Memory and Memory Distortion Interviews

Emotional Processes Across the Adult Life Span: Susan Charles

"

1. How did you become interested in psychology?

>> Well I decided to pursue a career as a psychologist who does research and is a professor of psychology because I think all of us in this country are raised with the idea that we're individuals and that everyone has unique physical attributes and perky personality traits and our own likes and dislikes and then when you start reading about psychology, you realize that this random chaos of behavior actually can be very organized and systematic and predictable and I enjoyed reading about psychology and understanding the patterns of development and the patterns of behavior and I realize that's what I wanted to study. And as far as being a professor, the goals of the academy are to teach students how to think critically and once people do that they never look at the world in the same way and it's really a marvelous phenomenon to watch and witness.

2. What is your current area of research?

>> I study emotional processes such as emotion regulation and how emotion regulation changes across the adult lifespan.

3. Can you explain the” socioemotional selectivity theory”?

>> Socio emotional selectivity theory is a theory that posits that our goals and motivations are shaped by our perceptions of time left in life so according to the theory, most of human behavior is directed by two overarching sets of goals. The first, our knowledge based and knowledge related goals and the second are emotion goals, the striving for emotional meaningness and satisfying experiences. So according to the theory, when we perceive a expansive long future ahead of us, our goals are motivated to expanding our horizons and seeking information and knowledge that we can then use for this long time ahead of us and once we see that the time left in life is running out, growing shorter, instead we focus our goals on emotional meaningful experiences and deriving satisfying experiences in life. Because age is normatively related to how much life how much time we have left in life, as we grow older our emotion related goals increased importance and salience with age.

4. What is emotion regulation and why is it important to everyday life?

>> Well emotion regulation is the ability to handle situations well, to -- to dissipate the negative experiences to solve problems. So to that extent, good emotion regulation strategies are important for every facet of life, and particularly interpersonal situations.

5. How is emotion regulation learned? How do children regulate their emotions?

>> Well, what contributes to emotion regulation, at the basis, it's something that have very little control over, and that is our parents and our rearing environment. So when we are children, we have emotion regulation modeled for us, and we learn how to regulate our emotions by watching others and modeling their behavior. So we, we see how other people regulate their emotions and we learn how to do this, and I think that oftentimes people forget just how much humans are influenced by their environment, so it's very important to remain in situations where people are modeling good behavior for us, and also situations where we can regulate our emotions. So we have to know ourselves, and know our limitations, and understand the situations that where we will thrive, and those that are more difficult for us and are more demanding for us.

6. Besides age, what other characteristics contribute to healthy emotion regulation? How does environment influence the experience of emotion?

>> One aspect of emotional regulation where we learn how to regulate our emotions are through our environment and that begins when we are quite young and so how our parents and our caregivers shape how they perceive situations and how they respond and they react to their emotions teaches us how to respond as well and this shaping, although doesn't have as much of an impact when we're adults, we still are very influenced by our environment so it's important for us to understand our limitations, know that we're affected by those around us and to surround ourselves in healthy environments and also to understand the situations that are best for us so certain jobs and opportunities might be very challenging and motivating, for some people it might be very frightening or upsetting for others and so we need to know the environments that work well for our own personalities.

7. What factors can be observed in emotional processes across the adult lifespan?

>> Well my laboratory's been working on a theory looking at age related strengths in emotion regulation and also age related vulnerabilities.

8. Are there biological differences in the ways in which older and younger adults experience emotions? What strengths and vulnerabilities come with age?

>> So we're examining age related strengths in emotion regulatory in emotion regulation and what we find in many studies by out of my laboratory and many other people, that the thoughts and behaviors people employ to regulate their emotions, people are doing that more people are using these strategies more effectively or more often with age. So for example, older people attend to more positive and fewer negative aspects of their environment, their memories are less negative than those of younger adults and they praise situations by not thinking about the negative aspects and downplaying the negative situations so they are employing these skills to a greater extent than younger adults and we think they're doing that as a function of time, both time left in life as described by socio emotional selectivity theory, so they're motivated to use these strategies and they have they're able to use these strategies as result of time lived and their accumulated experiences with effective emotion regulation experiences so they can use these skills quite well. So we see these increase in cognitive behavioral strategies with age. At the same time, however, there are age related vulnerabilities and that is that physiologically people respond to emotions and so the best way to respond to a very highly distressful experience, the best way to respond physiologically is to quickly respond, stay at that high level until you effectively respond and engage in the necessary behaviors and then quickly return to your baseline experience so for older adults it takes them a lot longer to respond physiologically and then they stay aroused for a prolonged period of time relative to younger adults. So in situations where older adults are unable or cannot use the cognitive behavioral strategies to either avoid a situation or to keep it from creating these physiological response with the release of Cortisol and a very high levels of distress, in those situations we will not see age related improvements.

9. Does the reduction of social contacts as we age have emotional consequences?

>> Well the reduction of social context do have emotional consequences but not in the way most people expect. So many people find one of the most reliable findings in social gerontology in fact is the decrease in numbers of social partners as we grow older and so when people are watching the older adults are interacting with fewer and fewer people, the natural response is to recognize that social interaction is generally related to levels of depression and loneliness and so looking at these low levels, at one time people were understandably upset and wanted to increase social interaction for older adults, thinking that was the answer and that would make them less lonely and less repressed. Well, further research revealed, that older adults were not less lonely and more depressed than younger adults and Laura Carson said in her socioemotional selectivity theory flushed this out a lot more for us in science and what she and her colleagues found was that older adults were interacting with fewer social partners but this decrease in social partners were all the less close more peripheral contacts that people have on a daily basis. For interactions with close social partners and with family members, they were not seeing those age related increases in those partners and those partners are the most meaningful and satisfying partners for people arguably of all ages, although older adults do report higher levels of positive emotional experiences when with family members than the younger adults.

10. Can older adults experience growth in the area of emotion regulation, despite the traditional view that aging equals decline?

>> Well, I believe that emotions are one area that where positive psychology finds fertile ground, and it's one area of the optimist because despite very real declines in many processes with age, social losses, economic losses, loss in social prestige perhaps from retirement, physiological decline and health problems. So there, despite this array of loss, older people are doing very well in regulating their emotions. And so this is one area that we see a lot of stability across time. We do sometimes see decreases in positive affect in the very end of life, which is often when people control for functional limitations and health problems. We no longer see that decrease so it might be related to health declines or exposure of social loss such as bereavement, care giving stressors, physiological dysfunction. So we do see reasons for decline, but overall, it's a very positive picture.

11. Do we place more or less value on emotional experiences as we age?

>> There is a greater value based on emotional experiences, and that is from our motivation to, to derive meaning and, and attend to pos, to emotionally in the environment more so because we're motivated by our time left in life.

12. How do retirement and the absence of career-driven motivations affect the need for emotional experiences? Do we value different aspects of emotional life as we age?

>> Well, people's priorities do change with, with age, and there are studies using the term and data and other situations as well that look at the values people place on different aspects of their lives. And so at all times I think family and, and friendships are very important for people, but you do see waxing and waning of other, of other values. So, for example, when people are working, that is something that they place value on, many people, and when they retire, then you'll see, especially among men, the term and data. So an older cohort, but there you see once retirement occurs, men are placing more and more emphasis on their families.

13. What has surprised you the most in your research?

>> So concerning what, what surprised me when I first started examining emotional processes across the adult lifespan, what frankly surprised me was the, was not finding as many gender differences as I thought I would in memories or emotion or report of emotional experiences. So researchers do, certainly, find gender differences, in, for example, in, in depressive, levels of depression. Certain affective disorders we do, but I did not find a lot in my research. Now that the older I get and the more I, I do research, I, I'm less surprised by my findings, but I still am fascinated and very interested in what I find and what other laboratories are finding.

14. Why do you think few gender differences were seen in your research?

>> The reason why I think we do not find the gender differences that, at least I expected, is that people who study behavioral expression of emotion do, indeed, find gender differences. And what we might all expect because it does conform to our stereotypes, men are less expressive. So men do not express their emotions as much as women. And so perhaps I naively interpreted not expressing the emotion as not experiencing it in the same way, but what, what my research and other people have shown is that there's very few gender differences. So, so despite the fact that men are not expressing their emotions, they are feeling emotions very similarly in, in many, many of the experiences that I've assessed.

15. What direction do you see your research heading?

>> So, my -- the directions where, where my research is heading is that we, in my laboratory, are very interested in, in really pinpointing these age related strengths, and age related vulnerabilities and how these strengths and vulnerabilities integrate together to be able to predict where we will see age related benefits and where we will see age related declines in emotion regulation. And I'm particularly interested in particular environments and situations that allow the interrelated strengths to express themselves, as well as situations where they won't. And so, for example, when people are faced with, and bombarded with unrelenting stressors in their lives from functional disability and from caregiving stress, then we will not expect the same efficacy in the conduct behavioral strategies and we will see more declines related to physiological dis-regulation and that's what we're looking at in the lab right now.

16. How do you choose research participants?

>> Obtaining these participants is always a challenge, we want as representative a group as we can get, and so we do call them on the telephone, do interviews over the telephone, bring them into, into the laboratories, so we -- some studies are a questionnaire and you try to go to where they live or to where they will be, so we use a combination of strategies. Although it's, it's always a challenge, you, you want to get a very diverse group, and sometimes certain groups are much harder to find, so -- but we try to use as many strategies that we can think of."(Charles, 2013)

Memory and Memory Distortion: Elizabeth Loftus

Memory and Memory Distortion: Elizabeth Loftus

"1. How did you become interested in psychology?

>> Actually I was a math major, and I was taking a lot of math classes as an undergraduate. And then I needed electives, so I took Introductory Psyhology, and I just absolutely loved it. I -- I -- I can't even remember what it was about it that I liked, but it was so interesting, and it involved real people and real problems, and not just equations. And so I did all of my electives in psychology, and by the time I was done, I had enough credits to have a double major in mathematics and psychology. And I decided to go on in psychology.

2. What is your current area of research?

>>The work that I do is on memory and memory distortion, false memories. I deliberately distort people's memories in order to study the process by which that happens. And a lot of my most recent work is on planting entirely false memories into the minds of people, making people believe that they were lost for an extended time and frightened and crying and ultimately rescued and reunited with the family or making people believe that they met and shook hands with Bugs Bunny at Disneyland when that's impossible. And so, what I study is the process by which you can plant a little seed of memory and then watch it grow.

3. In what ways can memory be distorted, suggested, or totally implanted? Can you talk about your “Lost in the Mall” study regarding false memory?

>>What I was interested in is trying to plant an entirely false memory into the mind of someone for something that didn't happen. I wanted it to be something that would be upsetting, or at least mildly traumatic, if the event had really happened to someone. And at some point I stumbled upon the idea of why not try to make people believe that when they were five or six years old they were lost in a shopping mall or other big public place, that they were lost for an extended time, frightened, crying, and ultimately rescued and brought back together with their family. And the way we actually did it is to tell people we've been talking to your mother or your father or your older brother. We found out some things that happened to you when you were about five or six years old. And then we presented them with some true experiences, things the mother told us really did happen, and then this made up experience about being lost and frightened and crying and rescued. And when we were done with three suggestive interviews where we encouraged people to think about these experiences, the true ones and then the made up pseudo memory about being lost, by the time we were done we found about a quarter of our subjects fell for the suggestion and started to remember all or part of this getting lost experience. And that result was published in the 90's and now we and others have extended this and planted lots of different kinds of entirely false memories into the minds of people.

4. In what way do you address the ethics issues related to your research, as well as the concerns of your subjects?

>> Well of course we go through the human subjects committees and the human subject application process. Even in the name of science, of course, you don't want to do things you know will harm people so our studies are all approved by human subjects. And our debriefing is very carefully designed. I mean it depends on the specific study but during debriefing, you know, we like to tell people that we, you know, made up an experience and suggested it to them and we might, you know, tell them that there was a need for this kind of deception and try to make them feel their behavior is very normal. And you know for the most part, after planting false memories or false pieces of memory into the minds of probably 25,000 individuals in my career now, we've never had a single adverse effect so you know I don't see, I don't see a problem.

5. Have you followed up on subjects after memories have been implanted? Are they affected by true memories and false memories in different ways?

>> Our current work is looking at the consequences of having a false memory and so the way we're looking at this is to try to make people believe that they got sick as a child eating a particular food, like eating dill pickles or eating hard boiled eggs or eating strawberry ice cream or some particular food and then later we look and see if they avoid that food, if they have a tendency to not want to eat that food at a party or in a restaurant or what have you. And we find that these false memories do have consequences for people. And as far as we can tell, when we compare the true memories to the false memories, so you really did get sick eating eggs as a child versus I made you believe it and you now have a false memory about getting sick eating eggs as a child. There are very, very few differences between the true memory and the false memory in terms of their subsequent consequences.

6. What role does misinformation play in memory distortion? Is time a factor?

>> Well one of the most important factors for -- involved in the distortion of memory is exposure to some misinformation. So after you've had an experience, if I expose you to some misinformation about the experience -- if I feed you a version ostensibly told by another witness that contains erroneous information, or if I ask you suggestive and leading questions that insinuate the something different happened, we will frequently succumb to that misinformation, and adopt it as our own memory. And -- and then of course as time passes and the true memory gets weaker and weaker, it becomes even more vulnerable to contamination or distortion.

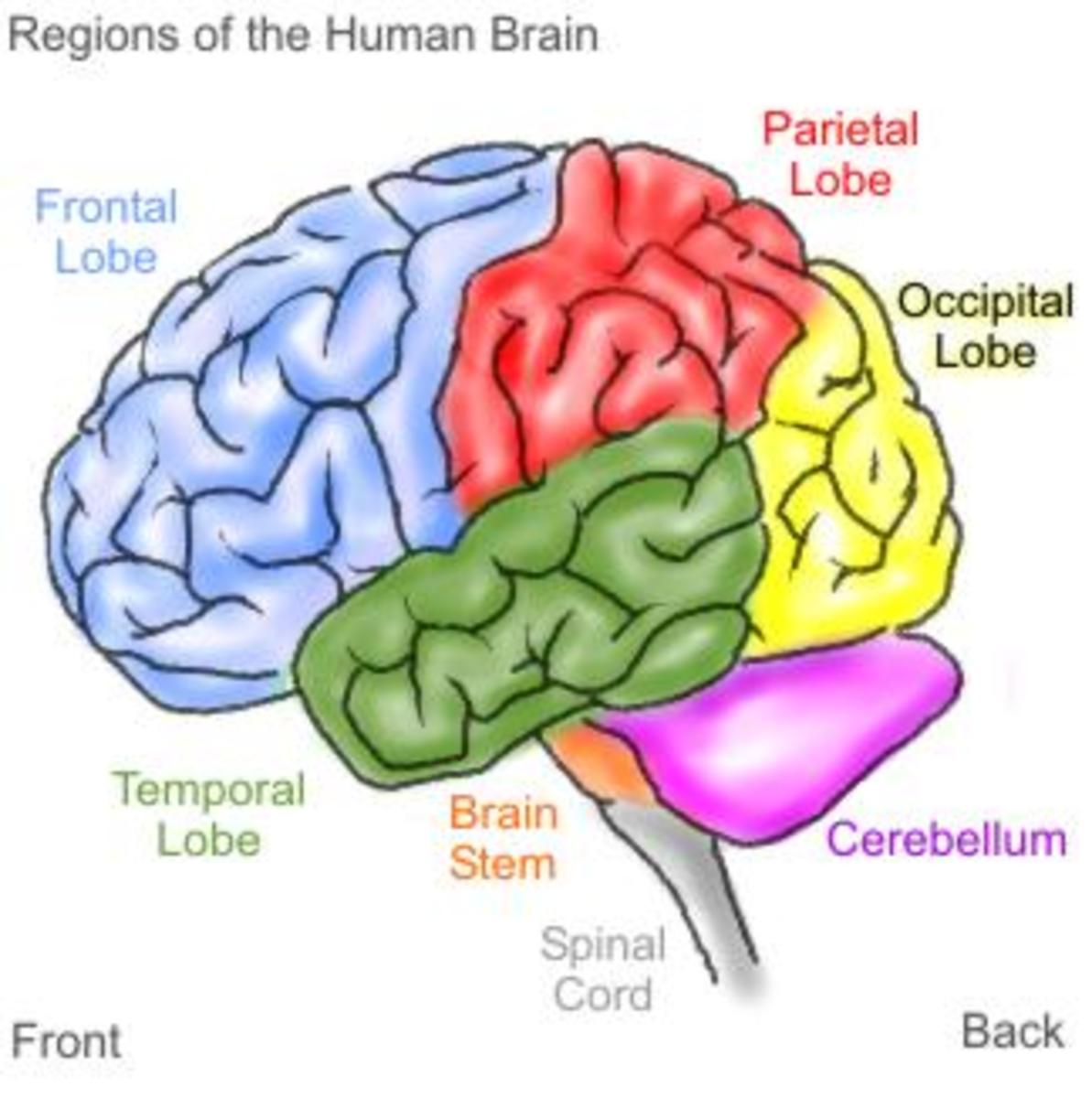

7. Does the brain perceive true and false memories the same way? What has neuroimaging found regarding distorted memories?

>> In some work that I have collaborated on, we have looked at neuro imaging, and sort of brain regions that might be active during the retrieval of something that did happen -- did truly happen in the past with true memory, versus the retrieval of something that didn't really happy but I've led you to believe that it did. And what surprises me about this work is that, you know, they're common areas of the brain that are -- are activated. Occasionally you can find some little differences, especially if -- if -- if the false information was suggested in an auditory way, whereas the original event was something that was actually seen -- visually seen. Then you might see a little bit of difference between a true memory and a false memory in terms of true memory's more activation in the visual cortex, and false memory's a little more activation in the auditory cortex. But, you know, I think the overwhelming impression from all of this neuro imaging work is just the -- the common areas of the brain that are active when you're experiencing something that truly happened versus something that didn't.

8. What happens to a person’s memory after a traumatic or upsetting experience? After a pleasant experience?

>> Well generally when something extremely upsetting happens to you, you, you know, you store information about it in -- in memory. But that information is like other kinds of information in memory -- it's subject to decay with the passage of time, it's potentially sub -- susceptible to contamination. So you can distort people's actual memories for a traumatic experience, just like you can distort their memories for non-traumatic experiences. I mean I think these -- these traumatic experiences and -- and more ordinary experiences, while some may be better remembered than others, they do obey certain laws of memory that are common in the two situations.

9. What are the laws of memory?

>> Well, so -- so for example, you know, the more times something happens, the better your memory for it. That -- that's kind of a law of memory. And that's true whether it's a -- a -- kind of a more mundane event, like, you know, taking a walk or -- or, you know, exercising in a particular way, or something that's more upsetting and arousing, and -- and even traumatic, that the more times something happens, the better your memory. The longer the time that's passed since the event, the worse your memory. The more you expose somebody to -- to contaminating information, the worse your memory.

10. Can you talk about some real-world applications of your research in the filed of criminal justice? For example, what is the role of memory in faulty testimony?

>> I think one of the most important applications of the work on memory and memory distortion is to the legal system. And we know now that -- that there are many people in prison who have been convicted of crimes that they didn't do. And as these cases are now coming to light, and we now have hundreds of them to analyze, so you can look at the case, and this person spent 5 years, 10 years, 15 years in prison for a crime that he didn't do, or she didn't do. And when -- when these cases are analyzed, the major cause of these wrongful convictions is faulty eyewitness memory. And so it behooves us to try and understand how -- how -- what -- what -- what can we learn about memory? And what can we learn about approaching witnesses, and getting information from them about their memories that will help reduce these errors? Because, you know, for -- for every innocent person who's sitting in prison, there's a guilty one still out on the street, you know, possibly -- probably committing more crimes. So I think that the work that I and other psychologists have done in the area of memory and eyewitness testimony has helped to refine some of the procedures that law enforcement use, or that investigators use with actual witnesses, and hopefully reduce the likelihood of wrongful convictions.

11. Which common police procedures were revised once it was understood that memory can be contaminated and distorted?

>>Well for example you know one important...one important issue is separating witnesses. When investigators approach witnesses and want to interview them about a crime for example, you separate those witnesses. Don't let them hear what each other says because they can be supplying information to each other and contaminating each other's memories. So it's now widely accepted that you separate witnesses and interview them separately so that you avoid this contamination. Asking non-leading questions to try to get information from the witnesses so you don't inadvertently supply information to the witnesses that might not be accurate. Conducting lineups to have somebody try to identify a person who might have committed a crime. How do you conduct those lineups? What instructions do you give people? And so we know from research that it's very important to give an instruction that essentially says, "You know the guilty person, you know the perpetrator, may or may not be in the lineup." It's just as important to free innocent people as it is to find the guilty party so don't feel pressure to identify someone. If the person isn't there, just say, "The person isn't there." And that kind of instruction is important to encourage people not to just pick the one who best fits. You only want to pick the person if you're pretty sure that that's the person who did it.

12. Can you discuss other real-life applications? What direction do you see your research heading?

>>Well, right now I am very interested in the consequences of false memories. So do false beliefs and false memories have repercussions for people? Do they affect later thoughts, later behaviors, and later intentions? And so we're now exploring different ways of studying the repercussions of having a false memory and one of the things that we're trying to do now is to plant a false memory. For example, you got sick eating a particular food. And then we want to see if people will actually avoid the food when real food possibilities are put in front of them. And you know, our first hint at this...at results were showing that people will avoid certain foods after they develop this false belief about having gotten sick and we think that we might be actually on the brink of a new dieting idea. If we can get people by planting a little mental taste aversion to avoid certain foods, maybe that might make a little bit of a dent in the obesity problem in our society.

13. Can you give another example of memory distortion regarding something seen or witnessed, and the role of misinformation in this process?

>> Well, one of the earliest studies of memory distortion that we did was to show people a simulated accident, where a car goes through an intersection that has maybe a stop sign at the intersection. And then we later suggest to people that what they saw was a yield sign at the intersection. And many of our subjects will later on tell us I remember seeing that yield sign. They succumb to the misinformation, and they don't recognize the stop sign any more, even if you show them the original scene that they actually saw. So that's an example of how misinformation can contaminate somebody's memory for something they've previously seen.

14. What research findings have surprised you most?

>> Well one of the things that surprised me I think is the resistance people have to these ideas. So we have you know we'll show that we can distort somebody's memory and they'll say well you know that's not planting a whole memory into someone and then so we'll plant a whole memory about getting lost for example and they'll say well that isn't a really traumatic experience and so we'll try to plant something that would be more traumatic. You know you broke a window and cut your hand for example and they'll say well maybe it really happened so then we try to plant something that would be impossible so that they can't say maybe it really happened and that's where we came up with the idea, let's try to make people believe that on a childhood trip to Disney they met and shook hands with Bugs Bunny and we actually got a number of people by exposing them to a doctored advertisement for Disney that included Bugs Bunny. We got a number of people telling us they remembered meeting Bugs at Disney. This is impossible because Bugs is a Warner Brothers character but many people fell for this suggestion and you know even then, even after getting people to have an impossible false memory there's still criticism, people just find it hard to accept the idea that our minds might be full of little bits of misinformation."(loftus, 2013).