In This Corner: The U.S. Dollar VS The Chinese Yuan

In order to be a world dominant economy again: an economy that stands above and beyond all the rest. The United States will need to repaint its aging green dollars with a new vibrant emerald color—aka, the refurbished emerald green dollar bill if it wants to take a page out of its old "big book" may be forced to read excerpts from a new kind of currency tome written thus far in mandarin. The very idea that the Chinese yuan or renminibi (RMB) cannot be used as a reserve currency has slowly been falling. What’s been rising in its inverse is the very notion that the yuan can, indeed, become a dominant international currency, thereby divorcing its “pegged ties” with a rusty ‘ole green dollar bill that doesn’t seem to know if it’s going or coming.

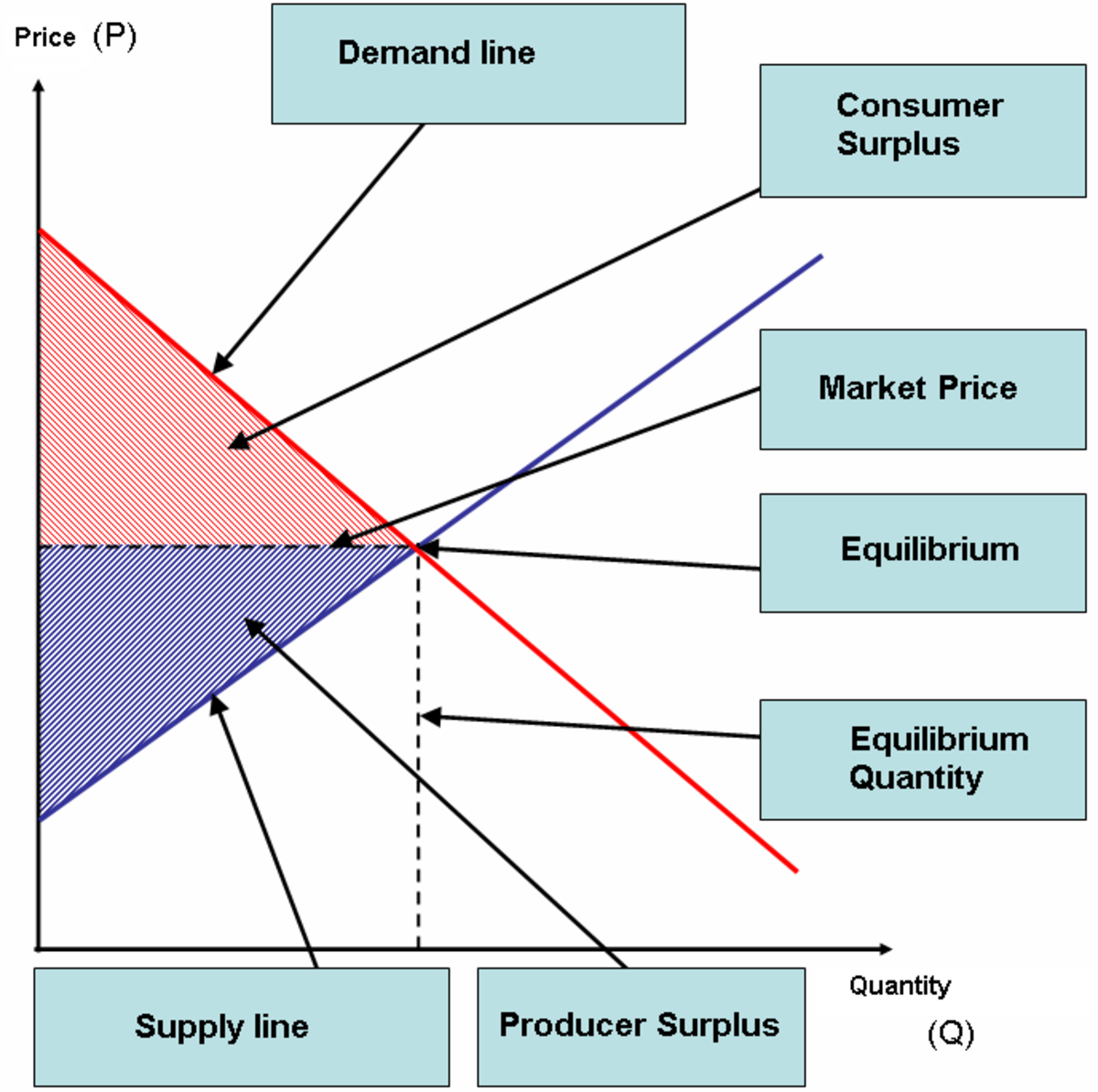

What’s causing the US dollar’s uncertainty? A better question might be: “What ever happen to the strong dollar bill of yesteryear?” Anyone with basic economic knowledge can postulate what may have happen, but the fact remains is that the US threw away all conventional wisdom in reference to its strong dollar when it adopted a full scale flexible exchange rate system, which essentially mandates central banks to meddle in the exchange rate market affairs. So much for all this meddling...when you got two powerhouse currencies “duking it out" like the US dollar and the Chinese yuan, the one with the better overall economy usually stands be the winner.

Still, as it is today China’s manufacturing stands in a league of its own. This shouldn’t be that much of a surprise anymore given the Chinese remarkable penchant for producing remarkably price manufactured goods at both a competitively domestic and international level—much of which can be attributed to China’s state capitalism. Unlike the US central bank, the Chinese central bank acts as China’s sole mono-bank, thus undertaking both commercial and central banking roles—two roles China relishes to the point of maintaining hermetic capital controls on the exchange of its currency. What China’s doing isn’t too hard to understand: when you got two currencies battling for economic supremacy, the Chinese government may be tacitly telling its young & mighty yuan to take a dive for the betterment of its state run enterprises—i.e, its massive manufacturing sector thus the massive current account surplus that goes along with it. A weak yuan lowers the cost of producing manufactured goods in China, thus making exports more competitive overseas.

When you put it in those terms, the dollar wins, but it loses: whether it’s time to be happy or sad for the ‘ole green back isn’t the prevailing issue. What seems to be on most Americans minds is the future prospect of an uncertain currency and of course, how do we restore the dollar to its prime green color? All this talk of the dollar’s demise and doomsday type scenarios which sirens an possible crash of the greenback has got many thinking whether the U.S. should go 'ol skool--i.e., bring back a fixed/adjusted system similar to Bretton Woods.

This may sound crazy, but if the Chinese adopts a similar type system as Bretton Woods, thereby backing its yuan with some kind of commodity (copper, silver, gold, oil, coal, whatever), the American dollar would be rendered worthless overnight. It would be analogous to the US throwing in the white towel. The advantages of a Bretton Woods type system speak for itself:

Macroeconomic performance was highly notable—as the rate of inflation was kept at bay on average and for most industrialized nations.

The degree of exchange rate stability compared favorably with volatility of preceding and subsequent period.

Unprecedented expansion of international trade and of investment occurred during the Bretton Woods years.

Because our currency was backed by something other than the “word” of the federal government, the dollar had real value.

Simply put, you have to back "paper money" with something within the earth and of high demand. For example, the small oil rich country of Kuwait implicitly backs it’s dinar (the strongest currencies in the world) with its vast oil reserves. As I write this hub it takes close 3.6 dollars to get 1 Kuwait dinar. What’s making the dinar so strong? Well, it’s simple, the dinar is backed by the very strong oil based Kuwait economy...oil, of course, being a commodity and something that’s found within the earth.

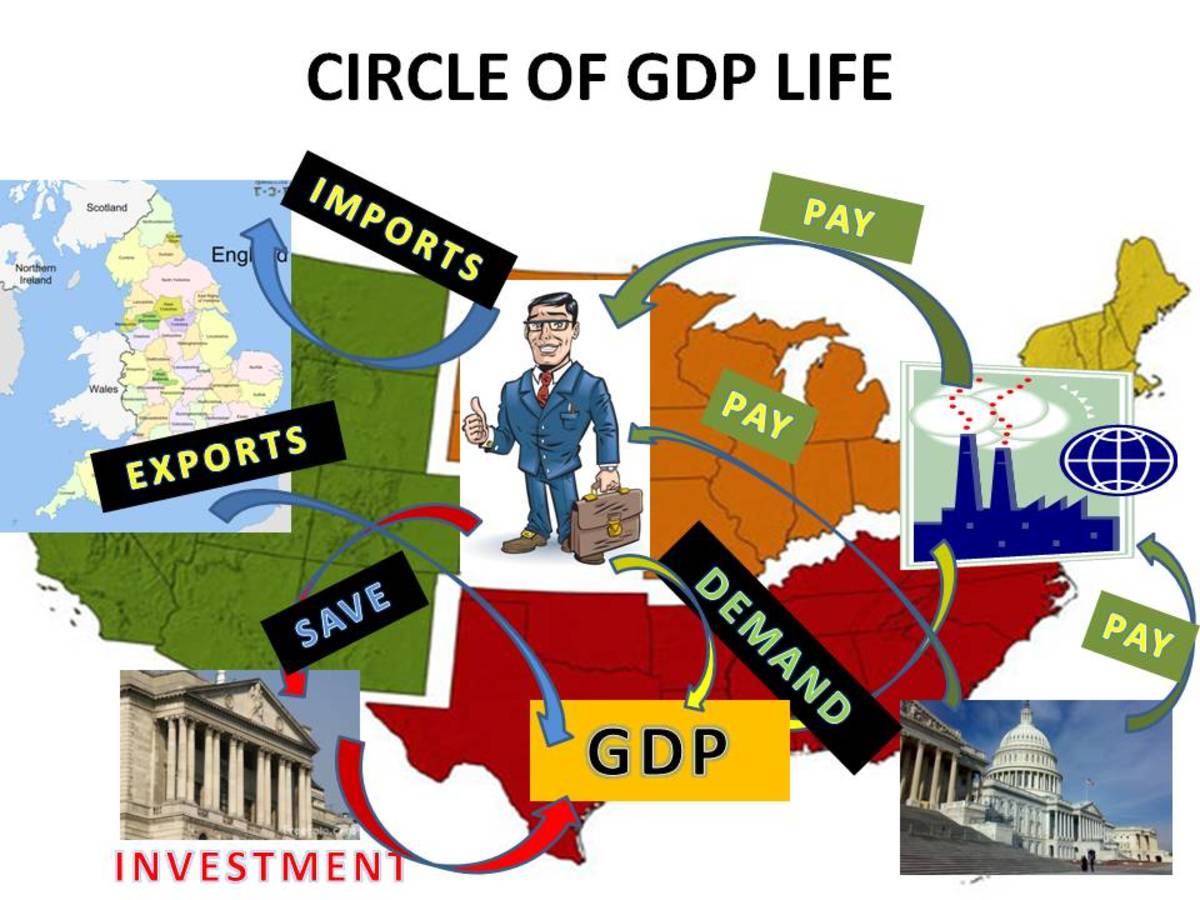

By doing a Bretton Woods style monetary system, just like Kuwait with the dinar, we’ll be creating a very strong currency. What does a strong currency say about an economy? A strong currency says a lot about an economy: it says, among other things, that an economy is steadily growing, it has a relatively stable investment environment and it’s economically sufficient. Everyone knows that in economics there exist “trade offs.” The trade off of a strong currency is “higher prices” for imported goods. It also vastly increases the cost for American tourists traveling abroad. Who wants that? Because the United States currently has an enormous trade deficit (importing more than it exports) this represents a significant drag on efforts to spur vital economic growth to our economic engine. A growing economy needs jobs creation, productivity, etc.

This said, if we want to keep our currency from weakening any further, we need to strive to repay this massive foreign debt. History has shown, any economy that wants to stay competitive in a sluggish environment has to strive to maintain a strong currency. Just look at the Brazilian real and how it has taken off under the Lula administration. A strong economy begets a strong currency and vice verse: the extraordinary growth on the part of the real is coming from a nation that has seen its fair share of macroeconomic upheaval. Brazil’s economy in the decade of the early 90s experienced hyperinflation that rivaled Germany’s Weimar Republic of the 1920s. Again, the Lula administration built a strong robust economy and the real calibrated for those changes.

Let’s not forget about China and how its yuan’s slowly becoming what the U.S. dollar used to be. If the Chinese central bank backs its yuan with some kind of commodity, the yuan will instantly become the “de facto reserve currency” rendering the U.S. dollar on the international scale a moot point. Part of America’s problem is pure hubris: we don’t believe that our economy can take a back seat to other economies and history has shown that’s not always the case. Just look at how our banks failed us in 2008; look how our monetary system isn’t up to par with its full potential. It’s like having a big strong punching prize fighter with bad trainers: the boxer feels that he can train himself without the help of his corner. But in reality, all good fighters need good corners. Our government thinks that our economy is just “too big too fail” economic history proves that they could be wrong.