- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Endangered Species

The Tragic Loss of The Great Auk

Introduction

Imagine a penguin gliding through the chilly waters of the North Atlantic while standing in Iceland, Newfoundland, or the coast of Scotland. This wasn’t a wayward Antarctic traveler. It was the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), a large, flightless seabird once so common that fishermen and explorers could fill boats with them in a single trip.

By the mid-1800s, they were gone forever. Hunted relentlessly for meat, feathers, and eggs, the Great Auk vanished from the Earth in a heartbreaking example of how quickly human activity can erase an entire species.

Yet, their story isn’t just about loss — it’s also about what we might learn, and even what science might one day restore.

What Was the Great Auk?

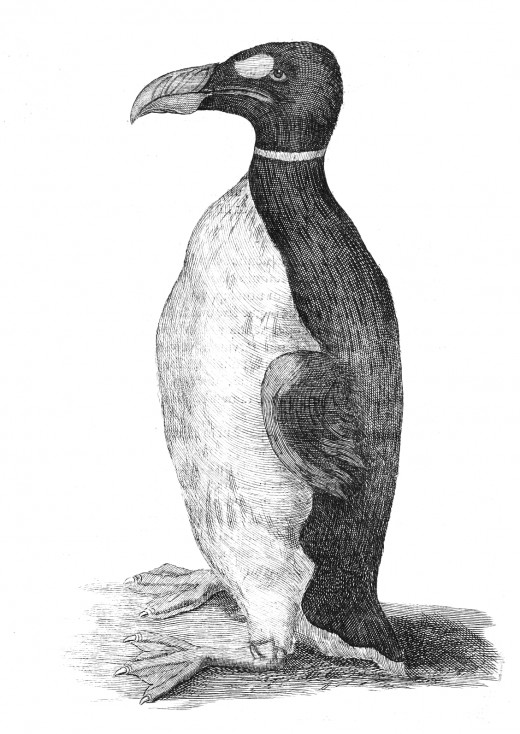

The Great Auk was the largest member of the alcid family — a group that includes puffins, razorbills, and murres. Standing about 30 inches tall and weighing up to 11 pounds, it was built for life in cold northern seas. Its sleek black-and-white plumage, short wings, and upright posture made it look uncannily like a penguin, even though the two aren’t closely related.

Unlike penguins, the Great Auk lived entirely in the Northern Hemisphere, breeding on remote rocky islands in the North Atlantic. Their small wings were useless for flying, but perfectly adapted for swimming, allowing them to dive deep in pursuit of fish and crustaceans. On land, they moved clumsily — a fact that would prove their undoing.

For centuries, the Great Auk thrived in vast colonies. But its trusting nature and inability to fly made it one of the easiest animals for humans to capture — a vulnerability that would eventually seal its fate.

The only known illustration of a Great Auk drawn from life

Life in the North Atlantic

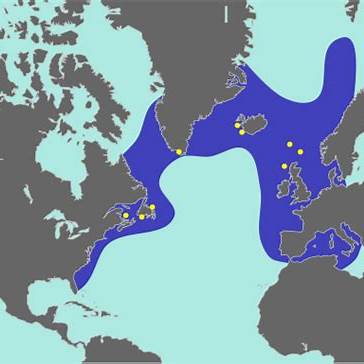

The Great Auk was a true creature of the cold ocean. Its breeding colonies dotted windswept, rocky islands far from predators — places like Funk Island off Newfoundland, the skerries near Iceland, and the remote coasts of Scotland and Ireland.

During the breeding season, thousands of birds crowded together, their raucous calls echoing over the cliffs. Pairs would mate for life, returning to the same spot year after year to lay a single, large, speckled egg. These eggs were strikingly beautiful — creamy white with bold brown markings — and each was unique enough to be identified by its owner. Unfortunately for these sea bird, when nesting on land they were vulnerable. Although they are fast and agile swimmers, on land they are slow waddlers with no real means of self defense. This, combined with the fact that a breeding pair could only raise a couple young per season, made them vulnerable to predators.

Outside of breeding months, Great Auks were at sea, swimming vast distances to feed. They were expert divers, capable of chasing fish underwater for extended periods. Their presence was so familiar to sailors that spotting them was once a sign you were nearing northern shores.

Historical Range and Nesting Sites of the Great Auk

The Road to Extinction

The Great Auk’s decline began far earlier than most people realize. Fossil evidence and early historical accounts suggest that these birds once bred along the coasts of northern Britain, including Scotland and the Orkney and Shetland Islands. However, by the Middle Ages, they had already vanished from much of Europe — likely the result of overhunting by early humans who prized them for meat, eggs, and feathers.

With their numbers shrinking, the surviving Great Auks retreated to the most remote and inhospitable islands of the North Atlantic — places so windswept and wave-battered that humans rarely set foot there. For centuries, these rocky outposts served as their last refuges, from Funk Island off Newfoundland to Eldey Island in Iceland.

But isolation couldn’t protect them forever. By the 16th century, European sailors and fishermen had discovered these final breeding grounds. On land, the birds’ slow waddle and inability to fly made them easy prey. At sea, hunters could drive them toward shore and capture them in large numbers.

They were killed for their meat, which could be salted for long voyages; their feathers, used to stuff bedding; and their fat, rendered into oil. Egg collecting became another blow — each Great Auk laid only one large egg a year, and removing it often meant killing the adult birds as well.

By the 1800s, the Great Auk had vanished from almost all its breeding sites. The few survivors became highly sought-after trophies for private collectors and museums, sealing the species’ fate.

Modern photo of Eldey Island, where the last confirmed Great Auks were killed.

The Final Days

By the early 1840s, the Great Auk was teetering on the brink of extinction. Only a handful of breeding pairs remained, most on a single isolated rock in the North Atlantic — Eldey Island, off the coast of Iceland. Sadly, at this time, "preservation efforts" often mean collecting "samples" for museums. The scarcity of these birds put a price so high on their heads that sailors could be paid more for a single bird, then they earned the rest of the year fishing.

On June 3, 1844, three Icelandic men landed on Eldey with orders from a collector to obtain Great Auk specimens. They found a lone pair nesting on the bare rock, guarding their single egg. In a grim scene recorded later, the men killed the adult birds by clubbing them and accidentally crushed the egg underfoot. Those two birds were the last confirmed breeding pair ever seen alive.

A few unverified sightings followed in the 1850s, but no solid evidence emerged. The Great Auk — once so common it was called “the penguin of the north” — had vanished completely, another victim of human exploitation.

Today, about 80 mounted specimens exist in museums worldwide, along with a scattering of eggs and preserved body parts. These relics are the only tangible link to a bird that once filled the seas of the North Atlantic.

One of the Specimens in Museums around the World

Lessons from the Great Auk’s Extinction

The Great Auk’s disappearance is more than a sad footnote in history — it’s a warning. Their extinction shows how quickly human activity can overwhelm even abundant species, especially those with slow reproduction and limited defenses.

They were not wiped out by natural disaster or gradual climate change. They were lost because humans hunted them faster than they could breed, destroyed their nesting sites, and turned them into commodities.

Today, many other species — from seabirds like the Atlantic puffin to large mammals like the polar bear — face similar threats from overfishing, habitat loss, and climate change. The Great Auk’s story reminds us that extinction is permanent and that conservation efforts must begin before a species reaches the brink.

Remains of the Great Auk in a Museum

Could the Great Auk Return?

It might sound like science fiction, but researchers are exploring the possibility of bringing the Great Auk back through de-extinction. Advances in genetic technology — including the same methods a major genetic company (Colossal Biosciences Inc.) is using to revive the Dire Wolf — could, in theory, recreate the Great Auk by inserting its DNA into the eggs of a closely related living bird, such as the razorbill.

However, even if science succeeds in producing a living Great Auk, major challenges remain. Their historic breeding islands would need protection and restoration. The ocean conditions that once supported their vast numbers have changed. And scientists continue to debate the ethics of reviving extinct species — should we focus on bringing them back, or on saving the many species currently at risk?

Whether or not the Great Auk ever returns, its story has already given us a clear message: we hold the power to either destroy or protect the life around us. The choice is ours.

Learn More about the Tragic Discovery of Extinction of the Great Auk

If science could bring back the Great Auk, should we do it?

Conclusion

The Great Auk’s tale is one of abundance turned to absence. For centuries, these remarkable seabirds thrived across the cold northern seas, shaping ecosystems and inspiring sailors’ stories. Yet within a few human lifetimes, they were gone — not because of nature’s cruelty, but because of our own.

Today, as we face a new wave of extinctions, the Great Auk stands as a silent witness to the urgency of conservation. Whether science one day brings it back, or whether it remains only in memory, its story challenges us to protect the species that still share our planet.

We may never walk the cliffs alongside the Great Auk again, but we can decide that no other creature will vanish the way it did.

© 2025 Christopher Gargan