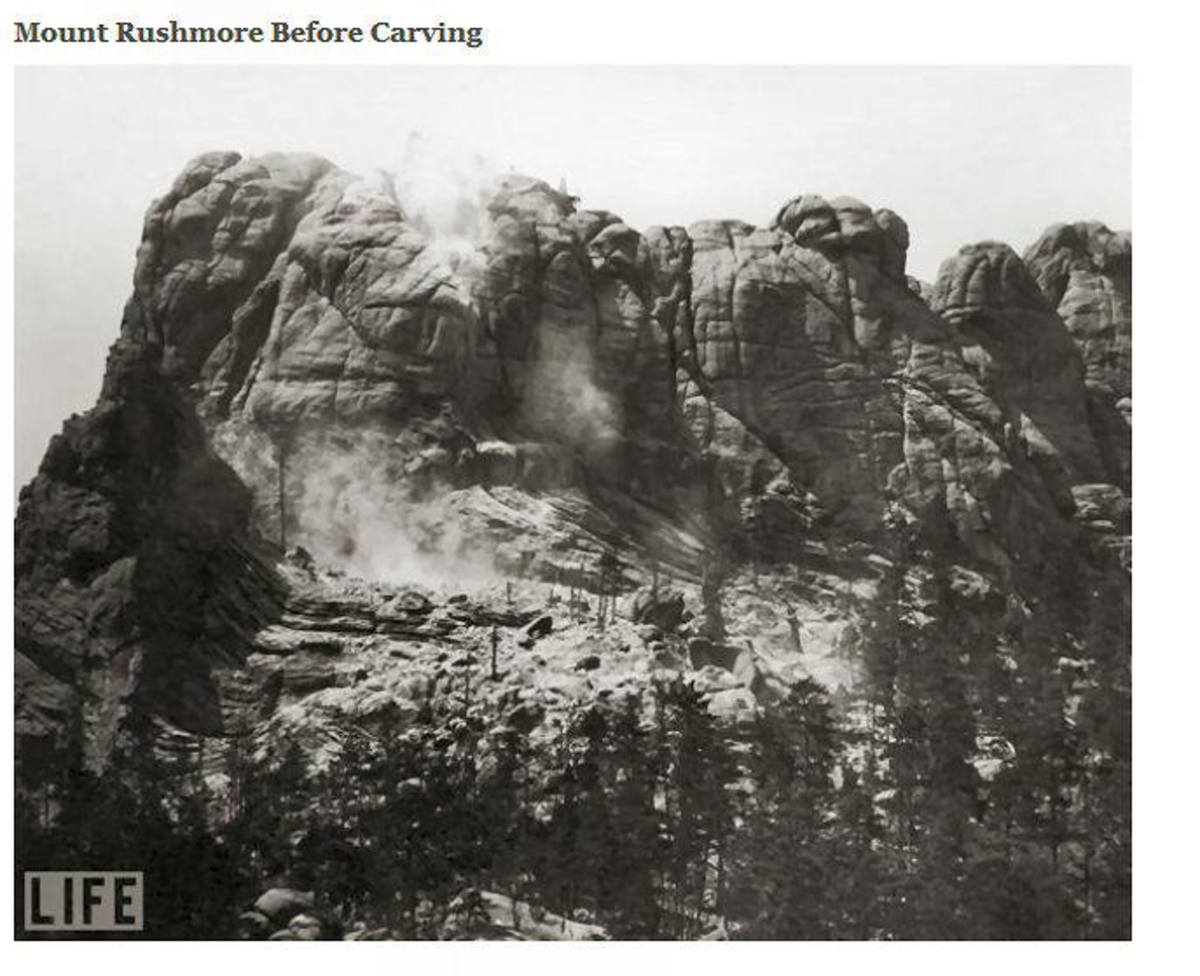

The Northern Great Plains were the last refuge for Native Americans fleeing the waves of European settlers from the eastern United States. By 1900, the indigenous population of North America would decline by 98% since the arrival of Europeans in 1492. These settlers were primarily motivated by the desire to exploit Native American lands, including the gold-rich Black Hills. In early November 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant met with General Philip Sheridan and others at the White House to discuss Indian policy. They issued an ultimatum requiring all Sioux outside the reservation to move there by January 31, 1876, or be deemed hostile.

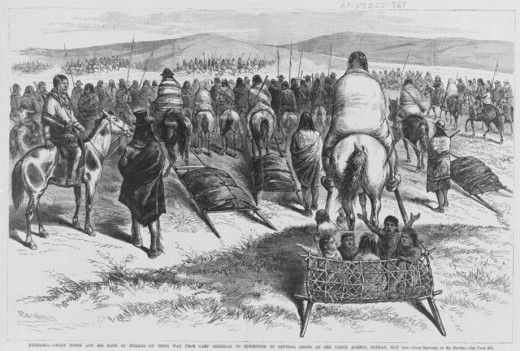

The Sioux ignored Grant's ultimatum, leading the American military to initiate a campaign aimed at rounding up all hostiles and returning them to the reservation, an operation later called the Great Sioux War of 1876. Many Native Americans were compelled to abandon the harsh conditions on the reservations and join Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse to live their traditional way of life near what is now the Powder River Basin, due to insufficient food, housing, and outbreaks of disease.

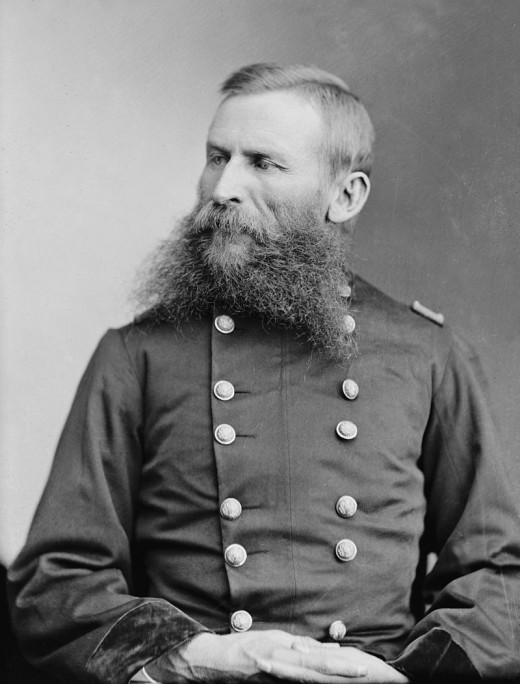

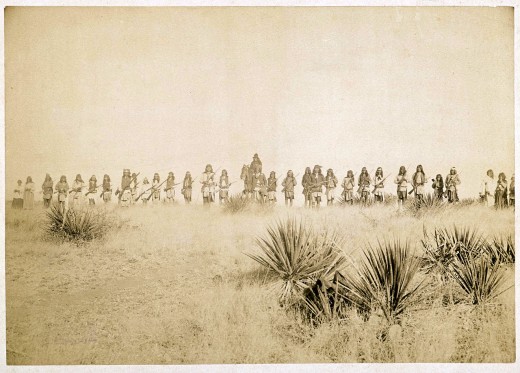

In 1872, General George Crook led American troops on a mission to subdue some of the last free-roaming Apache bands in the southwestern United States. His goal was to round up the hostiles and place them on reservations. Crook's effective use of Apache scouts and mule pack trains played a key role in the success. The relentless winter campaign of 1872-1873 ultimately brought an end to most of the conflict.

After General Crook's success in the Arizona Territory, General Phil Sheridan, believing Crook relied too heavily on the Apache scouts, replaced him with the boastful General Nelson Miles, who essentially followed Crook’s strategy. In 1875, the War Department assigned Crook to lead the Department of the Platte. His mission was to capture the followers of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Crook's jurisdiction covered Nebraska, as well as parts of Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho. When Major General George Crook passed away in 1890, Red Cloud, the Oglala Lakota war chief, honored him with a profound tribute, saying, “He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope.” Crook's new assignment would leave him with a lifetime of regret.

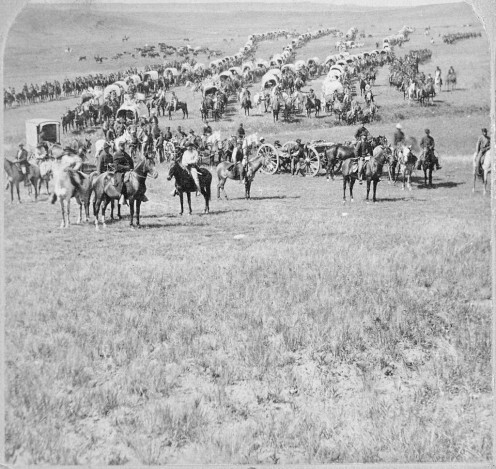

Due to the harsh winter conditions and the remote location of Sitting Bull's village, most of the intense battles of the Great Sioux War took place in late spring of 1876. In June of that year, General Crook took command of one of three columns of soldiers advancing toward the Little Bighorn region in southern Montana. General Gibbon's column approached from the east, departing from Fort Ellis in the Montana Territory. Meanwhile, General Alfred Terry's column, which included about 570 men and the soon-to-be-famous 7th Cavalry under General George Custer, marched westward from Montana. Altogether, the combined forces totaled 2,500 soldiers, making it the largest American military effort against the native tribes of the northern plains at the time.

Black Hills Gold Rush

Rosebud Creek

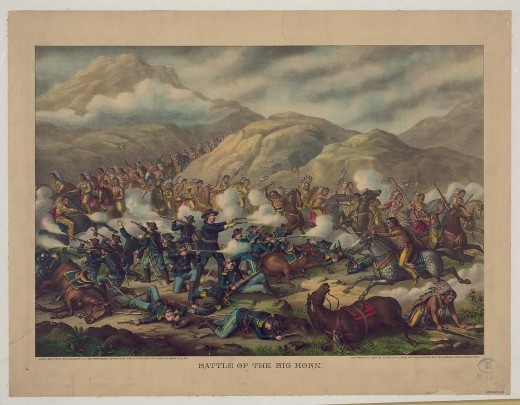

The three armies assigned to capture Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse's Sioux band planned to converge in the Big Horn River valley. However, attacking an enemy whose location and size were uncertain proved to be a major challenge. The vast distances and unreliable communication made it nearly impossible to coordinate their meeting point.

The plan quickly began to fall apart. As Crook's force neared the Big Horn, his Crow scouts reported signs of a large Sioux force nearby. Crook was convinced the Sioux were gathered in a sizable village along Rosebud Creek, just north of the Big Horn. Like many of his fellow officers, Crook believed the Sioux would likely flee rather than fight and was determined to locate the village and strike before they could escape into the rugged terrain. However, his scouts—262 Crow and Shoshone warriors—were more cautious. They suspected the Sioux force was under the command of Crazy Horse, a brilliant war chief. They warned that Crazy Horse was far too clever to allow Crook the chance to attack a stationary village. Crook soon discovered his scouts were right.

Around 8 a.m. on June 17, 1876, General Crook halted his force of about 1,300 men in a small valley along Rosebud Creek in southeastern Montana, near what is now Sheridan. This pause allowed the rear of his column to catch up. His troops included 10 full cavalry companies and four infantry companies, forming a well-trained and disciplined unit.

Unaware of any threat, Crook's soldiers unsaddled their horses to let them graze as the troops relaxed, enjoying the cool morning air. The force was scattered, exposed, and unprepared for what was coming. Suddenly, a group of Native American scouts burst into the camp at full speed, shouting, "Sioux! Sioux!" Within moments, a large group of Sioux warriors began closing in on the army.

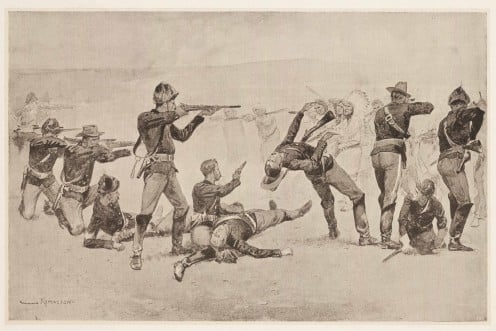

A force of at least 1,500 mounted Sioux warriors surprised Crook's soldiers, while Crazy Horse held an additional 2,500 warriors in reserve to complete the attack. Fortunately for Crook and his men, 262 Crow and Shoshone scouts had positioned themselves about 500 yards ahead of the main force. With incredible bravery, these scouts launched a countercharge against the much larger Sioux force, delaying Crazy Horse's initial assault long enough for Crook to regroup and send reinforcements. Soon, Crook's soldiers were locked in a fierce hand-to-hand battle for survival as Crazy Horse and his warriors surrounded them.

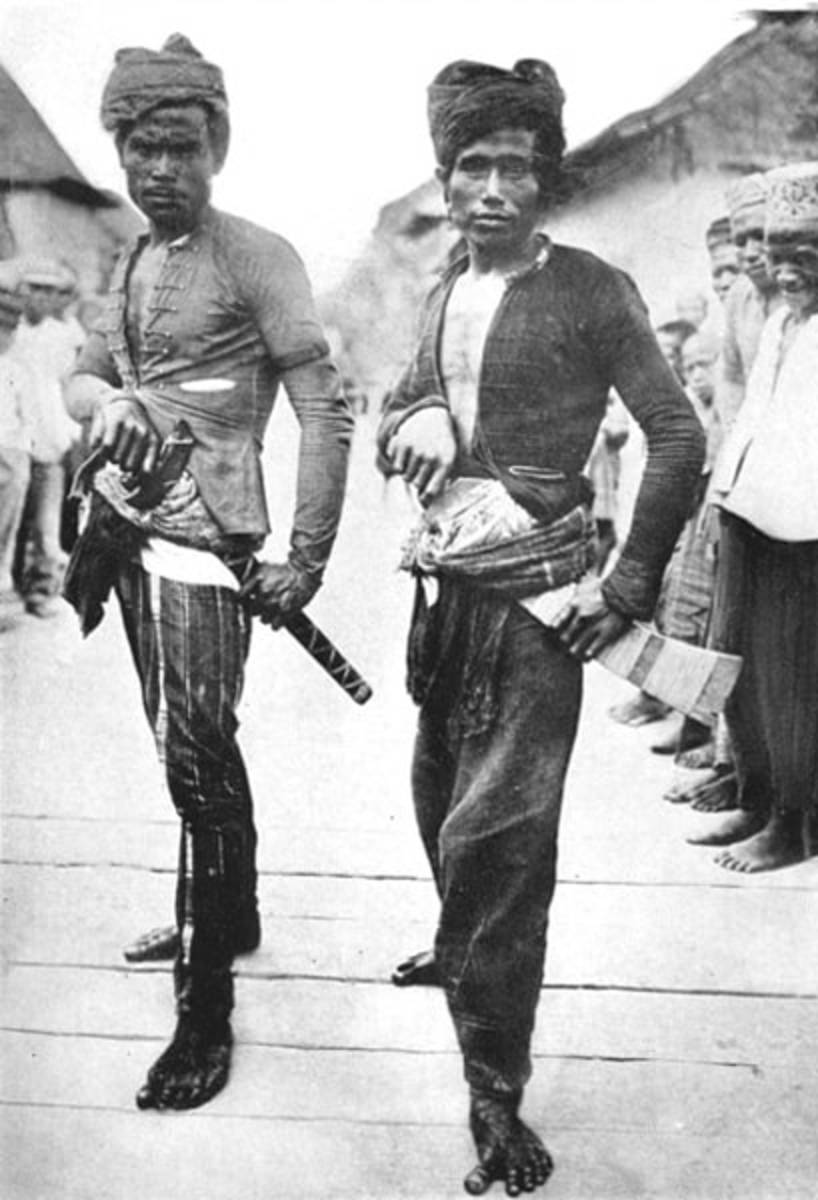

Crazy Horse's warriors were more heavily armed than ever, with possibly one in four carrying a rifle. The Sioux proved themselves to be some of the finest soldiers of their time. As they charged their enemies, they exposed very little of their bodies. By clinging to their horse's neck with one arm and draping a leg over its side, they attacked with firearms and lances from beneath the horse's neck, leaving no target for their enemies to strike.

Crazy Horse's warriors attacked Crook's force not in a straight line but in clusters, resembling herds of buffalo. He devised a new strategy that brought success in the Battle of the Rosebud and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. By holding his warriors back and sending them in waves from different directions, he forced the soldiers into smaller, scattered groups defending isolated parts of the battlefield. The retreat tactic lured some soldiers forward, leaving them vulnerable to attacks from multiple sides. Arrows rained down on Crook's troops and horses, creating a deadly barrage. The battle lasted over six hours and consisted of several disconnected skirmishes, with the two forces spread out across a shifting front over three miles.

Crook's army suffered heavy losses, with over sixty-four men killed or wounded, forcing him to retreat and regroup. Crazy Horse, on the other hand, lost only 13 warriors and gained confidence from the successful attack. The ambush left Crook's forces defensive and hesitant to advance into hostile territory. Many argue that Brigadier General George Crook met his match at the Rosebud, as Crazy Horse and his warriors skillfully countered him. Crook spent the rest of the campaign fishing and hunting, avoiding further moves toward the Little Big Horn valley. Eight days later, Crazy Horse and his warriors joined Sitting Bull at the Big Horn, leading to the total defeat of George Custer and his 7th Cavalry.

Wounded Knee

In 1871, buffalo still roamed the Great Plains freely. That year, a herd of four million was spotted near the Arkansas River in what is now southern Kansas. The herd's main body stretched fifty miles deep and twenty-five miles wide. Once, over 20 to 30 million buffalo inhabited the Great Plains, from present-day Texas to the Canadian border. Within just a decade, these majestic animals would face near extinction, and Native Americans would lose their traditional way of life.

The US Army was deeply involved in one of history's largest near-extinction events, even providing free ammunition to buffalo hunters. Beginning in the 1860s, a conflict unfolded on the Great Plains as the Army sought to suppress native tribes to pave the way for white settlers and railroad construction. Federal officials understood the vital role buffalo played in the daily lives of indigenous people. By 1890, only 1,000 buffalo remained, with Yellowstone National Park housing the last wild herd in the United States. Hungar and desperation eventually forced Sitting Bull and his followers to return to the United States and surrender on July 19/1881.

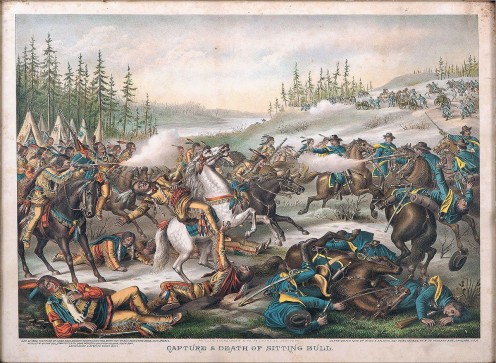

On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was killed by Indian policemen near his cabin on the Standing Rock Reservation, which spans the border between North Dakota and South Dakota. A close-quarters fight broke out during their attempt to capture him, and within minutes, 14 men were dead and two others fatally wounded. The Indian policemen killed Sitting Bull and seven of his supporters. His body was transported by wagon to Fort Yates on the reservation, where it was wrapped in canvas and quietly buried in a remote corner of the post cemetery. Two weeks later, on December 29, 1890, the 7th Cavalry massacred a group of Ghost Dancers led by Big Foot at Wounded Knee in South Dakota, effectively ending one of history's greatest resistance movements.

Sitting Bull and other Plains Indians' resistance played a key role in the rise of the Ghost Dance movement. This peaceful political movement symbolized Native American opposition to the US Army's efforts to suppress their traditional way of life. In the 1890s, the Ghost Dance movement spread across the western United States and became linked to the Wounded Knee Massacre.

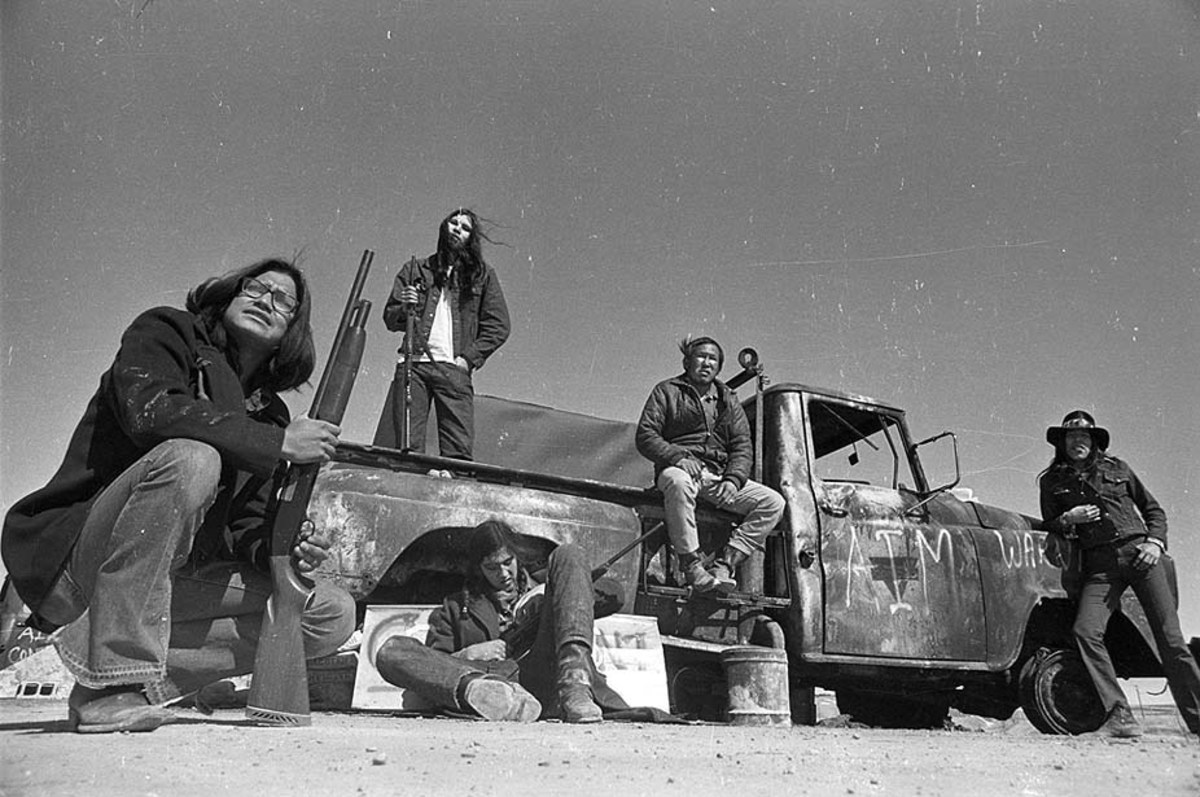

On that fateful day at Little Bighorn, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and Gall emerged victorious in battle but ultimately lost the fight to live as free men. They were forced to exist as though they were merely shadows of their former selves. Their people and way of life teetered on the brink of extinction. Even today, the Indigenous peoples of America live on reservations assigned to them by the United States government.

Sources

Ambrose Stephen E. Crazy Horse and Custer: The Epic Clash of Two Great Warriors at the Little Bighorn Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 1ST Floor 222 Gray's Inn Road London WCIX 8HB. 1997

Hoig Stan. The Battle of Washita: The Sheridan-Custer Indian Campaign of 1867-69. University of Nebraska Press. Doubleday Garden City N.Y. USA 1976

Philbrick Nathaniel. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Penguin Books 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014 USA. 2010

Welch James. Killing Custer: The Battle of the Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 USA. 1994

This content reflects the personal opinions of the author. It is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and should not be substituted for impartial fact or advice in legal, political, or personal matters.

© 2025 Mark Caruthers