Classical music: the birth of an idea

Classical music can mean a lot of different things. At its narrowest, it refers to music written mostly by Viennese composers (especially Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and, according to some enumerations, Schubert) between about 1750 and 1830. The so-called Classical Period comes between the Baroque and Romantic Periods.

At its broadest, classical music can best be described as the kind of music played on classical music radio stations, but then it includes such things as Rossini operas, Strauss waltzes, Sousa marches, and even Broadway musicals--music that was not considered classical music at the time it was composed.

So where did the idea of classical music come from? Did composers of the Classical Period consider that they were writing classical music? And at whatever time there is something called classical music, what other kinds of music are there?

To answer these questions, it is necessary to look not at any style characteristics of the music of different times, but at the broader social, political, and economic climate in which it first appeared.

Before about 1700, a hierarchy of aristocrats ran everything. Kings (and the Holy

Roman Emperor) occupied the top of the hierarchy, but below them, a collection of dukes, archdukes, marquis, counts, earls, margraves, and such filled out the ruling class, which owned all the land and collected taxes, rents, etc.

The vast majority of the population of Europe comprised peasants, who worked the land, but beginning at least in the late Middle Ages, a middle class arose. It included bankers, skilled craftsmen, merchants, and others who were not born to the nobility, but had worked their way out of the peasantry. It was always the goal of the middle class to become as much like the nobility as they could. (The rulers passed sumptuary laws forbidding commoners to wear clothes made of certain fabrics, for example, to maintain the social distance.)

Some Music probably appealed to all segments of society. Other music appealed only to the peasantry, and hardly anyone else took notice of it. It survives, if at all, as folk music.

The aristocracy, with its ability to hire the best available musicians, commissioned works by the composers that are familiar to anyone who has ever taken a music appreciation or music history course. (The middle classes appear not to have had their own music. They listened both to the music available in towns and cities and whatever aristocratic music they could get access to, often a generation or so after the aristocrats had moved on to something novel.)

Socially and politically, the aristocracy had at least two needs that their musical household had to satisfy. They had to appear prosperous and powerful to their own populace. To that end they hired trumpeters and bands of other loud instruments to play, among other things, fanfares and music familiar to the masses whenever they made a triumphant entry into one of their cities.

They also had to impress allies and rivals with lavish banquets and other entertainments, which only invited guests from the ruling classes ever got to hear. Those who genuinely liked music listened to similar music for their own private enjoyment.

This music populates all the modern textbooks. Classical music stations play it--some frequently, others only occasionally--and recordings can be found in the classical music sections of brick and mortar or online stores. But it has nothing to do with the idea of classical music.

These aristocrats wanted a constant stream of new music written for them. Music written for special occasions like weddings, baptisms, or funerals was very likely never heard again. With some notable exceptions, once a composer died, performances of his music ceased not long afterward.

The education of the nobility had always included music, and they always considered themselves men and women of leisure. They had always been able to enjoy music that was technically difficult to play and sophisticated in construction.

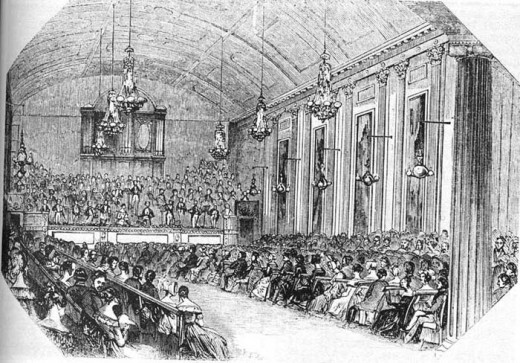

The turning point came around the middle of the eighteenth century, when the middle class had grown in numbers and power. They had money and leisure to spend on opera, concerts, and learning to sing and play instruments for their own entertainment, but not enough to acquire the same level of music education as the nobility.

What the middle class wanted, and could afford, was music that was easy to listen to, relatively simple in structure, and required less than professional proficiency to perform it. By the 1780s, the nobility adopted the same music as their own. Now, for the first time, instead of the middle class imitating the tastes of the nobility, the nobility began to copy the middle class.

Although the music of the first generation of composers in this new, simpler style (including Giovanni Battista Sammartini), like most earlier music, stopped being performed shortly after they died, Joseph Haydn gave it a new polish and sophistication that ultimately had a world-wide appeal, across all class boundaries.

Haydn worked for the Esterházy family nearly all of his career. His first contract, typical of contracts for composers serving noble households of the time, specified that he compose whatever music the prince demanded and not allow anyone to copy it for use elsewhere.

After the prince that wrote the contract died, Prince Nikolaus considered it advantageous to have a well-known music director. Under Nikolaus, Haydn accepted commissions not only locally, but from Paris and Spain. Both through printed music and manuscript music, his music became know and loved all over the Holy Roman Empire, and from there west to the British colonies in America and from Italy all the way north to Sweden. Mozart and Beethoven's popularity covered a scarcely smaller area.

The French Revolution and its aftermath ended public concerts in Paris for nearly thirty years. Concert life barely survived much past the turn of the century in the other two major European cultural capitals, London and Vienna. These same cities were also the major centers for music printing. With no concerts, publishers had no market for concert music. They switched to the less expensive and more lucrative market for popular songs.

When Beethoven and Schubert died (1827 and 1828 respectively), the Classical Period ended. They had no followers. That is, no living composers truly appealed to the audience for symphonic music that valued it more for its artistic merit than for its entertainment value.

Meanwhile, those who wanted entertainment and cared little for art had plenty of music to choose from, including piano music by composers whose names are now known only to scholars and operas by composers such as Rossini and Meyerbeer.

In the 1830s, after concert life in Paris and London, at least, had resumed, a French critic observed that there were only two kinds of musicians: Rossinists and Classicists.

By that time, the divisions between musical audiences no longer occurred along class lines, as they had throughout most of history. In fact, the upper reaches of the middle class and the aristocracy virtually merged into one upper class by the 1850s. Instead, both middle-class and aristocratic audiences fractured over matters of taste.

Classical music became defined as music that exhibited the artistic values of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. By the end of the 1830s, composers like Berlioz, Mendelssohn, and Schumann emerged and strove to write artistic music, but the core of the repertoire was (and has since remained) dominated by dead composers for the first time in history.

During the lifetimes of the great Viennese classicists, their music did not require painstaking study, because it was current. By the time their music became classical music, it did require study, as well as repeated hearings, in order for its artistic merits to reveal themselves.

"Rossinists," on the other hand, wanted music they could easily grasp at first hearing. They also wanted and needed novelty. Easy listening music soon becomes stale if there is nothing to it beneath the surface. Its audience will necessarily crave new music that is both comfortably familiar and somehow strikingly different. We can call it popular music.

The ideas of classical music and popular music arose at about the same time and for the same reasons. This article has considered only one: the fact that the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars made it economically impossible to sustain the kind of concert life that could have allowed new artistic music along the lines of the great Viennese classicists to keep up to date and retain its entertainment value.