Greek Mythology Quiz: Heroines

Goddesses, Wives, Furies and Maenads

Next up, the "Greek heroines" edition of my Greek mythology trivia quizzes!

This quiz may be tough: women of the ancient world, mythological or otherwise, don't get much press. So just enjoy, and don't worry if you don't know all the answers! After the quiz, I'll share "mini-myths" about these Greek heroines and uppity women.

Greek myth quiz: goddesses & heroines

view quiz statistics

The Three Virgin Goddesses

Wisdom, wild things, and the hearth

In ancient Greece, virginity was as rare as unicorns. Fathers arranged marriages for their daughters very young, using them to secure alliances. Only in heaven could three stubborn goddesses demand of Zeus and receive permission to remain virgins.

Athena's roles included "defender of cities," a symbolic reason for her to remain inviolate. She was a tomboy of a goddess, proficient in war as well as the more womanly art of weaving. Myths show her interacting with heroes, acting like "one of the guys." If she were a sexual being -- i.e. a woman -- men might not have imagined relating to her as friend or ally, let alone mentor.

Artemis was a holdout from pre-Greek times when she was a mother goddess, lady of beasts and the wild. Motherhood and "outside" were mutually exclusive in the classical Greek imagination, so Artemis became a virgin huntress. Paradoxically, she remained a protector of childbirth and children.

Hestia, goddess of home and hearth, is an odd case. You would think such a domestic goddess would be married. But again, she represents something that should be inviolate. The goddess of every household cannot have her own, separate household.

Right: gravestone of a maiden who died at puberty. The sculpture portrays her giving up her dolls to Artemis, a tearful ritual for all girls just before their weddings. (My own photo)

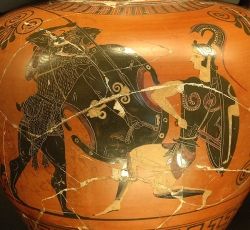

Atalanta, Follower of Artemis

The real warrior princess of Greek mythology

The Caladonian Boar Hunt is one of those blockbuster showdowns where all the big-name stars show up: heroes like Castor and Pollux, Theseus, and Peleus, father of Achilles. Wild boars were like rodeo bulls: huge, ferocious and powerful.

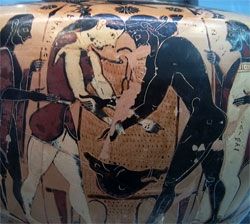

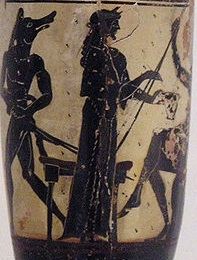

Among the hunters was one woman: Atalanta, exposed at birth by her father because he wanted a son, raised by a she-bear and later by Artemis. Her presence in the Caledonian Boar Hunt outraged the men. When she struck the first blow against the boar and won the right to its hide, conflict broke out. At right, an early Greek vase shows her wrestling with Peleus for the boar's skin (she won).

After the hunt, Atalanta's father discovered her and forced her to marry. She refused to wed any man who could not best her in a race. Many failed before one Melanion enlisted the aid of Aphrodite. The goddess gave him three golden apples to toss in front of Atalanta when she was ahead. By tricking her into stopping to pick them up, he defeated and "tamed" her.

Family Values vs. the State

The Tragedy of Antigone

The story of Antigone dramatizes the clash between old, pre-polis values, when family came first, and the new law-based civil system in which the state was more important.

Antigone's brother Polynices took up arms against Thebes, trying to depose his brother. Both were slain. Afterwards, their great-uncle Creon became king and declared that traitors should remain unburied.

Antigone defied the edict, buried her brother and was caught. Sophocles' famous play Antigone portrays the heroine defiantly preaching family loyalty above law in a fierce debate with Creon. She is sentenced to death. Creon's own son, Haemon, loves her and pleads her case, to no avail. They meet a rather Romeo-and-Juliet ending, committing suicide in the cave where Creon condemns her to be buried alive.

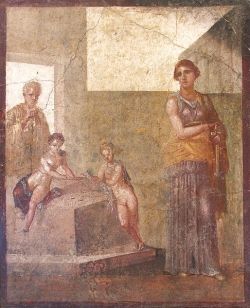

A Mother's Revenge

"Klytemnestra took an axe / gave her husband 40 whacks / When she saw what she had done / She gave Kassandra 41"

So runs a classics geek parody of Lizzie Borden's famous ditty.

In Aeschylus' gripping tragedy Agamemnon, the first extant play in history, Klytemnestra welcomes home her husband from the Trojan war with false flattery and a bath, then kills him. She was avenging her daughter Iphigenia, whom Agamemnon had lured to what she thought was her wedding, then sacrificed to the gods to win fair winds for the voyage to Troy. Klytemnestra also kills Agamemnon's unlucky concubine, Kassandra.

In variants of the myth, the murderer was Aigisthos, a rival of Agamemnon whom Klytemnestra had taken as a lover to spite her husband.

(Above, my photo of the "Mask of Agamemnon," buried with unknown noble at Mycenae.)

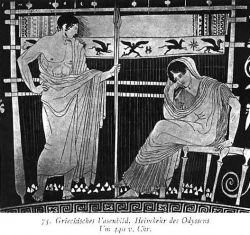

Queen of Ithaka, a Very Clever Wife

Penelope, wife of Odysseus

In contrast to Klytemnestra, Penelope stayed loyal to her husband Odysseus, even though it took him twenty years to return home from Troy.

Long after everyone was convinced he was dead, she fended off rich suitors with her wiles. She could not put them off forever without fear of one of them claiming her, so instead she promised to marry one of them as soon as she finished weaving a shroud for her aged father. The catch: each night she would unravel the fabric she had woven that day.

Eventually they caught on, but Odysseus returned home in the nick of time to dispatch them. Penelope was delighted, but wary: was this really the man she had said farewell to twenty years ago as a young bride? Therefore she played a trick on her trickster husband, testing him with a secret only he could know, to make sure he was not an impostor.

Jilted Heroine Has the Last Laugh

Ariadne, daughter of King Minos

Theseus, dashing prince of Athens, came to Krete to put an end to a gory practice. Since they had slain his son, King Minos exacted a tribute of youths and maidens from Athens who were sacrificed to the Minotaur, a bizarre monster that was half-bull, half-man. Things looked bleak for Theseus until he caught the eye of Ariadne the king's daughter, who smuggled him a sword and a spool of yarn so he could kill the beast and find his way out of the maze which served as its cage.

Theseus promised to marry Ariadne, and the lovers escaped by ship. However, Theseus abandoned her on the remote island of Naxos halfway home. Luckily for Ariadne, she was rescued by the god Dionysos, who made her his wife and queen and set her crown among the stars.

In fact the myth of Ariadne and Dionysos predates that of Theseus and Ariadne. She seems to have been one of several heroines like Helen and Medea who started their careers as local goddesses and were later "demoted" in classical Greek mythology.

How to Make a Dramatic Exit

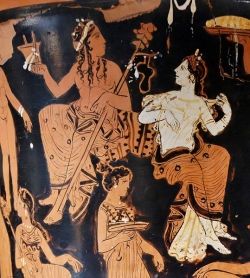

A chariot drawn by dragons -- now that's stylin'

Speaking of Medea, this ferocious lady was another jilted princess. In fact, like Ariadne, she was a granddaughter of the sun-god Helios. In the classical version of her myth, the rather timid hero Jason seduces her to help him on his quest for the Golden Fleece. Her father the king had set a ferocious dragon to guard the prize. Medea sedates the dragon with magic and helps Jason through many other trials as well.

Her reward? Once back home, he finds her a political embarrassment, and ditches her to marry another king's daughter. Medea sends a poisoned robe to the bride (killing off Antigone's nemesis Creon, by the way, who was the bride's father). Murdering her sons by Jason before his horrified eyes -- they would have been killed anyway as bastards and a threat to the throne -- Medea steps into a chariot drawn by dragons (or serpents) and flies up to heaven.

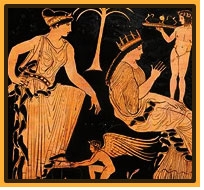

We have a good idea what this show-stopping special effects moment looked like at the end of Euripides' play Medea, because several vase painters painted nearly identical images of Medea in her chariot. (Greek theater employed a crane.)

Queen of the Amazons, Hippolyta

Why steal her girdle?

Myths about Queen Hippolyta vary, but they agree on two points: Herakles comes to steal her girdle, and it was not originally a girdle! Her zoster was a warrior's belt, given to her by her father Ares as a symbol of power. In most versions of the myth, Herakles kills Hippolyta after stealing the zoster.

Herakles was only the last of Hippolyta's troubles. Athenian legend says that Theseus abducted Queen Hippolyta (named Antiope in the earliest versions of the tale) and married her. The Amazons make war on Athens but fail to rescue her. This Amazonomachy, the "war with the Amazons," is a popular motif in Athenian art, symbolizing Greek triumph over barbarism.

Different ancient writers say that Hippolyta died in that battle, died leading the Amazons against Theseus after he put her aside to marry yet another princess (Phaidra, Ariadne's sister), or died after returning home only to run into Herakles.

And yes, this is the same Hippolyta who marries "Duke Theseus" in Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream. Old myths never die; they just get new movie adaptations.

Circe / Kirke, daughter of Helios the sun-god

Odysseus' favorite stopover on his voyage home

Kirke (the Greek spelling of her name) is yet another old goddess who was absorbed by later Greek mythology, but she seems not to have lost much of her power. Note that classical myth makes her the daughter rather than the granddaughter (Ariadne, Medea) of Helios.

Homer spends a couple books on Odysseus' adventures with the witch Kirke. She transforms all visitors to her island into animalst Wily Odysseus thwarts her with the help of Hermes, who gives him a magical flower that renders him immune to the witch's magic.

Kirke then takes Odysseus as lover for a year. She sends him off with good advice to help him navigate the next few perils of his voyage. Many myths say she had a son by Odysseus, Telegonos, who in some myths accidentally kills his father and/or marries Penelope.

Kassandra (Cassandra) of Troy

Don't listen to me; nobody else does

Kassandra, daughter of King Priam of Troy, was so beautiful that Apollo gifted her with the power to know the future. When she refused his advances, he punished her. He could not retract the gift, so he added a nasty curse: no one would believe her.

She knew Troy was doomed. She warned her people about Helen, about the Trojan horse. It never helped. During the sack of Troy, Ajax dragged her from the temple of Athena (right) and violated her. He got his comeuppance; Athena killed him. Alas, that did not save Kassandra. She became the slave of King Agamemnon, taken to his palace in Mycenae. There, according to Aeschylus' Agamemnon, she was murdered.

Her speeches in that play are powerful and chilling, especially if you know Greek: Ἄπολλον, ἀπόλλων ἐμός "Apollo my destroyer," is her title for the usually beneficent god. She goes to her death with head held high in this, the first surviving play in the western world.

Women's Lives in Ancient Greece

So, What Was It Like, Anyway?

While women in Sparta had some control over the lives and property, most Greek women were under the control of male guardians: first their father, then their husbands. The guardian arranged their marriage. They were married at puberty; men married in their thirties.

Women were kept upstairs or in the back of the house, and were permitted outside only for religious festivals or funerals. Female slaves and prostitutes could be seen in public, but of course led hard lives. A few free-born women, priestesses of state religious cults, might participate in public life in a religious capacity and wield some respect.

Most women received no education beyond domestic arts like weaving. This coupled with the age disparity between child bride and husband meant that women were looked down upon as passive, flighty, ignorant, emotional, and unable to care for themselves without a man in charge.

Why, then, are there strong female characters in myth? Some are fantasies (the ancient equivalent of Lara Croft and Xena) or expressions of men's fears. Others are echoes of Bronze Age Greek myths, when women apparently had more autonomy. Finally, goddesses are not like flesh-and-blood women, any more than America's Lady Liberty represented the situation of real American women barred from voting until 1920.

Amazon Spotlight: Uppity Women of Ancient Times

© 2009 Ellen Brundige