- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Major Inventions & Discoveries

Who Invented the Lawnmower?

Nowadays considered an indispensable tool for the maintenance of a suburban backyard, the lawnmower is something we tend to take for granted. Before its invention, however, lawns had to be laboriously trimmed by hand with shears or scythes.

The traditional lawnmower consists of a set of curved blades arranged between two wheels. When the operator pushes the long-handled machine, the wheels turn and connecting gears cause the blades to rotate at high speed. The contact of the blades with the ground shears off the individual stalks of grass.

History of the Lawnmower

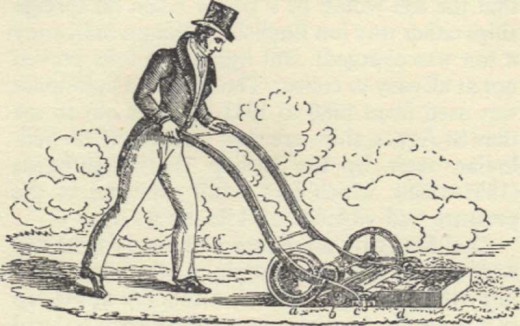

The Lawnmower was invented by Edwin Budding, an engineer in the cloth factory of a Mr Lister of Stroud, in Gloucestershire. In the year 1830 Budding patented 'a machine for cropping or shearing the vegetable Surface of Lawns, Grass-plots, etc.' He derived his idea from a small device made for cutting the pile on cloth; and he used to practice with his first lawn-mower, in its earliest imperfection, on his own back lawn after dark - to the great mystification of his neighbours.

The first mature lawnmower was manufactured to Budding's specification early in 1831 by John Ferrabee at his Phoenix Foundry near Stroud, and before the end of the next year similar machines were being produced by James Ransome of Ipswich. Twenty years later Messrs Ferrabee and Messrs Ransome showed the only two lawnmowers at the Great Exhibition. They were almost identical with the original; and indeed the earliest mowers were very similar to our present-day machines.

Budding himself was delighted with his invention. 'Country Gentlemen', he says, 'may find, in using my machine themselves, an amusing, useful, and healthy exercise.' But the machines were made in two sizes, and a correspondent of the gardening author John Claudius Loudon wrote in September 1831, 'I have had one of Budding's machines in use, when the grass required it, all this year, and am highly pleased with it. The narrow machine is best for a gentleman who wishes to use it himself, but the wide ones are preferable for workmen.' The small mower cost seven guineas, the larger one ten; and Loudon, who was a gardener with a disinterested passion for progress, expressed the 'sincere hope that every gardener whose employer could afford it would procure a machine and give it a trial'.

Most of those who took Loudon's advice were well satisfied. Mr Curtis, head gardener at the London Zoo, calculated that 'with two men, one to draw and another to push, the new mower did as much work as six men with scythes and brooms'. And it was, of course, by scythe and broom that lawns had hitherto been kept in their English perfection. It used to be a tedious business, and Loudon had, years before, worked out with mathematical precision the most economical method of cutting and clearing a large lawn - so that in the end the area was 'studded with heaps of grass sixty feet apart one way, and fifteen or eighteen feet apart the other way'. These heaps were then 'basketed into the grass-cart by a man and a boy with a couple of boards and a besom'. Under the old system any man with enough practice could become a good mower of lawns. It was the tidying up that was the trouble. But in spite of the obvious advantages of the machine with its grass-box, there was for long among gardeners a conservative party who persisted in the use of the scythe; and down, at any rate, to the Second World War there were many aged men in Great Britain who retained the old skill and could scythe a grass plot perfectly smoothly to the eye and softly to the tread.

The tide finally turned, however, with the coming of Lawn Tennis in the seventies. By then horse-drawn mowers were in use at Kew; and Dean Hole tells of a gardener at Rochester Asylum who used to harness seven madmen to his machine. In the early eighties a Mr R. Kirkham devised a mower propelled by a pedal-driven tricycle, but this never became popular. Rather more successful, but not much more, was Mr Summer's one-and-a-half ton steam-driven mower, patented in 1893. Any future that this last monster might have had was prevented by the perfecting of the internal-combustion engine. In the present century the motor-mower has made the keeping of lawns so simple a matter that in 1939 it was calculated that lawn grass covered more than seventy-five per cent of the total garden area of England.

Edwin Budding's name does not occur in the Dictionary of National Biography, nor has any public memorial been put up to him or statues to celebrate his contribution to society, but everywhere where lawns flourish, gardeners are immeasurably in his debt.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2009 Bits-n-Pieces