German Cinema: Nazi Films and the Lessons We Can Learn

A Little Clarification

It must be noted that the movies made by the Nazi regime have been, for the most part, relegated to film students and extremists outside of Germany. This is because of the ideological nature of Nazi propaganda and many find it difficult to watch movies knowing the severity of the Reich’s hatred and eventual destruction

I will clarify, however, that most of the movies made during the 1933 to 1945 period were not Nazi propaganda, but were normal dramas, comedies and the like. They couldn’t insult or question the Nazi ideology and all were watched and approved by Josef Goebbels, but of the 1,097 features made during this period, only around 180 films were banned outright by the Allies for having Nazi propaganda.

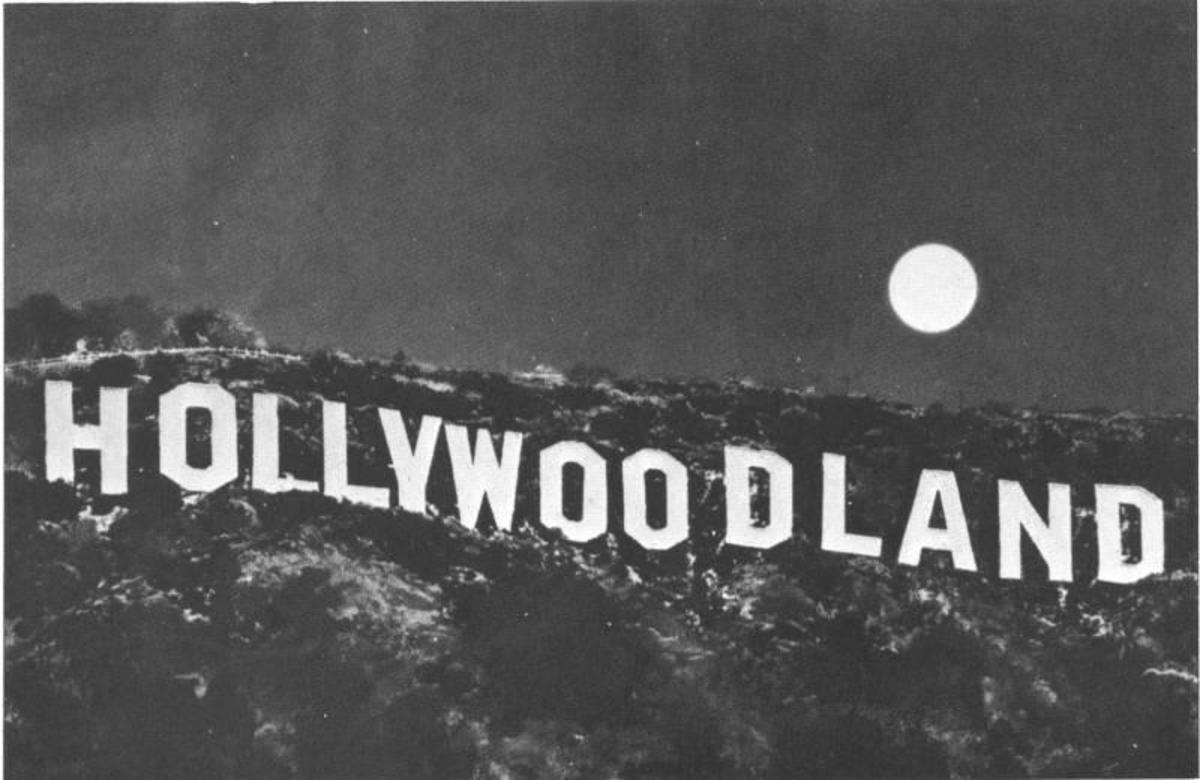

The majority of the other movies of this period didn’t bother to address Nazism directly and these Hollywoodesque films are still being watched as “golden era” films on German television today.

The Reich used Propaganda Early

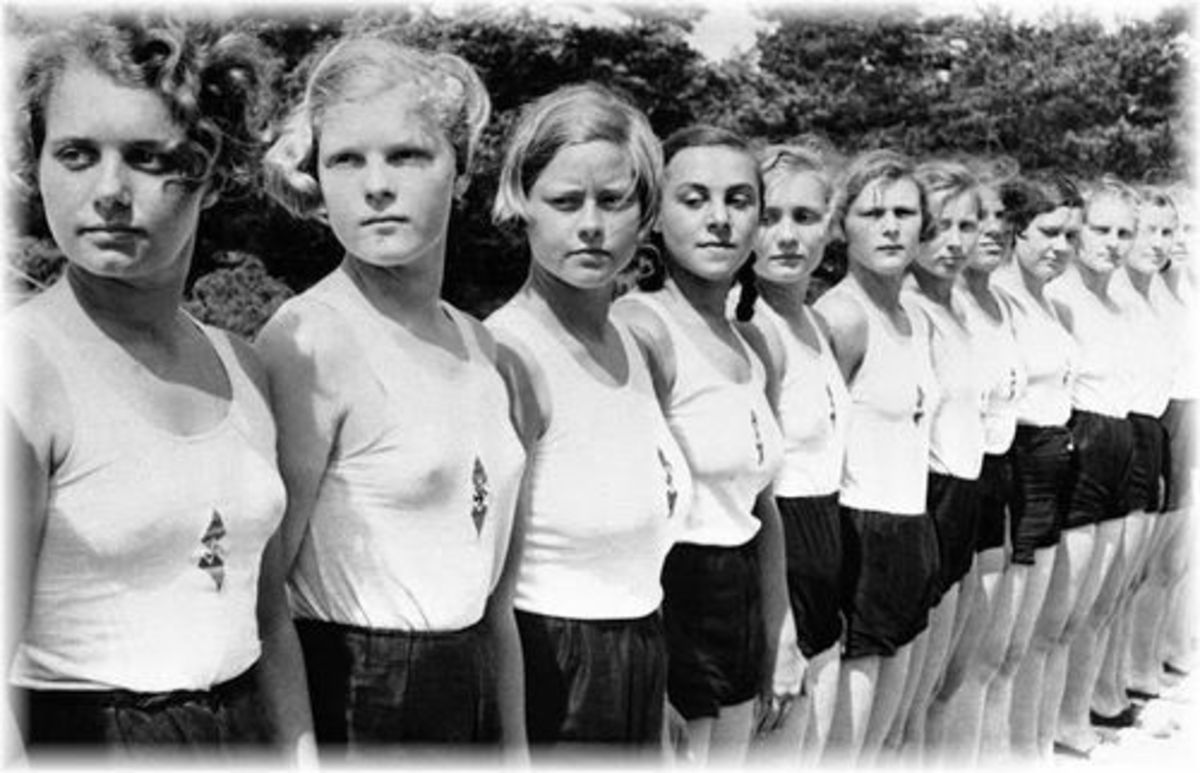

The Nazis used film as a powerful propaganda tool as soon as they took control of German film industry. Films like SA-Mann Bran (Seitz, 1933), Hans Westmar (Wenzler, 1933) and The Quicksilver Hitler Youth (Steinhoff, 1933) were created to glorify Nazis as heroes and to strengthen support amongst the German people. Most of these films took place before the Nazi take over and was meant to show the struggle between the blood thirsty Communists and the brave Hitler supporters.

- Film Review of the Day: The Last Laugh

This is a film review for the silent film The Last Laugh by Murnau. Read about the movie, learn some interesting facts about the actor, director and era then watch a clip to decide for yourself.

She Rose Above them All

Of the many directors of this period, there is one that stood next to Hitler and created two of the most powerful propaganda films to ever be made by any side. Leni Riefenstahl was an actress in the silent era, who turned into a director, making The Blue Light (1932), in which she also stars. She created the movies with Béla Balázs (who wrote It Happened in Europe, 1947) and the brilliant German Empressionist writer, Carl Mayer (who wrote The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Last Laugh). Things changed when the film achieved some success and was re-released in 1938. At that time, Riefenstahl had Balázs and Mayer's names removed from the credits. She said because they didn't have as much to do with the film as she, but the truth was a little easier than that. Not only were both men Jewish, she no longer had to cut her profits with the pair. She was not a woman to be trifled with.

During the making of The Blue Light, Riefenstahl read Mein Kampf and became a National Socialist. She soon met with Hitler who asked her to direct an hour long film on the Nazi party rally at Nuremberg in 1933.

Two Must See Films

Hitler saw something in her ability and asked her to film the 1934 rally at Nuremberg. Riefenstahl agreed, but only with the conditions that she had complete control of what she did and that her next film be one of her choosing. Hitler agreed and at the rally she irritated Goebbels to the point of fury, but created a masterpiece in Triumph of the Will. It succeeded in showing Hitler’s power and resources by highlighting Riefenstahl’s skill with editing, music and cinematography.

Riefenstahl chose her next subject, the Olympic games of 1936 and though she claimed it was not Nazi propaganda, it is, though not as abrasively so as Triumph. In Olympia, she uses her skill set and mass amount of financing from the government. It was meant to show the racial superiority of the Aryan race, instead she focused more on the beauty of the athletes, including American gold medal winner Jesse Owens. Nazi or not, the woman had her own vision and the only rules she followed were her own.

Olympia's Famous Diving Sequence

Enemies, Enemies Everywhere

Of the propaganda films made, there were some purposefully commissioned by Goebbels to be anti-Semitic when Hitler announced his “final solution” in 1939. These enemy films attacked the Jews as being problems, highlighting their stereotypes and condemning their existence.

On one end was Jew Süss (Harlan, 1940), a subtle, yet obvious, lambasting of Jewish greed and violence. It was such a popular film that it incited violent incidents against Jewish people.

On the other was The Eternal Jew (Hippler, 1940) a judgmental documentary that sent out to prove that the very existence of Jewish people was a crime. This movie proved too unpopular since overt anti-Semitism was location based instead of widespread. It also didn’t help that Hitler wanted to deflect attention away from the growing number of concentration camps and the exterminations held within.

It was difficult for Germany to pretend these things weren’t happening when directors shoved them in their face. Instead, Goebbels wanted to focus on promoting the war and glorifying the Nazi’s role in it. He commissioned Kolberg (Harlan, 1945) as a historical epic set during the Napoleonic wars. He had hoped that the movie would inspire ordinary German citizens to rise up and arm themselves, as in the film, to stave off the impending loss of World War II. By the time the movie released, most Berlin cinemas had been bombed out by the Allies and no such Nazi last stand would occur.

The End of the Reich

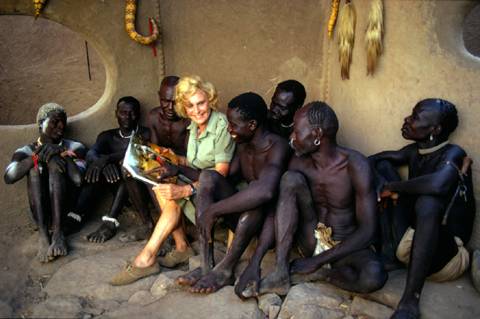

What to do with the filmmakers involved with Nazi films? It was something the Allies had to deal with after Hitler’s demise and Berlin was captured. Josef Goebbels, the head of propaganda, committed suicide when Berlin was overrun. Some directors fled Germany. Leni Riefenstahl returned to her native Austria and though she was investigated and blacklisted until she was cleared on any charges. She began directing again in 1952 (Tiefland in which she also stars) and continued until her death in 2003. During this period, she mainly focused on the beauty found in Africa (taking pictures of the land and people) and undersea (captureing underwater shots), and featuring them in print.

Veit Harlan, who made Jew Süss, was the only filmmaker charged and tried for crimes against humanity. During his trial, he claimed that he and other directors were forced to direct for the Nazis and since there wasn’t enough evidence, he wasn’t convicted.

A Video Highling Riefenstahl's Photos in Africa

Lessons Learned

In the end, most of the films of this era would be largely (and rightfully) ignored by the world. Only a few continue to be watched and examined, both for their excellence in filmmaking and for the lessons that can be learned by watching them.

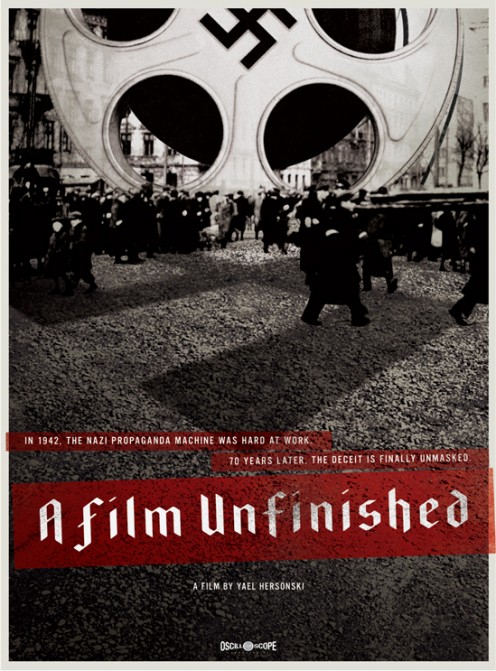

There is another side: the film footage taken by the Germans themselves to show the hideousness of their action. A Film Unfinished (Hersonski, 2010) took footage from a film about the Warsong Ghetto and instead of showing the horror of the Jews, as it was intended; the film magnifies the horrific ways the Jews were treated both in front of and behind the cameras.

If you have never watched any of these films just know that watching them doesn’t mean you are condoning what happened during this horrific period. There are a lot of lessons to learn and by watching a few of the more important films from this period; we can remind ourselves how easy it is to go too far.