A Freewheelin' Time: A Look at Bob Dylan and Consensus Politics

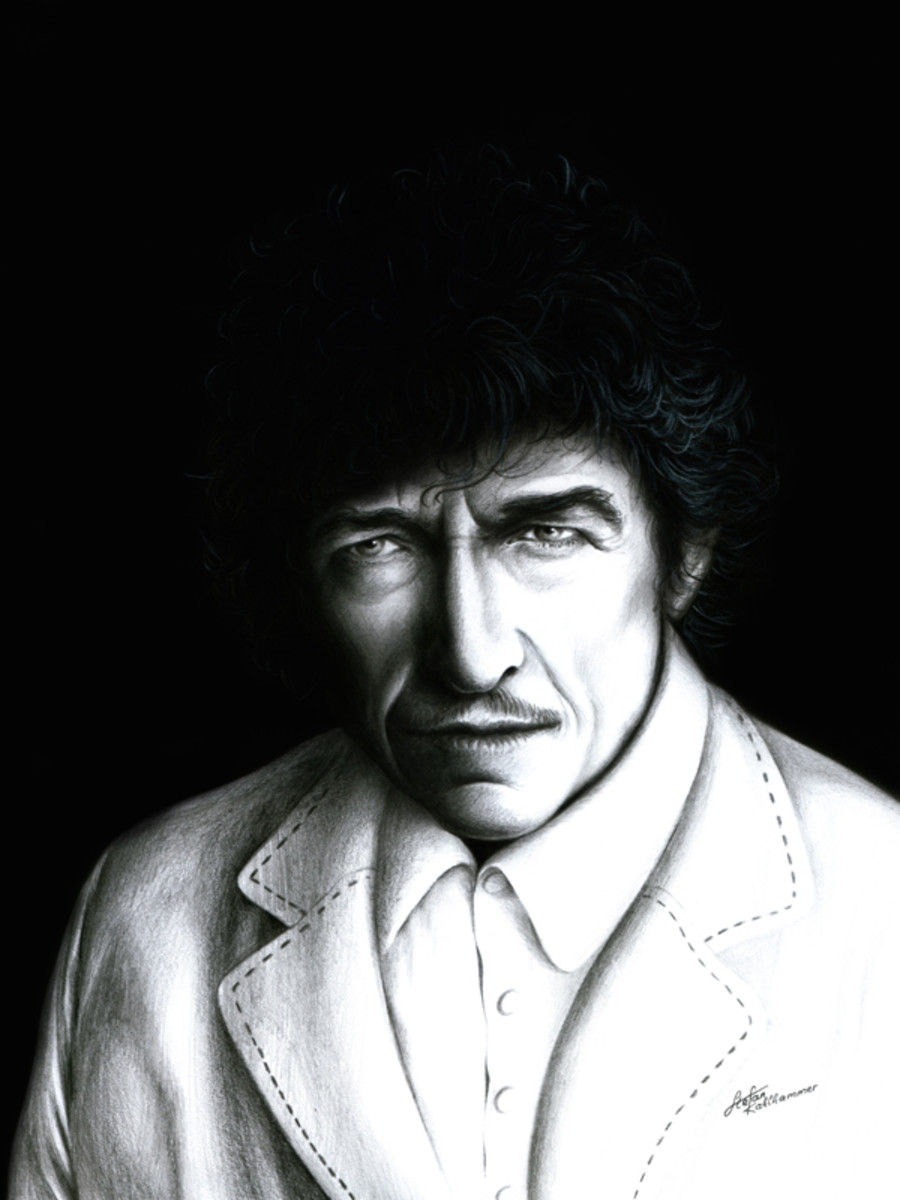

“Dylan could well become this generation's James Dean…But unlike Dean, Dylan is a rebel with a cause” (Aarons-G1).

______________________________

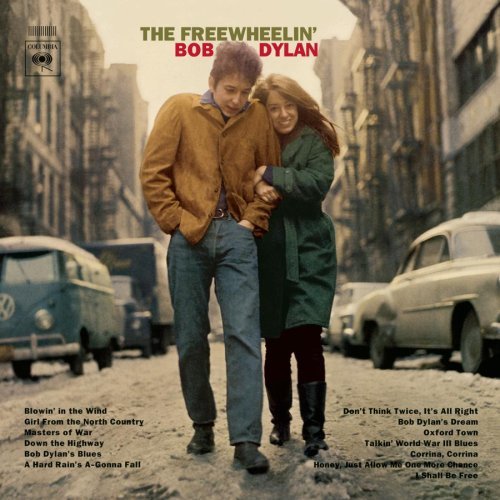

On May 27th, 1963, folk singer Bob Dylan released his second album (albeit his first comprised of all original songs), The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Containing songs regarding the Civil Rights movement (Blowin’ in the Wind) and Cold War politics (Masters of War), the album itself dealt heavily with 1950s consensus politics (which stressed social order and military action to defeat Communism). Thus, in dispensing controversial ideas aimed at the critical analysis of consensus politics, the album itself is a reflection and therefore product of such politics, both lyrically and through songs that were deemed too controversial against the backdrop of the consensus, and were thus dropped from the album (The Death of Emmett Till, Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues). As a historical text, the album, in pushing controversial topics, laid the groundwork for the folk music revival as a tool of the Free Speech movement by making said topics more mainstream and thus accepted. Furthermore, as an early piece of the folk music revival, the album, in being aimed at Civil Rights and often being performed at Civil Rights rallies, exhibits the idea that folk, as a political tool, was not original to the Free Speech movement, but was re-appropriated from the Civil Rights movement by the Free Speech Movement (just as ways of organizing, ideals, and tactics had been).

To begin an analysis of an album produced against the backdrop of 1950s consensus politics, perhaps it is best to fully iterate what consensus politics truly were. At the end of the destruction caused by World War II, economic markets all over the world lay in ruin and were waiting to be dominated by the increasing consumerist production of the United States. Coupled with the rise of the Soviet Union as a world superpower (and as the antithesis to U.S. consumerism), a type of politics began to rise, controlling both political and everyday life in the U.S. This type of political climate ultimately existed to ensure America would continue its economic prosperity and dominance as a world superpower. Within consensus politics, four key traits existed which created a roadmap of sorts for Americans to live their lives: one, confidence in U.S. capitalism, two, gradual social reform will occur from economic growth, three, class conflict is destructive, and four, social unity is the key to defeating communism and ensuring America’s dominance. Thus, consensus politics existed as a means to keep social justice and equality at a minimum and conformity at maximum. Following John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, however, an air of change began to permeate the social order of the nation.

While Kennedy was an ardent proponent of consensus politics, his age, ethnic-background, and certain policies inspired a movement among the nation’s youth, to in effect, push back against the consensus politics to which they were raised. Nowhere is this idea more profound than in songs found on Bob Dylan’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. The album’s title itself, Freewheelin’, implies a sense of a free movement of ideas against a conformist world; the album’s cover, a low angle shot of Dylan with his hands in his pockets walking the streets of New York, evokes memories of a similar famous picture of James Dean (Schatt-Untitled), the original rebel of consensus politics (many contemporary reviews called Dylan the new Dean (Aarons-G1, Shelton-22)). The song that opens the album ultimately retains a concealed attack on consensus politics, in preparation for the rest of the album.

One of the better-known songs on the album, Blowin’ in the Wind is not an overt protest song. Nevertheless, the song pokes and prods at the idea of consensus politics through small, vague lyrics. The second stanza contains lines like, “Yes, ‘n’ how many years can some people exist, Before they’re allowed to be free?” and “Yes, ‘n’ how many times can a man turn his head, Pretending he just doesn’t see?” (Dylan).Thus, the song contains references to the idea, that under consensus politics, certain peoples “exist” not being “allowed to be free.” In this way, Dylan is referencing the Civil Rights movement, fighting not for gradual change under consensus politics, but for speedy equality. Furthermore, Dylan is asking audiences (most surely white teenagers) to not sit by and watch the injustices created by consensus politics.

By not mentioning specific groups or names in the song, Dylan is effectively shrouding his attack on consensus politics. This is vital, as it allows, in effect, an anti-establishment message to be played around the country and be accepted in the mainstream, even to the point, as one contemporary newspaper writer notes, the song was “chanted with ingenuous fervor by Southern schoolboys” who had missed “[the song’s] anti-racist message” (Aarons-G8). Even numerous mainstream magazines published, not the entire song, but only the second verse and its attack on the consensus (TIME - 5/31 & 6/19, 1963).

Thus, with Blowin’ in the Wind, Dylan effectively sings an attack on consensus politics, and how it effectively stunts the civil rights and equality. Furthermore, the song calls for listeners to join in the Civil Rights movement. The song’s importance, however, lies in its discreetness, which allows an attack on consensus politics to reach the ears of those who support consensus politics. Another song on the album, however, is not so discreet.

In the song Masters of War, Dylan continues his attack on consensus politics. This song, however, more openly attacks the foreign and military policies of a government run by consensus politics, as well as the idea that America can dominate the world for simple riches. In the song, Dylan begins:

“Come you masters of war

You that build all the guns

You that build the death planes

You that build the big bombs

You that hide behind walls

You that hide behind desks”

(Dylan)

Amid President Kennedy’s numerous consensus policies was the idea of counterinsurgency. Using clandestine Special Forces groups, such as the Green Berets, Kennedy hoped to spread American ideals and dominance using the military. Dylan’s intro of the song is effectively identifying politicians like Kennedy as proponents of the consensus (the “masters of war”), who “build all the guns” and use the Green Berets to spread consensus politics across the globe.

Most importantly, the song’s final verse raises the question as to why consensus politics exist, as well as if such conformity is worth it. Talking directly to the “masters of war,” Dylan asks, “Is your money that good, Will it buy you forgiveness, Do you think that it could. I think you will find, When you death takes its toll, All the money you made, Will never buy back your soul” (Dylan). Thus, the song effectively argues that the cause of consensus politics, economic prosperity, is not worth the death and injustice such prosperity will bring. One review of the song, however, concretely relates such doomed consensus foreign policy with the injustice it breeds at home.

In LIFE Magazine, reviewer Chris Weller writes of thesong,that Bob Dylan’s “villains are the people he calls the ‘Masters of War’…the hypocrites who claim that ‘with God on our side’ they can justify whatever evil they want to commit: the professional anti-Communists; the segregationists” (Weller – 115). Hence, this contemporary writer demonstrates that the ills Dylan writes of on the album, whether it is civil rights injustices or hapless conformity, can be traced back to consensus politics. This reviewer also mentions another song, a more focused song on the ill-hearted effects of consensus politics that is nowhere to be found on the album.

Written about the 1955 murder of a young African-American boy (and the innocent verdict bestowed upon the white suspects), The Death of Emmett Till was written and recorded during the recording sessions for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (Heylin-15). But why was the song not included on the album? Ultimately, the answer lies in its forward attack on consensus ideology.

With lyrics like, “Then they rolled his body down a gulf amidst a bloody red rain, and they threw him in the waters wide to cease his screaming pain, The reason that they killed him there, and I’m sure it ain’t no lie, Was just for the fun of killin’ him and to watch him slowly die” (Dylan). Dylan is not afraid to describe the brutal effects of consensus politics. Calling the trial a “mockery” and adding that “nobody seemed to mind,” Dylan concludes the song believing, “If you can’t speak out against this kind of thing, a crime that’s so unjust, your eyes are filled with dead men’s dirt, your mind is filled with dust…For you let this human race fall down so God-awful low!” Hence, Dylan is arguing against the conformity perpetuated by consensus politics; a conformity that does not allow racial justice to be served, and conformity that claims that racial conflict and talk of racial justice is the downfall of the country.

The song’s forwardness, however, was not like that of Blowin’ in the Wind; its attack on the consensus was too blatant. While Blowin’ in the Wind hid its messages well, The Death of Emmett Till, was too open, and was played only at concerts around the time of the album’s release. Another song left off the album, however, drew even more controversy.

Founded in 1958 by anti-communist extremists, the John Birch Society was an organization endowed with paranoia and fear over conspiracy theories, relating to a socialist run U.S. government (Lytle-88) – an organization practically synonymous with consensus politics. In Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues, Dylan weaves a comical tale that trivializes the anti-communist ideology of consensus politics.

Written from the point of view of a member of the John Birch Society, Dylan sings, “Now we [the members of the John Birch Society] all agree with Hitler’s views, Although he killed six million Jews, It don’t matter too much that he was a Fascist, At least you can’t say he was a Communist! That’s to say like if you got a cold you take a shot of malaria”(Dylan). In a comical punch at the Society, Dylan exclaims, “Well, I quit my job so I could work all alone, Then I changed my name to Sherlock Holmes, Followed some clues from my detective bag, And discovered they was red stripes on the American flag!” (Dylan). In perhaps his most direct attack on consensus politics, Dylan exhorts the idea that in its quest to defeat communism, consensus politics would push the country to the brink of fascist Germany, and the red stripes (akin to civil liberties) would have to be removed from the flag. Thus, it is easy to see why the song, in its forwardness, caused so much controversy. This is evident in a conflict that occurred weeks before the albums release.

On May 16th, 1963, as Dylan was scheduled to appear on the popular Ed Sullivan Show, CBS officials exerted pressure on Dylan not to play Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues (Adams-61). Known for its middle-class respectability, The Ed Sullivan Show could not allow such a blatant attack on mainstream political and domestic ideology, and Dylan eventually walked off and did not appear on the show.

As Dylan later explained in The Village Voice, "...other John Birch songs, you can listen to the beat or the music or something. But mine, you've got to listen to the words. That's what I wanted the people to hear” (Hentoff-4). As Suze Rotolo, girlfriend of Dylan at the time, notes in her memoir, Dylan couldn’t play a show in which consensus politics and McCarthy-era political censorship existed (Rotolo-219). Rotolo further notes that after the Sullivan Show fiasco, Columbia Records was not going to release Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues (Rotolo). As the event shows, the song was a straightforward, inflammatory attack on consensus politics - an attack too strong to see the light of day.

As one can see, Dylan’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan contained (and would have contained) songs, which were inherently shaped by, and offered critiques of, consensus politics. From simply hearing the songs, one can learn of what consensus politics truly were, and how sharply it defined the landscape of the time. But in pushing back against the consensus, what effects can The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan be said to have on listeners of the time?

Ultimately, the songs on the album overwhelmingly make listeners take notice of the political backdrop which defined their world at the time. But, in making listeners aware of the over-arching ideology that shapes their world, Dylan also argues solutions to softening such conformity.

In Blowin’ in the Wind, Dylan makes the audience aware of people who aren’t “allowed to be free,” and those who sit by and “turn” their “heads;” But, he also offers a solution – “The answer is blowin’ in the wind” (Dylan). While the song does not give a clear-cut solution, it never the less dispenses hope and the idea that listeners can themselves take action and find the answer. As Dylan proclaims in the liner notes of the album, “The first way to answer these questions in the song is by asking them. But lots of people have to first find the wind” (Hentoff-Album reverse).

The same is true in Masters of War. The song ends with the lines, “And I hope that you die, And your death’ll come soon…And I’ll stand o’er your grave, ‘Til I’m sure that you’re dead” (Dylan). Revealing the mortality of politicians, the song shows that those in power do not hold all the answers. Hence, the album not only makes listeners aware of consensus politics, but also leads listeners down a path of free will and choice. Along with other such media of the time, the album effectively lays the bricks in the road that many students would eventually take in forming the Free Speech Movement, allowing views opposed to consensus politics to flourish.

The idea that this album laid the groundwork for the Free Speech Movement, and the Folk Music Revival within this movement, raises questions in that many of the songs found on this album deal with civil rights. With the Free Speech Movement occurring in 1964, and folk being used as a type of rallying sound for the movement, how does a folk album released in mid-1963, dealing heavily with civil rights, fit into the context of the Free Speech Movement and the Folk music revival?

As The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan suggests, folk music in the early 1960s was not strictly geared towards the mobilization of youth culture having their own voice as a group; rather, folk more intently dealt with the Civil Rights movement. Shortly after The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released, the singer travelled south in order to sing his new album at various civil rights rallies. As one New York Times writer noted, Blowin’ in the Wind was one of the most “artistic, and certainly the most popular” so-called “’Northern Freedom Songs’”(Shelton-7). Another article notes that there have been “many echoes in the North of the freedom songs among white and Negro singers,” including “’The Ballad of Emmett Till,’ about a slaying in Mississippi, and ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’” (Shelton-1). As it can be seen, folk, in the time before the Folk Music Revival, was essentially geared mostly towards the Civil Rights Movement.

And while it has been said that folk music was simply the white replacement of church singing and gospel music in the Free Speech Movement, it can be unquestionably said that folk music was first seen as a type of “Northern Freedom Song” (Shelton). Hence, in viewing folk in relation to the Free Speech Movement, it can be said that folk music was adopted from the Civil Rights Movement. This is not dissimilar to how strategies of protest, organization, and tactics were also adopted from Civil Rights groups. In a sense, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, with songs first used in the Civil Rights Movement, exhibits how closely related organizations like C.O.R.E and S.N.C.C. were to the Free Speech Movement, as the type of music (folk) permeated between the two.

In the end, the album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan retains songs which were written in the foreground of a world with a background deep in consensus politics. The album’s many songs, such as Blowin’ in the Wind, Masters of War, The Death of Emmett Till, and Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues make the audience fully aware of the existence of consensus politics. At the same time, by critiquing consensus politics and its inherent conformity, the songs show that that particular form of living has its flaws and is not the only choice. In discussing topics counter to the consensus, the album essentially lays the groundwork for youth, as a group, to begin the Free Speech Movement. At the same time, the album shows that it’s roots lie also in bringing attention to the Civil Rights Movement (also a group existing counter to consensus politics). In this way, the revival of folk did not have its roots in the Free Speech Movement, but in civil rights. As a tool of both movements, folk, and this album especially, thus show how truly related the Free Speech Movement and the Civil Rights Movements were, both as movements existing counter to consensus politics.

Matthew Gordon is the author of The Thin Blue Line: An In-Depth Look at the Policing Practices of the Los Angeles Police Department &

To Live, To Think, To Hope - Inspirational Quotes by Helen Keller.

© Matthew Gordon, 2011

Other Works By The Author:

NOTES

* * Primary Sources * *

Aarons, Leroy F. "Fresh Voice Rising in Folk Wilderness." The Washington Post. 8th August

1963. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdwebdid=185867332&sid=1&Fmt=2&cli entId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Aarons, Leroy F. "Topical Songwriting Tops City Folk Wave." The Washington Post. 24th

November 1963. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdweb?did=185889472&sid=2&Fmt=2&c lientId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Adams, Val. "Satire on Birch Society Barred From Ed Sullivan's TV Show." The New York

Times. 14th May 1963. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10.<http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdweb?did=90557236&sid=5&Fmt=2&clientId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Dylan, Bob. "Blowin' in the Wind Lyrics." Bobdylan.com. Accessed 10.14.10.

<http://www.bobdylan.com/#/songs/blowin-in-the-windl>.

Dylan, Bob. "The Death of Emmett Till Lyrics." Bobdylan.com. Accessed 10.14.10.

<http://www.bobdylan.com/#/songs/the-death-of-emmett-till>.

Dylan, Bob. "Masters of War Lyrics." Bobdylan.com. Accessed 10.14.10.

<http://www.bobdylan.com/#/songs/masters-of-war>.

Dylan, Bob. "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues Lyrics." Bobdylan.com. Accessed 10.14.10.

<http://www.bobdylan.com/#/songs/talkin-john-birch-paranoid-blues>.

Hentoff, Nat. "Freewheelin' Bob Dylan Liner Notes." The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. 27th May 1963.

Hentoff, Nat. "Dylan Skips CBS Over Birch Talk." The Village Voice. 16th May 1963: 4. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=KEtq3P1Vf8oC&dat=19630516&printsec=frontpage>.

Rotolo, Suze. "A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties." New York: Broadway Books, 2008.

Schatt, Roy. "Untitled Photo of James Dean." 1954. Photography. <http://www.baranyartists.com/royschatt/james_2_7.html>.

Shelton, Robert. "Songs a Weapon in Rights Battle." The New York Times. 20th August 1962. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdweb?did=90178256&sid=7&Fmt=2&cli entId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Shelton, Robert. "'Freedom Songs' Sweep North." The New York Times. 6th July 1963. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdweb?did=82074157&sid=6&Fmt=2&cli entId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Shelton, Robert. "Folk Songs Draw Carnegie Cheers." The New York Times. 28th October 1963. ProQuest Historical Newspapers Database. Web. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://proquest.umi.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/pqdweb?did=80476517&sid=3&Fmt=2&cli entId=51903&RQT=309&VName=HNP>.

Weller, Chris. "The Angry Young Folk Singer." LIFE Magazine. 10th April 1964: 109-115. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://books.google.com/books?id=D0gEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA108&dq=bob+dylan&hl= en&ei=uVPfTNj6BYaBlAfgoN2ZAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved =0CEYQ6AEwBzgo#v=onepage&q=bob%20dylan&f=false>.

Unknown. "Folk Singers: Let Us Now Praise Little Men." Time Magazine. 31st May 1963. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,896825- 1,00.html>.

Unknown. "Folk Music: They Hear America Singing." Time Magazine. 19th July 1963. Accessed 10.14.10. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,896904,00.html>.

* * Secondary Sources * *

Heylin, Clinton. "Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions, 1960-1994." New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Lytle, Mark Hamilton. "America's Uncivil Wars." New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.