Suicide rates and suicide risk factors

Introduction

Suicide is the ultimate self-destructive act. An action that is virtually unknown in other animal species, a human being taking his own life is an event that invariably causes devastation to the surviving loved ones.

In the USA around 38,000 people commit suicide each year; one person every 14 minutes. The United Kingdom has a similar suicide rate (about 12 per 100,000 population) with around 6,000 people aged 15 and over killing themselves in 2011, the most recent year for which official figures are available.

Although these levels of self-destruction seem disturbingly high, they are without doubt significant under-estimates. Suicide is a legal verdict and coroners are reluctant to draw this conclusion unless there is unequivocal evidence to support it, being mindful of the detrimental impact a suicide verdict might have on relatives, both emotionally and economically – life assurance policies tend not to pay out following a suicide. To illustrate, what this means in practice is that if a person hangs himself and leaves a suicide-note the verdict will be suicide; if someone has been expressing unhappiness and later drowns in a river the likelihood is that a different verdict will be reached.

Many myths are associated with suicide. What follows are 9 snippets of information, all supported by the research evidence, that are intended to promote a better understanding of the subject.

More males than females commit suicide

Men are 3- to 4-times more likely to kill themselves than women. In the USA the 45 to 54 age group had the highest suicide rate, whereas in the UK it was men aged 30 to 44.

With regards to sub-lethal deliberate self-harm (variously referred to as parasuicide, attempted suicide, failed suicide or self-mutilation) women outnumber men by a ratio of about 3-to-1.

Deliberate self-harm is a risk factor for future suicide

People who regularly engage in deliberate self-harm, such as drug-overdose or self-mutilation, may do so for a variety of reasons. For example, some people display such self-loathing that they harm themselves as a form of self-punishment whereas others may cut themselves as a way of regulating overwhelming emotional pain. Thus, sub-lethal self-harm is often not a failed suicide attempt but, instead, fulfils a number of other functions.

As such, mental health professionals frequently view the deliberate self-harm and suicide groups as being distinct populations. Although there are clear differences between self-harmers and suicide-completers, there is also significant overlap. For example, deliberate self-harm is one of the strongest predictors of future suicide. People who deliberately self-harm have a 1% chance of killing themselves in the subsequent 12-month period. Although this figure might not sound particularly striking, it represents a 100-fold increase on the risk of suicide for the general population.

The most common reason for taking a deliberate drug-overdose is, "I felt so desperate I didn't know what else to do."

Most of the people who present to Emergency Rooms/Accident & Emergency Departments after deliberate self-harm have taken drug-overdoses. The reasons for doing so are many and varied, and most people who ingest drug overdoses do not have a desire to die as their primary motive.

A number of research studies have asked drug-overdose patients, while they recover in a hospital bed, to pick from a list of possible reasons that underpinned their actions. The consistent finding is that the most frequently endorsed reason is, “I felt so desperate I didn’t know what else to do,” suggesting a perceived lack of less destructive alternatives.

Suicidal people are often poor at solving interpersonal problems

Research has shown that suicidal people are less effective at solving interpersonal problems than equally depressed, non-suicidal people.

To illustrate the difference between an effective problem-solver and an ineffective one, consider a man who has moved into a new neighbourhood, does not know anybody but wants to make friends. How should he go about it? A good problem-solver would be able to generate a range of specific and proactive ways of increasing the chances of forming friendships, for example: throwing a house-warming party; going for a drink in the local pub; taking the dog for a walk and striking up conversations with other dog-walkers; and knocking on the neighbour’s door to introduce himself. A poor problem-solver would struggle to generate potential solutions, instead relying on passive strategies such as “wait and see what develops.”

Difficulties resolving interpersonal problems may elevate the suicide risk, as life’s challenges are more likely to be viewed as insoluble with death being perceived as the only available solution.

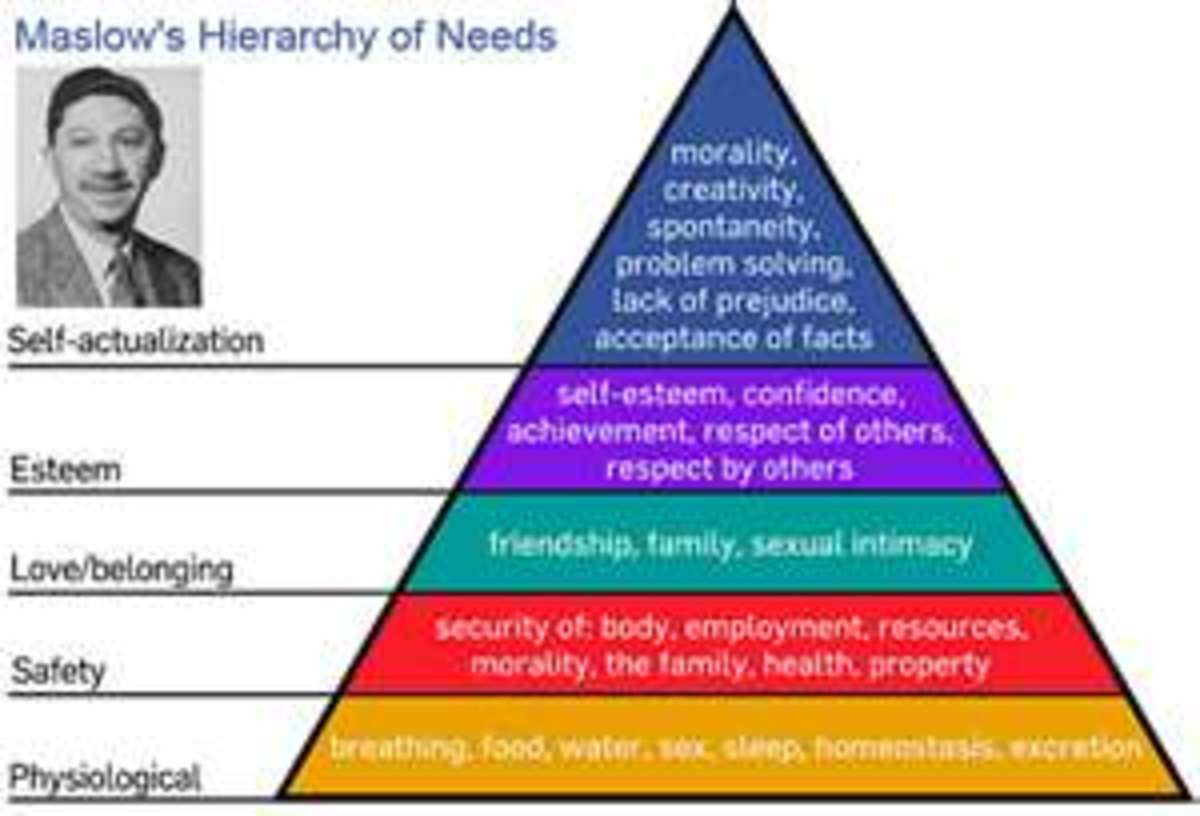

Hopelessness is a strong predictor of suicide

Suicide risk increases as hope for a better future diminishes. While a person believes that things will get better in the future, emotional pain can be tolerated. But if no improvement is expected, despair ensues and the likelihood of self-destruction escalates.

It has long been recognized that high levels of hopelessness are associated with a greater risk of suicide. But what underpins hopelessness? Is it the anticipation that lots of negative events are imminent? Or is it the perception that nothing positive will happen in the future? Or is it a bit of both? Research has shown that hopelessness is synonymous with a lack of positive anticipation.

Social deprivation and economic adversity may contribute to an objective perception of a future devoid of positive experiences. But for many people who feel hopeless about the future the perception is a distorted one that can be rectified by psychological therapy.

Ease of access to means of self-harm will influence the suicide rate

Suicidal states of mind are typically dynamic, the urge to self-destruct fluctuating in intensity. Therefore, the ease of access to potentially lethal means can be a crucial factor in determining whether a person survives.

Trends in suicidal activity support the idea that access to lethal methods influences the suicide rate. Sixty years ago, a common way of committing suicide was to put one’s head in the gas oven. Detoxification of the domestic gas supply in the 1960s and 1970s corresponded to a fall in the suicide rate. Conversely, between 1980 and 2000, the rate of suicide via carbon-monoxide poisoning (from car exhausts) paralleled the increase in motor-vehicle use.

Psychiatric services try to deny suicidal patients access to lethal methods of self-harm by, for example, removing ligature points from psychiatric in-patient wards (to reduce opportunities for hanging) and only prescribing limited amounts of medication at one time (to reduce opportunities of drug-overdose).

People who commit suicide have usually told someone of their intentions

It is a common myth that people who are seriously considering suicide do not express their intentions to anyone. Research has shown that most suicide completers have told a family member, friend or health professional of their suicidal ideas in the months preceding their deaths. It is therefore important to always take expressions of suicide intent seriously.

Despite this inclination to express suicidal ideas, most people who commit suicide have never been in contact with psychiatric services.

The risk of suicide can increase when someone's mental state is improving

Paradoxically, the risk of suicide for a person with mental health problems can rise as mental state improves. For example, a severely depressed patient might have insufficient motivation or clarity of thought to carry out a suicidal act, and it might be at the point when mood is improving that suicide risk peaks. Similarly, a floridly psychotic patient might be at increased risk of suicide when insight returns and he is able to gauge the detrimental impact of a mental disorder on career and relationships.

The presence of protective factors can lessen the risk of suicide

When a person is feeling desperate, and considering suicide, there may be protective factors that give a person reasons for living. A common protective factor is the presence of children, the suicidal person not wishing to inflict the trauma of suicide on their surviving offspring. Another disincentive might be a religious doctrine that views suicide as a sin, the person contemplating suicide being fearful about what awaits in the afterlife should he deliberately take his own life.