Classism and Credulity in "The Currency Lass"

The Currency Lass

The Currency Lass or My native Girl: a musical play in two acts was written by Edward Geoghegan in the Nineteenth Century. It utilises humour, music and dance to investigate issues of identity that a modern audience might find surprising because the Australian nation has grown larger and become more culturally varied.

The play combines drawing-room comedy (later made immensely popular by Oscar Wilde), with the song and dance of the music hall to create a commercially viable product with a great deal of visual appeal. It was also one of the few Australian plays which the Nineteenth Century censors approved for production on the stage (Williams 1983:30-32).

First Performed in 1844

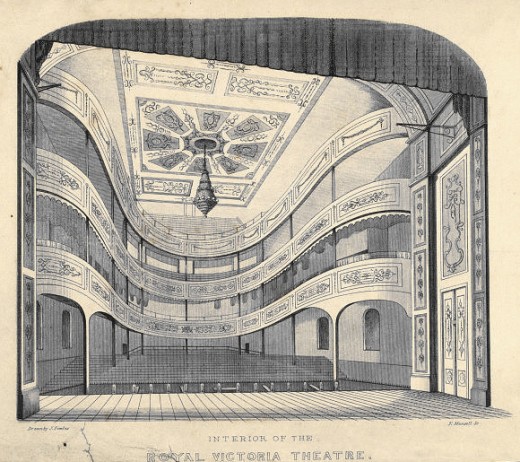

The Currency Lass was first performed in 1844 at the Royal Victoria Theatre located in Pitt Street, Sydney (Geoghegan 1976:xxiii, xxi.). Its action is set in early Sydney Town (p.2), where colonial Australia was attempting to establish it's credentials as an extension of English society, and features references to entertainments such as the “Homebush Races” and recreational cruises “to the Heads" which function as substitutes for London's social events (p. 5).

Plot

When young Edward Stanford writes to his uncle announcing he has developed a romantic affection for "native lass" Susan Hearty, the Uncle Samuel Simile reacts with predictable prejudice.

Not only is this a match not of his own choosing, the young lady involved may be dark skinned! He sets sail for Australia to prevent this disaster and promote a much more suitable match between Edward and young Catherine Dormer.

Susan Hearty is "native" to Australia, because she was born in the country but she is not an Indigenous Aboriginal girl as Samuel Simile assumes.

A major theme of the play is the formation of an identity for “currency” or second generation settlers (Geoghan p.xiii); and this can be translated into modern day dilemmas experienced by many countries regarding the equality of citizens who may be Indigenous peoples, descended from colonists, or newly migrated from a range of countries throughout the world.

The young people play a series of musical pranks upon poor Simile. As Simile loves the theatre, he warms to Susan Hearty because of her acting talent, and the young people pair up in the fashion they prefer, with Catherine Dormer choosing Susan's Brother Harry as her beau.

Heroine

Susan Hearty is described by her lover, Stanford as “sweet, lovely, amiable and intelligent” (Geoghegan 1976:12) and her brother, Harry praises her “sense and candour” (p.16).

Susan admits to having “an honest and confiding heart” (p.20) and takes pride in omitting the fashionable “coquetry” which allows a female to “keep a lover in suspense” (p.16). She is not intimidated when a difficulty such as lack of approval from the Uncle arises, and develops a plan to overcome the obstacle (p.26).

Critics believe the character of Susan Hearty in The Currency Lass was designed to create “an opportunity for a virtuoso performance” by a talented actress who could sing and dance (p.xix). On top of the role of a young gentlewoman, the actress gets to dress up as Frank Foretop the young sailor (p.35) and Mademoiselle Bellejambe the dancer (p.45) whose costume was to reflect that of la Sylphide. The final masquerade the actress playing Susan gets to perform is the role of Charles Clackit (pp.56-62). It may be argued that the prominence given to the actress by her roles in the plays-within-the-play was progressive for the Nineteenth Century theatre.

However this liberation from female gender stereotyping is undercut by the consideration that it may have been more socially acceptable for the Currency Lass to establish the Australian pedigree by being paraded around like a piece of live-stock, than it would have been for her brother the Currency Lad to undergo the same scrutiny.

Wisdom from the mouths of servants

The character of the male servant Lantry would provide the greatest satisfaction to act, as this character provides much of the comedy and a great deal of social commentary through his “chorus-like” interjections. Moreover much of the success of the plays-within-the-play depend upon Lantry delivering letters, introducing Susan in her different persona, providing conspiratorial dialogue for some of Susan's lines, and mocking Simile between each visit.

Another reason why the part of Lantry is rewarding is that this character is relatively free of the racism embedded in the play. Lantry is already marginalised, as a servant and as an Irishman and never gives voices to the unflattering physical description of an Indigenous woman quoted by Stanford and repeated by Susan (p.26).

The traditional view suggests Lantry was created to “differentiate between Irishmen and the Australian” (Kiernander 2009:12), but I see much more in this character. Lantry is the clowning servant in the tradition of Shakespeare's Lancelot Gobbo (Merchant of Venice) or the “devil-porter” of Macbeth (Act II Scene II). Lantry is from the serving class, and yet at the end, is able to demonstrate the democracy of this new country by proposing to marry Jenny and “raise a few young natives to be a credit” (p.67).

Lantry is able to make fun with of the genteel characters position in a changing society. When Stanford berates Lantry for not being available to help him dress, Lantry replies “Well, and who's hindering you?” (p.9) highlighting the fact that a grown man in Australia should be able to dress himself.

The official romantic interest is between Stanford and Susan, and Harry and Catherine, and this does afford some good comic one-liners. For example, Simile asks Stanford whether he has been to see Miss Dormer and Stanford replies “Not yet Sir – the lady was engaged when I called.” (p.32) However, the most unexpected and dramatically sexual romance is between Jenny and Lantry. Lantry is the most audacious lover in the play when he turns the concerns of their employers to his benefit. Susan says Jenny must “instruct” Lantry and the servants are to “lay their heads together” to make a plan to help. Whereupon Lantry kisses Jenny and says “Why, my dear, to obey your misthress' orders to be sure”. (Pp.28-29)

Class-ism and racism

The script utilises verbal wit and features a plot turning upon interpretation of the term “native girl” (Geoghegan 1976:25). The play utilises this device to combat the “slighting attitude” (p.xiii) of Europeans towards Australian born children of white settlers, and sets out to prove their culture and “talent” (p.26).

The only drawback to this comic device is it's inherent racism, as attitudes and values typical of that era are displayed and some comments regarding Indigenous Australians are derogatory.

It is worth noting that the “Native girl” is vindicated before being introduced to Simile as the European complexioned Susan Hearty (p.65), implying grudging acceptance of the character whatever her complexion.

Setting

In The Currency Lass, the environment is bright, comfortable and happy. Harry is overjoyed upon his return home and heaps praises upon “the placid waters of Port Jackson” (Geoghegan 1976:10), “pure” skies, “lovely” girls and “blunt sincerity” of the Australian people (p.11). He has just toured Europe, but declares that the Australian the “sun rose with a radiance to the northern climes unknown” (p.11). Many nautical references throughout the play, including those made by “Charles Clackit” and “Frank Foretop” remind the reader that Sydney is in fact a sea port, with attractions such as “turf”, “regattas”, “theatres” and “dinners” (p.59).

References

Geoghegan, E. 1976 The Currency Lass, or My native Girl: a musical play in two acts, (Ed. Covell, Roger) Currency press, Sydney, (Out of copyright and accessed from e-reserve)

Kiernander, A. 2009 THEA 317 Week 2: 19th Century Australian Theatre, University of New England, Armidale, N.S.W.

McCredie, A. (Ed.) 1988 From Colonel Light into the Footlights: the performing arts in South Australia from 1836 to the present, Page Books PTY. Ltd. Adelaide

Malone, J. 1987 The Penguin Bicentennial History of Australia, Penguin Books Australia KTD., Ringwood, Victoria

Williams, M. 1983 Australia on the Popular Stage 1829-1929: a historical entertainment in six acts, Oxford University Press, Melbourne