Beyond Native: How Learners Teach Better

Beyond Native: How Learners Teach Better

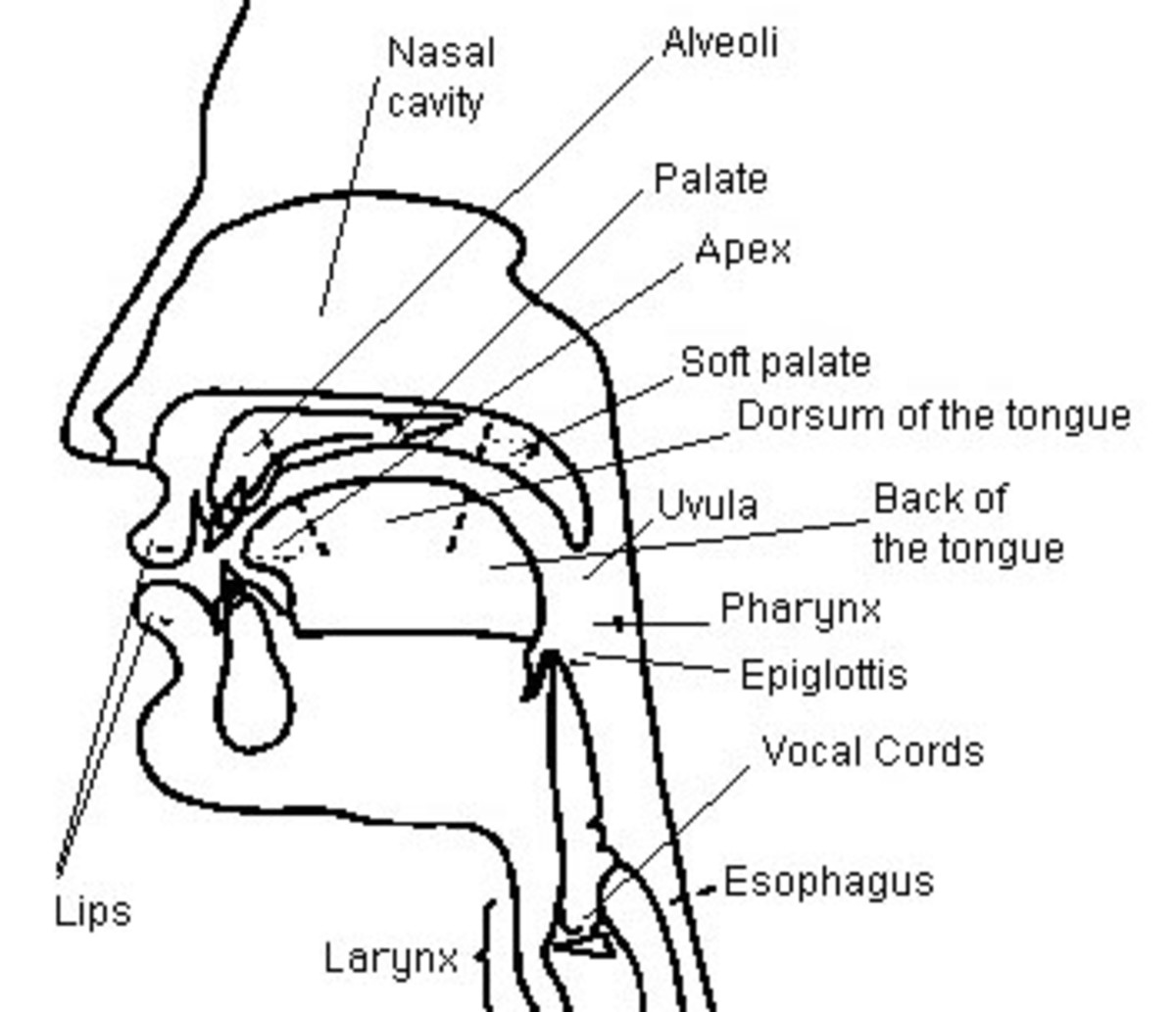

When students or hiring platforms look for a language tutor, there’s an automatic reflex, almost instinctual: "Must be a native speaker." It sounds like common sense, right? Who better to teach you a language than someone who grew up breathing it in, soaking it from their cereal box to their lullabies? But here's the plot twist: when it comes to actually mastering the building blocks of a language — grammar, vocabulary, and especially navigating the rocky road of being a beginner — non-native speakers might just be your secret weapon. They understand the anatomy of language not by intuition, but by dissection.

They didn't inherit fluency; they earned it.

Let me break it down: I was born in a mixed Hungarian-Serbian household, bilingual from the get-go, dodging cases and conjugations like linguistic landmines. Before I turned ten, I was also already getting acquainted with both German and English. Later on, I majored in Japanese at university, threw in some casual Spanish and Korean, and found myself constantly juggling the ever-growing chaos of multilingualism. And here’s an odd, but universal truth I learned: the brain has a favorite child. Once you're fluent in four or more languages, keeping all of them equally sharp becomes an Olympic sport. If you neglect one, it shows. It sulks in the corner, forgets its irregular verbs, and serves you the wrong pronoun in the middle of a sentence. Prioritize another? It thrives, blossoms, picks up cool new slang like a sponge.

...But here's the second, oddly comforting fact: true fluency doesn’t vanish overnight. Even if I go months or years without speaking, say, German, stray vocabulary will still pop up uninvited. A phrase, a collocation, a random grammar rule you forgot you ever knew — it'll ambush you while you're brushing your teeth or trying to say something in Japanese. That's language memory for you. It's a ghost that never fully leaves the house.

...Now, let me confess something: I studied German formally for four years, two times a week. At the same time, I was independently learning Japanese and Spanish through online rabbit holes and binge-listening to foreign music. By my fourth year of German, when I was put on the spot to form a sentence, it wasn't a German word that came to mind. It was Spanish. Or worse, Japanese. My mouth was an international airport without customs control. I realized then: even if you’re naturally gifted for languages, each one sits with you differently. Some, you absorb effortlessly, as if they’re old friends from a past life. Others resist you at every step, remain foreign, distant, emotionally gray. German was that for me. Whether it was because of the complex grammar or simply my personal disinterest, I never felt at home in it. At one point, while forming basic German sentences, Japanese pronouns would randomly hijack my thoughts. My linguistic wires were crossed. This experience taught me that even among multilinguals, fluency isn't democratic. Some languages stick. Others slip through the cracks of your mind no matter how hard you study.

So, what does all this mean for language teaching? A lot, actually. At university, I had both native and non-native Japanese teachers. And the dynamic was illuminating. Our Serbian-native Japanese teachers understood our struggles intimately. They’d walked the same road, stumbled over the same awkward particles, misused the same honorifics, and confused similar kanji. More importantly, they could explain these hurdles. In Serbian. With comparisons and parallels that made intuitive sense to our ears. They offered techniques that only someone who learned the language as a second language could.

Contrast this with some of our native Japanese instructors: incredibly fluent, yes, but often bewildered by our questions. When we asked, "Why does this particle go here?" they'd repeat the textbook answer or simply say, "That's how it's said." Which is valid — but not helpful when you’re trying to build understanding from scratch. When we needed clarity, it was the non-native teachers who stepped in with metaphor, mnemonic, and method.

...And let me tell you about the Korean fiasco! I tried studying it as an extra class in uni. Our teacher was a Korean exchange student who majored in Serbian. A nice guy, but with zero teaching experience or interest in teaching Korean. The course was a hot mess. He couldn't answer our questions. He didn't explain how or when to use words, only how to pronounce them — and even that, he hyperfocused on, nitpicking while ignoring context. We didn’t need a pronunciation coach. We needed a guide, someone who could lay down a foundation. It showed me that being a native speaker isn’t enough. It never is. Teaching is a craft, not just a skillset. It requires patience, pedagogy, and deep meta-linguistic awareness..

That said, native speakers do have their strengths. They're unmatched when it comes to subtleties: tone, implication, whether a phrase is stiff or smooth, dated or chic. They live the idioms, breathe the nuance. But guess what? Those skills can be absorbed too. With exposure. With time. With dedication to media, conversation, and listening. They're not off-limits to learners.

So, why, then, does society place native speakers on pedestals? It could be perception. We assume native equals perfect. It’s branding, pure and simple. A shorthand for authenticity. There's also the comfort of knowing you’re learning from "the source," which gives people a false sense of linguistic security. It’s part prestige, part illusion. We equate birthplace with ability, without considering teaching skill, empathy, or actual fluency in grammar.

...But what if we shifted our mindset? What if we acknowledged the power of someone who has learned the language to teach it? Someone who remembers what it was like to struggle. Who knows where you're likely to trip, and who’s got a lantern and map ready for you because they’ve made that same trek. Someone who doesn’t just speak the language, but has decoded it, wrestled with it, learned to dance with its rhythm and stumbles.

Non-native teachers often:

- Have a clearer understanding of grammar, because they had to study it

- Know multiple explanations for the same concept

- Empathize with your confusion

- Offer learning tips specifically tailored for people coming from your language background

- Are often more intentional about teaching, since they had to be intentional about learning

- Use diverse resources and strategies, drawn from their own learning journeys

- Anticipate common mistakes because they've made them too

To end this on a hopeful note: If you’re a language learner, don’t underestimate the value of a non-native teacher. Look for passion, understanding, and communication skills over accent and passport. If you’re a non-native teacher, own your strengths. Your journey is your superpower. And if you, like me, live in a linguistically chaotic headspace, treasure it. Every mixed-up phrase, every unexpected vocab flash from a neglected language, it all means your mind is alive with possibility. Languages aren’t trophies to be polished and put on a shelf. They’re tools, messy and magnificent. And those who learned to build them from scratch? They know how to hand you the blueprint.

© 2025 Monika Pavlov